THE WHOLE SHEBANG: Preacher Casey, Tom & Ma Joad & the Way of Universal Salvation

James Ishmael Ford

6 May 2012

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

And the angel thrust in his sickle into the earth, and gathered the vine of the earth, and cast it into the great winepress of the wrath of God.

The Book of the Revelation of John the Divine 14:19

These are hard times.

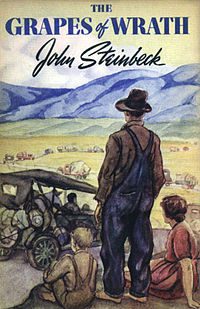

And as I consider them, I find my mind, my heart going back to John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath, what I consider one of the great spiritual texts, certainly one of the most important to be produced on our American soil. And I can’t think of the book without thinking of the movie, and I can’t think of the movie without thinking of the song, of Woody Guthrie’s powerful synopsis.

Like all true stories, there are more than a couple of versions to how Woody Guthrie got around to writing the Ballad of Tom Joad. It appears Woody is responsible for a couple of those versions, himself.

The most likely version seems to be that Woody, who was not famous for wide reading, went one day to a Manhattan theater and saw John Ford’s masterwork, The Grapes of Wrath. He was really impressed, really impressed. He thought it went right to the heart of the matter and was worried that someone without the quarter it cost to see the movie might not get to hear the message.

His friend Pete Seeger recounts how he ran into Woody that very day, and how Woody feverishly asked if Pete had a typewriter he could use. Pete said no, but that his friend Jerry Oberwager did. So, they purchased a half-gallon jug of wine (of course…) and went to Jerry’s apartment, a six-flight walk up.

Pete tells us how Woody, “sat down and started typing away. He would stand up every few seconds and test out a verse on his guitar and sit down and type some more.” Pete added, “About one o’clock (Jerry) and I got so sleepy we couldn’t stay awake. In the morning we found Woody curled up on the floor under the table; the half-gallon of wine was almost empty and the completed ballad was sitting near the typewriter.”

The Grapes of Wrath was very controversial. Some people dismissed the book as some sort of sentimental celebration of the poor. Some so hated the book that it was called, sometimes by the same people, sometimes at the same time a celebration of communism or of Nazism. At the other end I’ve seen people so moved by it that they claimed it was inspired by their religion, Catholic or Protestant, at its best. We do know when the Nobel committee awarded Steinbeck, they cited the Grapes of Wrath as one of their principal reasons.

So, what was it that so caught the imagination of so many people for good and for ill? What made people denounce it, John Ford to make a movie from it just one year after it was published and Woody Guthrie to render it to a song right after that?

I suggest we hear the reason sung to us by Preacher Casey, failed minister, broken heart, witness to all that is, and some of the worst of that up front and ugly. Out of this terrible wound he sang of a great mystery.

“Before I knowed it, I was sayin’ out loud, ‘The hell with it! There ain’t no sin and there ain’t no virtue. There’s just stuff people do. It’s all part of the same thing.’… I says, ‘What’s this call, this sperit?’ An’ I says, ‘It’s love. I love people so much I’m fit to bust, sometimes.’… I figgered, ‘Why do we got to hang it on God or Jesus? Maybe,’ I figgered, ‘maybe it’s all men an’ all women we love; maybe that’s the Holy Sperit-the human sperit-the whole shebang. Maybe all men got one big soul ever’body’s a part of.’ Now I sat there thinkin’ it, an’ all of a suddent-I knew it. I knew it so deep down that it was true, and I still know it.”

Let me confess to you, with variations on it, with a different emphasis here and there, an unwinding of the consequences, this is all I preach.

Here is the universal message of the engaged heart. Each of us is unique and precious. And each of us shares one soul, boundlessness, love. Sometimes we have to pay attention to that part about how precious each of us really are. Sometimes we have to pay attention to how we’re all connected. Most of the hurt we manufacture, the wounds gouged by our human behaviors, come when we forget one truth in favor of the other and act from that one-sidedness.

Now the song of the Grapes is set within a particular hard time in our country when the fact we’re connected, the fact we share one soul was forgotten, ignored, crushed by people who solely following the song of the singular heart were creating wealth for themselves at the cost of using up and throwing away others. And, much of the book was a celebration of the communal response, of smaller expressions of the great unity, particularly revealing the need for unions to balance the accumulation of power in too few hands.

These were dangerous times. And once again we find how we live in dangerous times. I suggest in this country we are haunted by the shadow of a return to those days described in painful detail within that novel, led by preachers of the individual trumping the needs of the community. The callousness of this hidden by twisted philosophies of the individual, either claiming unseen forces at play in the single minded accumulation of wealth that will raise all boats, or more honestly, if brutally, denying we’re related, denying our connections, denying that soul, and with it all responsibility for each other.

There appears to be something in our human hearts, where we pull one way or the other, overbalancing, creating hurt. And so I’m no more fond of philosophies that claim we are all one and ignore the needs and desires of the individual. But, in our country, in these times in particular, that’s not the problem. Far from it. The problem is grasping after wealth at any cost.

So here we are today. I look around me. This is what I see. Today there are those who would throw off the advances of social concern woven into the fabric of our culture for the past hundred years, of intuiting we all share one soul, or, to use another way of pointing to the deeper truth being ignored, of how we are all one family, successfully enough to have half our country today reduced to poverty, maybe half of them desperately poor. Much of this masked by the fact unless one becomes homeless there are refrigerators, phones, televisions and cars. Here one mark of poverty is weight, the poor, most are getting calories, but of the worst sort, leading to an epidemic of diabetes and other similar problems.

But, for those who want to see hunger as the mark of poverty, just wait. If the most radical social policies that are being touted become rule of law, hunger is coming; real stomach burning hunger is just around the corner. Already our food pantries and soup kitchens are running on overtime. Come back here to church any third Monday. Join our loaves and fishes truck going out to parts of the community you may not usually see. There you’ll see what it looks like. And what is spreading, a cancer in this nation.

But, what to do about this? What do I do about this? You? Us?

Well, the book, the film and the song, all address such a time, the soul sickness that allows it, and the cure. For many, and I admit, for me at first, the response is found in Tom Joad’s words. “Whenever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Whenever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there… I’ll be in the way guys yell when they’re mad an’-I’ll be in the way kids laugh when they’re hungry an’ they know supper’s ready. An’ when our folks eat the stuff they raise an’ live in the houses they build-why, I’ll be there.”

And it is true. This is seeing in our own lives everyone else. And acting from that place. Tom is going out to act. All noble, and, frankly, kind of guy-like, part of the appeal to John Ford, whose favorite actor was, after all, John Wayne. There is a hint of gunplay hanging in the air. And, there can be times where that might be the only response. If we’re not careful it can come to that.

When we’re not careful, we simply tumble from one excess to another. Most revolutions end up eating their children. They replace one excess for another. And, frankly, the tyrannies of the communal can be just as awful as the tyrannies of the individual. Look at what happened when idealists won collectivist states, and the horrors that followed for those subject to the power of the certain.

I suggest there’s a third way. We find it in the real hero of the book.

The first time Ma appears it is when Tom tells the preacher an anecdote about her. “I seen her beat the hell out of a tin peddler with a live chicken one time ’cause he give her an argument. She had the chicken in one han’, an’ the ax in the other, about to cut its head off. She aimed to go for that peddler with the ax, but she forgot which hand was which, an’ she takes after him with the chicken.” There’s nothing ethereal about Ma, she lives in a hard world, and she meets it.

And she isn’t foolish. She hears the siren song of the dream California that’s being pitched to the poor and dispossessed. But, she says “‘I’m scared of stuff so nice. I ain’t got faith. I’m scared somepin ain’t so nice about it'” She lives in the real world, and that world has hurt and disappointment as part and parcel.

And, and, and it is Ma who in the camp seeing hunger all around and says we have to feed the children, even when not sure there’s enough for her own. It is Ma at the end of the book, in a scene too hard for the movie, too hard for the song, but which reveals the heart of the matter, who when there is nothing left, nothing, encourages her daughter Rose of Sharon whose baby has been stillborn to breast feed a starving man, the only food left. Hope when there should be none.

In the book we don’t have the closing monologue given Ma in the movie. But throughout she does sing to us. Ma sings the song of hope. Nothing false in her. No pap. Only the real deal. In the book she doesn’t get the fine lines, the words that we remember and quote. I think I prefer that to the speech in the movie. Instead, hers is the way of quiet action, of real action, of reaching out and of leaving no one behind, being fully part of it all, blessing all those who do what needs doing, with love and with care.

Yes, these are hard times.

And many are calling to us with their solutions.

But, if we want the wisest of teachers, of guides through these dangerous times, I suggest, we turn our hearts, our attention, to Ma Joad, who sees the connections, sees the horror and the love at the center of it all, and then gets up and does the work.

We do this, and we may, we just possibly, may find our way through.

Amen.