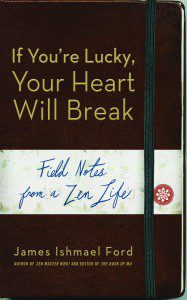

James Ishmael Ford’s

If You’re Lucky Your Heart Will Break: Field Notes from a Zen Life

By Catherine Senghas

This book “had” me already at the title. Perhaps you have heard the oft-quoted story wherein a Zen master holds up a glass and says that he sees this glass as already broken, and thus enjoys it incredibly and appreciates its preciousness all the more. For many this story helps fend off the tendency to put precious things away, to “save” them. If only we looked at our lives in this way—so temporary, so fragile, so essential that they be savored! Ford’s book is his recounting of his experience of Zen Buddhism, that others might be led to discover its relevance for their own lives.

James Ford is both an ordained Soto Zen priest and a Unitarian Universalist minister. As a Zen priest he serves as a guiding teacher of the Boundless Way Zen network of which he is the founding abbot, and as a Unitarian Universalist minister he currently serves a congregation in Providence, Rhode Island. This book is a deep sharing of the meandering through a personal life with continuing pointers to the universal.

In the introduction Ford explains how it was and who he was as he came to Zen, the nature of the institutionalized Zen he came to, and why he continues to engage. Ford describes a personal spiritual journey that has unfurled through an ongoing series of encounters with different teachers and traditions, in much the same way that what he calls Western Zen continues to evolve through encounters of both individuals and traditions.

As he sees it, the future of Western Buddhism is rich and it is getting richer as practitioners reach across the traditional ethnic divides into which the Dharma has arrived in the West and continues to be carried forward. Don’t skip the introduction, so crucial to framing these “field notes.”

The book is divided into three parts. In the first, the author uses koans, traditional Zen teaching stories, interwoven with stories from his own life to illustrate the meaning of and means to “awakening,” a term he prefers to “enlightenment” which has a more singular momentary semantic and perhaps doesn’t fully express the expanded human consciousness already available to anyone willing to commit to this spiritual practice. In this more awakened state, with this liberating shift in consciousness, the individual is far more receptive to the learning possible in each moment—learning about the world, and about oneself. This part of the book captures so well the nature of this shift and the fullness it brings to personal experience. Simply awakening.

The second part reads more like a gentle bouncing between “how-to” and “why” grounded in stories again from Ford’s direct experience as well as from advice he’s received from various teachers about starting a Zen practice. We learn about ways to begin shikantaza practice (“just sitting”) and about koan study, in which Ford is trained in the Harada-Yasutani tradition. Koan study follows a prescribed curriculum under the direct guidance of an authorized teacher, whereby the Zen student explores a series of stories, mostly of encounters between Zen masters or the masters and their students. Each koan has some central insight for the student to realize, which sometimes takes a significant amount of introspection. Ford’s personal anecdotes reveal how varying the different forms of practice and teachers’ styles can be, as well as the importance of attending to one’s personal experience of one’s own practice.

Ford lifts up the importance of finding an authorized and competent teacher; he shares his own story about this quest, which is delightfully engaging. He recommends that if you sense that Zen practice might be right for you that you should read a little bit about it and then start meditating “pretty much right now.” If it really doesn’t feel right to you after six to twelve months, it’s perhaps not worth seeking out a teacher. But if it does feel right, he recommends that you then seek out a teacher, and very carefully. And then he details the steps to take, some pitfalls to beware, and the incredible importance of the sangha as one’s extended learning environment.

In the book’s third part Ford presents an array of areas of our lives that might be ordered by a Zen perspective, and perhaps thereby lived more authentically. He discusses liberal views on the classical Buddhist topics of karma and rebirth, as well as other shifts such as toward more lay practice and the inclusion of women. Ford describes the wrestling of orthodox and classical views with current scholarly analysis, the interface with other religious precepts, and his own personal perspective. It is a rich discussion of contemporary Western Zen, through a personal practical lens. He enumerates moral codes not only Buddhist, but also others, illustrating their universality, and then fleshes out some of the basic Buddhist precepts in their interwoven pragmatic, psychological and spiritual dimensions.

Because I know James Ford personally, as a teacher both in the Zen realm and during a year of my Unitarian Universalist ministerial formation as an intern, I hear his voice as I read this pouring out of observation, advice, and perspective. I hear in it the objective invitation of the Zen teacher—“take it or leave it.” But its form is most useful as both introduction to and revisiting of this spiritual practice that has changed my own life over the last decade. I highly recommend this book to you whether you are beginner or bodhisattva.

I’ll close with the quote Ford uses to open the book, just after the page dedicating the book to his wife Jan. This Zen verse is often chanted as the evening gatha at retreats and hangs on the wall of my own study:

Let me respectfully remind you: Life and death are of supreme importance. Time swiftly passes by and opportunity is lost. Each of us should strive to awaken… awaken! Take heed! Do not squander your life.

The Rev. Catherine Senghas is the Senior Minister and Executive Director at the UU Urban Ministry, Roxbury, Massachusetts, and a member of the Board of the Unitarian Universalist Buddhist Fellowship. This review first appeared in the Summer, 2012 edition of UU Sangha.