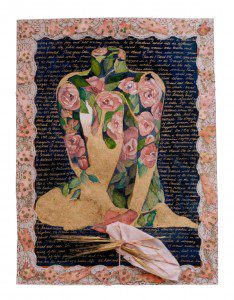

Bread and Roses

A Meditation on the Way of the Wise Heart

James Ishmael Ford

2 September 2012

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

As we come marching, marching in the beauty of the day,

A million darkened kitchens, a thousand mill lofts gray,

Are touched with all the radiance that a sudden sun discloses,

For the people hear us singing: “Bread and roses! Bread and roses!”

As we come marching, marching, we battle too for men,

For they are women’s children, and we mother them again.

Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes;

Hearts starve as well as bodies; give us bread, but give us roses!

As we come marching, marching, unnumbered women dead

Go crying through our singing their ancient cry for bread.

Small art and love and beauty their drudging spirits knew.

Yes, it is bread we fight for — but we fight for roses, too!

As we come marching, marching, we bring the greater days.

The rising of the women means the rising of the race.

No more the drudge and idler — ten that toil where one reposes,

But a sharing of life’s glories: Bread and roses! Bread and roses!

James Oppenheim

Today is Labor Day Sunday. With all the delicious irony of our time and place, today and Monday are times we’ve set aside to relax in honor of labor. Its actual origins are shrouded in the mists of history, although we do know the first state to set a date for Labor Day was Oregon, in 1887, and we know by 1894 when it became a federal holiday, some thirty states already had official celebrations.

It specifically became our national holiday by an act of Congress in the wake of the catastrophic Pullman strike, created as a token of reconciliation, or at the very least in an attempt to blunt public outrage at how the government colluded with Pullman to violently put down the strike. And, again, things are complicated. It is also in part a celebration of the American anti-communist Trade Labor movement, and having this September date for its own, separated it further from the socialist and communist movements which took the 1st of May for their celebrations.

Back to that mysterious truth that things rarely have a single cause, or represent only one thing. So, as such things happen, over the years this holiday has become a marker for things not at all related to questions of labor. It is that last long weekend before summer ends, a time of picnics and for those on the coasts, trips to the beach. For some time it was the last day when the fashionable could wear white, a tradition perhaps sadly today is more alluded to than observed.

For me, however, Labor Day is forever caught up in my imagination with the song Bread and Roses. Originally a poem written by James Oppenheim in 1911, it has been inextricably bound together by the labor action in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912. The poem was set to music by Caroline Kohlsaat (Martha Coleman is sometimes given this credit) and this is the version we sing out of our hymnal. The folksinger and social activist Mimi Farina later recast the poem and that’s the version we’re most likely to hear sung at Labor movement celebrations today.

The 1912 Bread and Roses strike in Lawrence was sparked in the wake of a new law shortening the workweek for women and children from fifty-six hours to fifty-four, when in response an employer reduced the pay of his women and children workers. The reduced wages were calculated as roughly three loaves of bread. giving the strike its other name. Led mostly by immigrant women, the strike spread like wildfire, with more than twenty thousand workers from nearly every Lawrence mill out on the picket line inside of a week. Within the year the strike was crushed, but it would be one of the paving stones leading to the eight-hour workday and the five-day workweek. Something today we’re seeing beginning to fray at the edges. At the time monumental. And even yet, a marker for human dignity.

While probably not a term used by the strikers, that term “bread and roses,” the poem, and the variations on the song would gradually seep into our American souls, reminding us of many things about who we are, and what we need. Obviously the presenting issue is respect for everyone, and certain fundamental rights for people. This is the deep background.

And of course, in something so powerful and complex, there’s more, always there’s more. Layer upon layer for us to explore if we wish. I know I can’t help but find echoes for the deepest strata of what and who we are as human beings and how we might best engage the world revealed in that simple phrase, “bread and roses.”

And it is a metaphor. It is a pointer. And there are others that might help us to delve to the deeper places of what is being pointed to.

As many of you know I’m deeply influenced by the spiritualties of East Asia, particularly the Zen traditions. Thanks to this there are a handful of anthologies of the stories and doings of the great sages of the Zen tradition that have become touchstones for my interior life. And, more; guideposts for how this one precious life I have can best manifest in the world. These days it is a rare event of consequence that I find I’m not enriched by the wisdom presented by those old masters of the authentic life, what I think of as our shared way of the wise heart. So, for instance, when I hear that phrase “bread and roses” I find how I think of the one-hundredth chapter of the twelfth century Chinese classic, the Book of Serenity.

It’s short. “A student of great way asks the master Langya Jiao, ‘The essential world is intrinsically pure and clear. How are mountains, rivers and the great earth at once produced from it?’ The master replied, ‘The essential world is intrinsically pure and clear. How are mountains, rivers and the great earth at once produced from it?’”

Okay, first that line how the essential world is intrinsically pure and clear. For those of us who are familiar with contemporary Unitarian Universalism, this is a pointer to the same intuition we find expressed as “the interdependent web of existence, of which we are all a part.” This is the great whole, wherever thing is included. In our popular culture we might think of the song “Circle of Life” from the Lion King. Yes, that. But more, as well; where everything, absolutely everything has a place and belongs.

Actually the teaching is even more radical, our essence is in fact no essence, we are not bound even within this web that creates and sustains us, wonderful a metaphor that it is, there is in fact a place where there is no web, no circle, each thing we see is in fact a moment, flashing into existence, and in a moment disappearing. We are in fact boundless; we extend beyond all imagining, we, you, me, the whole thing. No boundary.

Walt Whitman sings of this place that we are, this both is and is not, when he asks, “Do I contradict myself?” and when he answers, “Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.” It is critical to understand this quality of interbeing, not just as some abstract truth, but as who we are, really who we are. Much of the spiritual enterprise is about coming to know this truth about us. In the phrase “bread and roses,” I suggest “roses” points to this essential that has no essence, that is the whole web, and is each of us.

Yes, that second part, which is each of us. You may notice in both the phrase “bread and roses” and Langya’s response to the question, there is a second part. Notice how the response to the question put to Langya also comes as a question “How are mountains, rivers and the great earth at once produced from it?” What I particularly love is that question mark. The answer does not conclude with a period or an explanation point. It’s open and dynamic. No boundary, and at the same time, so many boundaries. Contradiction? Yes. So lovely a contradiction. So compelling a contradiction. You. Me. And at the same time, no separation. So, this line from a long dead teacher of the wise heart is an invitation into being, but a being that is all motion. It calls our hands to reach out. It invites our feet to move. Here the whole of that work of justice, which calls so many of us, finds it’s birthing. I believe in “bread and roses,” that “bread” points to what this means.

The Chinese version of the story comes out of a rural setting, and points to what is in front of us. Mountains. And rivers. So lovely. And for many of us, so not us. I think buildings and roads and people bustling about. With “bread,” we are invited into the great mess of life as it is lived. Who grows the wheat? Who harvests it? Who mills it? Who bakes it? Who eats it? The whole of our lived world, with labor and capital, with power and powerlessness, with struggle and rest, with all the things that are creative, and exciting and, oh so dangerous; presented here and now: the great earth.

All presented in the simple phrase, “The essential world is intrinsically pure and clear. How are mountains, rivers and the great earth at once produced from it?” All boiled down and telegraphed to us as “bread and roses.”

So, manifestation is at the heart of it. So, how does it manifest? Well, sometimes by sitting down, shutting up and paying attention, sometimes by a walk on the beach, sometimes when workers and owners sit down across from each other at a table. Sometimes it is found within creativity. Sometimes it presents as destruction. Nothing falls out of this great world. We all belong. We all are a part. We all present and withdraw. And each of these things speaks of joys and of sorrows. Nothing is left out.

We push ever further along, ever deeper. We pay attention and it all becomes a dance. Dance. Another useful metaphor. Sometimes I hear that phrase about our lives being a dance, and I think of that lovely song “Lord of the Dance.” When I first heard it I thought it might be one of those ancient stories about Jesus, caught in one the early documents of the Christian church, the “Acts of John,” preserved within a medieval song. Turns out it was composed in 1967.

Of course this pointing should be both ancient and modern. The truth of our ancestors, and for us, closer than the blood coursing through out bodies.

Dancing is a theme of the spirit. And it is the second thing I present to illuminate “bread and roses,” to illuminate “The essential world is intrinsically pure and clear. How are mountains, rivers and the great earth at once produced from it?” To illuminate that question mark. Each of these things point to the way of the wise heart.

“Bread and roses.” “The essential world is intrinsically pure and clear. How are mountains, rivers and the great earth at once produced from it?” It is a dance.

It is the dance of our lives. Not some other life, but your life, precious and unique, just as it is, and just as it can become. And mine, too.

Now this. Now that. Birth and death. Love and hate. Work and rest.

Sometimes we lead. Sometimes we follow.

But always, it is a dance.

And an invitation to dance.

The dance of the wise heart.

So…

Dear friends…

Let it be a dance.