Journeys on the Silk Road Joyce Morgan & Conrad Walters 2011, 2012, Lyons Press, Guilford

Thus shall you think of this fleeting world:

A star at dawn, a bubble on a stream,

A flash of lightning in a summer cloud,

A flickering lamp, a phantom, and a dream.

Diamond Sutra Dharani

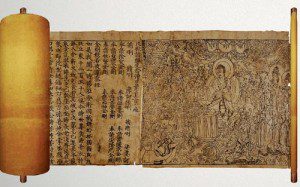

I read Journeys on the Silk Road (provided to me by the publisher) while flying from Providence to Portland, Oregon, on my way to the bi-annual conference of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association, an association of Soto Zen Buddhist priests in North America. Somehow that seemed appropriate, as the subject of the book was the discovery of the Dunhuang Diamond Sutra, the oldest known printed book, published as announced in a colophon to the book, in 868, together with a treasure trove of other documents, mostly, but by no means exclusively Buddhist.

The subtitle for the book is “A desert explorer, Buddha’s secret library, and the unearthing of the world’s oldest printed book.” Pretty much says it all. The book is a well-written and fast paced account of Marc Aurel Stein, born a Hungarian Jew and died a respected scholar and knight of the British Empire, and at the same time reviled to this day in China as a looter and brigand, who in the first decade of the Twentieth Century brought to light some astonishingly important ancient texts, foremost among them that Diamond Stura.

The authors acknowledge the issues surrounding Imperial Europe’s quest over the past few centuries to scoop up the world’s artistic and cultural treasures, and lay out the issues succinctly in the concluding sections. The book recounts how in 1931 the British Museum, which houses much of what Dr Stein carried away, received a letter of protest from the Chinese National Commission for the Preservation of Antiquities, reading in part:

“Sir Aurel Stein, taking advantage of the ignorance and cupidity of the priest in charge, persuaded the latter to sell to him at a pittance what he considered the pick of the collection which, needless to say, did not in any way belong to the seller. It would be the same if some Chinese traveller pretending to be merely a student of religious history goes to Canterbury and busy up the valuable relics from the cathedral care-taker.”

And it wasn’t only the Chinese who saw this acquisition as the rough hand of imperialism. The renowned scholar and translator Arthur Waley made much the same argument. “(I)magine how we should feel if a Chinese archaeologist were to come to England, discover a cache of medieval MSS at a ruined monastery, bribe the custodian to part with them, and carry them off to Peking.”

While acknowledging these issues, their purpose in the book is mainly to present the high drama and adventure involved in Dr Stein’s competitive chase with other scholars from other European powers to obtain these artifacts.

And whether Dr Stein is a villain or hero, or, more like most all of us, some admixture, there’s more than a little high drama, and low, as well as lots of adventure to make up this book.

Using primary sources, and it looks like they read pretty much everything available, including a large cache of letters from and to principals, they’re able to paint a lively picture of events. Admittedly for me occasionally their attributions of emotions came across a tad too novelistic for a “true” life account. However, this isn’t a scholarly tomb, as deeply researched as it obviously is, but a popular accounting of the finding of Dunhuang Diamond Sutra.

Among the concluding chapters is an attempt to describe Buddhism in the West, which perhaps because I know too much about it, I found the least useful, impressionistic to a fault. And to my mind, better off not written.

The book itself, and on a whole, I delighted in. Particularly how it sketched the lives of the principal players, both European and Asian, and of Dash the great, the terrier that accompanied Dr Stein on his adventures, and they are adventures.

And while mostly concerned with the adventure of it all, helping for me to make it a good read, there are many facts addressed. I’ve already mentioned the issues around cultural theft. Sprinkled throughout are tidbits of historical interest.

For instance, among the interesting facts I learned was that while the Diamond Sutra is the oldest clearly dated printed book, there are in fact two other publications that are likely a hundred years older. Both are, interestingly, Buddhist documents. Among these are various charms created at the behest of a Japanese empress, with printed lines from Buddhist texts on small pieces of paper then put into small wooden containers, in a manner similar to a mezuzah, although I don’t think they were ever posted at doors. The other from about the same time as the charms is a copy of the Dharani Sutra found in the Bulguksa Jogye monastery in Korea. While there is general scholarly agreement on the dating of these documents, and their preceding the Diamond Sutra, they lack that precise dating the Diamond Sutra has thanks to that precious colophon.

On a whole? Footnote stuff, no doubt.

But, for me, an absolutely riveting read.

And I recommend it to anyone looking for an entertaining read, but one that will leave the reader with numerous challenges about many things.