THE LUCK OF THE IRISH

A Sermon of Human Possibility Preached on a St Patrick’s Day

James Ishmael Ford

17 March 2013

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

Love is never defeated, and I could add, the history of Ireland proves it.

John Paul II

The world, as one of my teachers once said, is made of stories.

Stories tell us where we came from and who we are. And they point to what we might become.

Those who know me at all know that my father, James Ford, Senior, was a ne’er-do-well. We moved around a lot, just ahead, usually, of some sort of trouble. Moving meant taking what fit into a car. So, we really had very little by way of things. But, he was a great one for stories. And while the ground under those stories shifted a bit too fast for a child’s natural conservatism, nonetheless his stories gave me my core sense of family identity. On my mother’s side we were American mongrel. But, as far as my dad was concerned, my mother was the mother of Irish boys.

Throughout my childhood my dad asserted how he was the only child of the family born in America, and that all six, or sometimes seven older sisters had been born on the Old Sod. Years later I decided I’d take advantage of the Irish law of return that says, or, I gather, said if one grandparent was Irish, well, you are, too, and grab myself a passport. Never a bad thing to have a second passport, I thought. However, a little research revealed that while all four of my father’s grandparents were indeed born in Ireland, he had in fact cut out a whole generation of our proximity to Erin. Since then some have told me that anecdote was a pretty solid indicator he was indeed fully Irish.

My next complication around this identity thing and the stories that carry identity arose a while back when Jan & I decided to give each other genetic tests for Christmas. Turns out there are two kinds. One will tell you where your ancestors come from. The other is scientific. By mistake we purchased the scientific ones, which require a couple of genetics classes in order to interpret the data they provide. After trying to figure out some gross facts, we filed the documents away figuring that was a grand waste of money. Not too long after, wonderfully, because the testing site we used also enrolls one on lists that allow genetic cousins to become aware of each other, out of the blue I was contacted by a cousin who turns out to share my paternal line genetic markers out to some sixty-odd places. That means we’re very closely related.

But, he’s a retired Australian sailor of Anglo French decent. I figured it’s the Viking thing. The Celts of far Western Europe and the British Isles before the arrival of the Vikings, you may not know, didn’t appear to be fair and have red hair, but rather were, at least according to the Viking’s descriptions, smallish people with dark hair, dark skin, and dark eyes. So, I assumed a summer vacation raiding party deposited this Australian’s and my common genes on Ireland’s Eastern shores before or after doing something similar in England.

But, no, said my cousin, retired and apparently with a little too much time on his hands. He actually traced our common ancestor to one of several longships sailing into Rouen, in 911. A bit more than a century after that our ancestor now sporting a fancy French name, de la Poer, accompanied William, the Conqueror, on his expedition to England. And a hundred years after that, more or less, four of five brothers, sons of the Sherriff of Devon, Bartholomew de Poer, accompanied Henry II to Ireland, where their army put down an uprising. For their efforts the brothers were rewarded with County Waterford.

However the fortunes of the de Poer family, eventually apparently more appropriately named Power aren’t my stories. Rather, something in the neighborhood of seven hundred years later, a peasant from the next county over named Ford immigrated to America. What we know today is that whatever he thought his family connections were, and of course, in many ways the real family was that Ford family, also, he was a direct genetic descendant of one of those Power brothers.

I’ve brooded over that fact. Rape? Not unlikely. A kitchen maid seduced? Certainly possible. One friend even opined an illicit love affair, but real love. Sure. And, whatever, everyone comes from someplace else somewhere along the line until we get to our truest home in Africa, somewhere near the Great Rift Valley it seems, where the real human Eve and Adam differentiated out from other great apes. But, seven hundred years in Ireland for that paternal lineage, and no doubt much much longer on my maternal side probably still gives me adequate claim to Irishness.

Well, sort of. This kind of claiming is in a way an American thing. Not long ago I was talking with an Irish friend, by which I mean someone born and raised in Ireland who snorted when I said I was Irish, too. Rolling his eyes he noted how many Americans of his acquaintance so casually say they’re Irish. He smirked. I swear he smirked and said, “You’re all Americans.” I think he meant it kindly. Although that smirk did lead me with some questions.

No doubt I am, and we, what’s left of our line are fully American. And there’s something peculiarly American about how we hold our ancestral connections. We Irish Americans like, for instance, so say how much we’ve done for the country.

So, just to tick off a little of that, eleven people of Irish descent signed the Declaration of Independence, fully half the Union army’s rank and file were Irish. Sadly during the exodus from the Great Hunger, my people would disembark from the famine ships and Union army recruiters were waiting with a small bonus for those willing to be canon fodder. In more recent history we can count our contributions shaping this nation including from my personal favorite, Mother Jones, as well as President John F Kennedy, the immortal Tip O’Neill, the wondrous Eugene O’Neal, and can I say, I have to, our current president, Barack O’Bama. We nearly all feel we all have a little of the Irish in us, and many of us in fact do.

Now despite having been here from before the beginning, the story of the Irish in America is also very much an immigrant’s story, with beauty and sadness. Prejudice against the Irish raged in the middle of the nineteenth century, and continued in various ways right to the middle of the twentieth century. We’re all aware of that sign declaring, “no Irish need apply.”

The path into the heart of this country was often ugly. In my life I think of the demonstrations in Southie during Boston’s busing crisis. And how Irish Americans paid for most all the bombs that exploded and bullets, which were fired in Northern Ireland’s Troubles. And before that there were those terrible days during the Civil War when Irish mobs rioted and lynched blacks in New York City. That hard time on the road, as one jaundiced observer tagged it, as the Irish gradually became white.

And the Irish became white. Now there’s a story. I’ve particularly thought about that, how the Irish were not always considered white, and with that, of course, with that as naturally as the dawn follows the night the question: what does whiteness means? Particularly as it matters so much, or has, I desperately hope it is dying as a marker for whether one is on the inside or the outside of the American story of one’s children doing better than oneself.

These are, you may have noticed, particularly hard times, the first, perhaps in American history where the young of today, writ large, might not do as well as their parents did. We stand in dangerous times. Nothing lasts forever, not people, not countries. But, also these are times pregnant with possibilities. And among those possibilities, one is that perhaps, just possibly, we can put a stake in the heart of American racism. It can go several ways, of course. Hard times also incline one to turn in, and to protect one’s own. We can get more tribal, and I mean that in the worst possible sense.

But, we don’t have to turn inward like that. We can open our hearts ever wider. Hard times can remind us that that list of who is us, who is ours, can expand just as easily as it can contract. It has been part of the American genius to include, to gather together. Once my people were caricatured as looking more like monkeys than humans. Now one author has described our struggle into the mainstream as selling out those others who were also at the bottom of America’s economic system. Those riots and lynchings in New York were among the poorest of the poor struggling to survive in a tribal way. Another hard truth is that part of our Irish ability to assimilate into something bigger was the fact we really didn’t look all that different from the mainstream of the country at the time.

But, here’s a really interesting fact. Whatever our race we don’t look all that different from the mainstream of our time. Race really is a construct with almost no genetic significance. And while I am proud as can be of my Irish ancestry, and the rest, bottom line, we’re all related, coming as we really all have, from somewhere out at the true homeland, the true Eden, our true dream home somewhere in the vicinity of the Rift Valley. There’s a story.

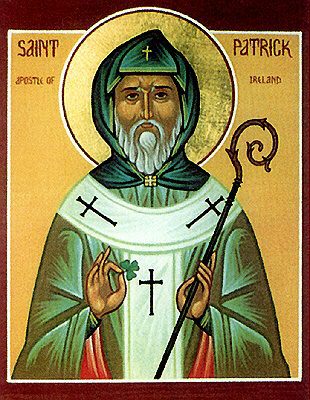

So, what’s my take away for today, the Feast of St Patrick, the nation’s annual recollection of our Irishness? Well, among other things we of Irish descent should better than most see through the lies of race. Our story is one of overcoming, of becoming larger.

Here’s a bit of that story. We come to this country from many things, actions and situations. Violence, perhaps. Love, you bet. The great Hunger and the choice of leave or die haunts my people. Others came involuntarily. Many, maybe most came dreaming dreams of something better for themselves and their children. That’s true even for those who were here when the Europeans arrived – they, too, come from the Rift Valley. We came poor. More rarely we came rich. We came every color available to our human condition. We bring the cultures, or fragments of cultures that nurtured our ancestors. We bring words and figures of speech. All coming here, to a land of many stories, and one.

We find we need not turn on our immediate or near family to discover the family is in fact much larger. We may have a home in Ireland. Maybe all of us do, in one sense. But we also have a home on the Rift Valley. And that’s even truer. What we know is if one or some of us have done well, then the family obligation is to reach out a hand, and bring another along. ‘Tis the Irish way.

Loving our family, that hand should be held out to as many as possible.

To the whole family.

To all of us.

‘Tis the human way.

Don’t you think?

Amen.