A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION TO LIBERAL RELIGION

Unitarian Universalism in a Thousand Words

James Ishmael Ford

Back in the mid nineteen seventies, after I left the Zen monastery that had been my home for several years, I stumbled upon an early nineteenth century pamphlet titled “Unitarian Christianity.” After reading it I immediately looked for where the local Unitarian church was, now called, I saw Unitarian Universalism. I fell asleep during the service. But, later, at the coffee hour I met with people who intrigued me, fascinated me, and eventually opened a new spiritual way for me.

Over the years that have followed I’ve reflected on this tradition, a lot, where it comes from, what it is, and where it is heading.

Personally, at the beginning, I blame the Enlightenment.

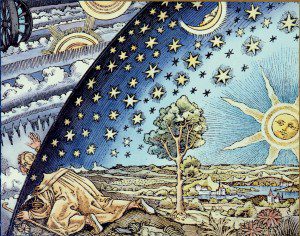

In the eighteenth century when Europeans and North Americans noticed they could take the same skills that were revealing the secrets of the natural world to the workings of the mind and heart and even to their religions, something wondrous birthed into the world. It would variously be called rational religion and liberal religion.

Throughout the eighteenth century some broad principles were worked out through a critical engagement with traditional Christian doctrines and texts. One scholar tagged these as freedom, tolerance, and reason. While these currents would find homes in nearly all religions, by the first decades of the nineteenth century in North America two denominations emerged that were particularly devoted to this approach, the Universalist Church of America and the American Unitarian Association. Despite their deep similarities, for various reasons it would take more than a hundred years for these two communities to consolidate. Finally in 1961, they did, forming the Unitarian Universalist Association.

Each brought a distinct style to the party. In the middle of the nineteenth century a Universalist minister Thomas Starr King called to the Unitarian pulpit in San Francisco was asked how he saw the two denominations. Arguably the first Unitarian Universalist, he replied dryly the Universalists believed God too good to damn humanity, while the Unitarians felt they were too good to be damned. In this little joke we can see these two styles. The Universalists focused on the matters of heart with the slogan “love over creed,” while the Unitarians focused on ethics and the good life with the slogan “salvation by character.”

By the Twentieth century these styles emerged as a naturalistic religion, concerned with life in this world. For a while it would be closely identified with humanism, but unlike organized humanism Unitarian Universalism felt no need to disassociate itself from the family of religions. However this religion was a radical departure from the Abrahamic faiths. Through its own evolution a religion emerged that more closely resembles the traditions of ancient China, Confucianism and particularly Taoism than any of the other Western traditions.

Those who have gathered together under the Unitarian Universalist flag are notoriously resistant to labeling, hostile to anything that might look like a creed. Nonetheless, in 1985, with a second round of voting at our annual convention, the General Assembly of the UUA established a statement of principals and purposes, which were incorporated into the bylaws of the Association.

While the target of disdain from many within, particularly that so much of it is vague and “mom and apple pie,” there are three of the principals which I think speak to the shape of contemporary Unitarian Universalism. Two are theological assertions. And the other speaks to a style.

The first of the theological assertions is that every individual has value. This intuition is grounded in the seventh assertion in the principals that everything is bound up together in a vast web of intimacy. Taken together numerous ethical and social and spiritual concerns arise. How do we live if we feel each of us has significance, value, and that we are all of us related? And, more, what if we see that we are completely a part of this world? Over the years people have taken up one or another of the consequences that follow these intuitions.

The other point is enshrined, at least until there’s another vote, as the fourth principle, which is a call to a “free and responsible” search for meaning. Here we opened ourselves to the full range of spiritual disciplines from prayer to meditation to critical analysis, but always with the call to test whatever we find in conversation within a spiritual community predicated upon a covenant of presence to our own minds and hearts and to each other.

While the radical freedom of this tradition means people can join and do pretty much nothing, to genuinely honor the tradition means taking our lives seriously, to engage that free and responsible quest, to understand deeply what the preciousness of the individual might mean within the context of radical intimacy. I’ve noticed people tend to do this in two ways.

The first is to take these intuitions and style and live them within a larger faith stance. This is sometimes called the great hyphen. Among others there are UU Christians, UU Jews, UU pagans and UU Buddhists. I’m a UU Buddhist. I’m deeply convinced of the principal insights of Gautama Siddhartha, Buddhism’s founder and more the Chan masters of China and their followers in Japan’s Zen schools. And, I engage this tradition as a religious liberal, bringing my confidence in the abilities of ordinary people within all cultures to find everything necessary in this life, to the great matters of life and death. I’ve seen UU Christians do the same thing, with similar success in the transformation of heart.

But, also, I’ve seen people grow wise in this tradition without any hyphens. Simply looking at their own hearts and minds, paying attention to how we each arise in this world precious, and how we are all wound up together vastly more intimately than we can ever describe, leads as naturally as the day follows the night, to a life of wisdom and joy. Some in this approach might think of themselves as humanists. Many would just say they’re Unitarian Universalists.

I love spending time with people in their seventies and eighties and older, who’ve devoted a lifetime to this tradition with critical and radically open hearts and minds.

That’s all it takes.

And that gives me hope.