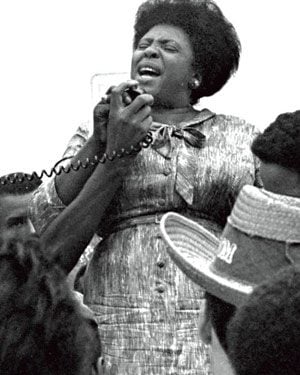

THE PASSION OF FANNIE LOU HAMER

6 October 2013

James Ishmael Ford

Senior Minister

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

Not out of mere charity, but because peace in our time requires the constant advance of those principles that our common creed describes; tolerance and opportunity, human dignity and justice. We the people declare today that the most evident of truth that all of us are created equal—is the star that guides us still; just as it guided our forebears through Seneca Falls and Selma and Stonewall; just as it guided all those men and women, sung and unsung, who left footprints along this great mall, to hear a preacher say that we cannot walk alone; to hear a King proclaim that our individual freedom is inextricably bound to the freedom of every soul on Earth.

Barack Obama, Second Inaugural Address

Fannie Lou Hamer would have been ninety-seven today.

She was born Fannie Lou Townsend in Montgomery County, Mississippi, on the 6th of October 1917. Her parents Ella and Jim were poor sharecroppers. She was the youngest of their twenty children. Fannie Lou began working when she was six, at twelve dropped out of school, and by the time she was thirteen was picking some two to three hundred pounds of cotton a day.

When she was sixteen she appears to have had a brush with polio, and was no longer able to do hard field labor. But because she could read and write and was obviously smarter than most, she was employed by the plantation’s owner as a time and record keeper, as well as doing the cooking and cleaning for his house.

In 1944 Fannie Lou married Perry Hamer, a tractor driver on the plantation. She would say of her husband, “he was a good man of few words,” and, also, and it would prove important, that he was “steady as a rock.” When she had surgery to remove a tumor, as part of a now notorious program to reduce the number of poor blacks in Mississippi, without her knowledge Fannie Lou was sterilized. Never one to allow adversity to beat her down she and Perry, Pap, as he was known, adopted four children, all from people in even worse straights than theirs. An early hint of what kind of people they were.

The 23rd of August 1962 was a life changer for Fannie Lou. She attended a worship service in Ruleville, where the Reverend James Bevel, an organizer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, urged the congregation to register to vote. Fannie Lou was the first to sign on. She would later explain, “I guess if I had any sense, I’d have been a little scared.” Then continued, “But, what was the point of being scared? The only thing they could do was kill me, and it kinda seemed like they’d been trying to do that a little bit at a time since I could remember.”

She joined a little band of seventeen from out of that service, who traveled on a rented bus to Indianola to register. On that ride Fannie Lou sang to the riders on the bus, and she asked them to join her. The songs she chose, played out of her deep Baptist faith, like “Go Tell it on the Mountain” and “This Little Light of Mine.” These and other songs she chose, after this bus ride would become staples of the Civil Rights movement underscoring the spiritual foundations of the movement itself. Before her it was implicit, with her, it was a shining forth of a deep truth. This was a spiritual struggle, as it continues to be.

As was true throughout the South in Indianola they had a literacy test set up, one that apparently most any white person could pass, but for some reason few blacks could. When pretty much as a matter of course she was told she had failed the test, Fannie Lou replied she would come back every thirty days, which was the required time between tests, until she passed. They got the message and Fannie Lou was registered to vote after her third try.

As she would say many times, “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.” She was not going to lie down and take it anymore.

For registering to vote she was fired from the plantation she and her husband had worked at for some twenty years, and with that their family was driven off the land and from their home. The Ku Klux Klan followed them when they left and fired shots into the home where they had taken shelter. But what followed probably wasn’t what the KKK thought would be the case. As she told a reporter many years later, “When they kicked me off the plantation, they set me free. It’s the best thing that could happen. Now I could work for my people.”

In fact SNCC’s Mississippi organizer, Bob Moses had already heard of her being such a rock on the way to registration, and during the struggle to register, and told his assistant, to go and “find (that) lady who sings the hymns.” He had work for Fannie Lou. Recruited into the Civil Rights struggle she began to travel, to sing, and to call people to their better angels, to a better life for all of us.

She suffered threats, arrests, beatings, and was even shot at. After training in Winona, Fannie Lou and two other activists were arrested and taken to a police station. That night a State Highway Patrol officer ordered another prisoner to beat her with a blackjack he provided. When the prisoner collapsed from exhaustion from beating her, the officer dragged in another prisoner, to continue. It took three days for SNCC to get her released and to a hospital. Fannie Lou never fully recovered from the nightmare, suffered severe kidney damage, and limped for the rest of her life.

But she didn’t stop. Fannie Lou went on to become a major figure in the “Freedom Ballot Campaign,” and most particularly known for her work during the 1964 “Freedom Summer,” where many young white women and men who had come south for the work, found her a surrogate mother during trying and frightening and sometimes dangerous times, offering comfort and song as well as a motherly ear.

That summer she joined an upstart group, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to challenge the state’s all white, segregationist delegation to the Democratic National Convention. Fannie Lou was elected their vice-chair.

Despite enormous opposition they managed to get a hearing before the convention’s credentials committee. Her words were recorded and reported widely. She described her many difficulties, her being jailed, her being beaten. And she concluded, “All of this is on account we want to register, to become first-class citizens, and if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings – in America?”

President Johnson was, and justifiably, afraid the Democratic south would turn, as we know it did turn, Republican because of the part Democrats were playing in the advance of racial justice. He was afraid, “that illiterate woman” as we get from Oval office recordings, could even cost him the election. Trying to handle the situation, the leadership offered a compromise where the upstart Freedom Democrats would be given two non-voting seats at the convention. This was political hardball, obviously, in the face of real danger to the campaign, and reluctantly even Martin Luther King, Jr and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, swallowed hard and accepted it as the price for electoral victory.

But Fannie Lou did not. When Hubert Humphrey told her of the compromise, she responded, and again it was recorded, “Do you mean to tell me that your position is more important than four hundred thousand black people’s lives? Senator Humphrey, I know lots of people in Mississippi who have lost their jobs trying to register to vote. I had to leave the plantation where I worked in Sunflower County… Now if you lose this job of Vice-President because you do what is right, because you help (us), everything will be all right. God will take care of you. But if you take (the nomination) this way, why, you will never be able to do any good for civil rights, for poor people, for peace, or any of those things you talk about. Senator Humphrey, I’m going to pray to Jesus for you.”

The Freedom Democrats lost that battle. But it showed Fannie Lou as a moral force to be reckoned with. The next time around, in 1968, she was a part of an integrated Mississippi delegation to the Democratic National Convention. In the following years Fannie Lou would be active in many more projects and campaigns, including a Freedom Farm cooperative, establishing Head Start, Dr King’s Poor People’s Campaign, and later, the National Women’s Political Caucus.

In 1976 she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She also suffered from hypertension, and on March 14th, 1977, at the age of fifty-nine Fanny Lou suffered a heart attack, which killed her. The crowds were too large for her church, so the service was held at the local High School, where Ambassador Andrew Young delivered Fannie Lou’s eulogy. As he reminded those present and all who have followed, “None of us would be where we are today had she not been there then.” No doubt that’s true.

Personally, I find the great causes require people working from both inside and out. There is no doubt to my heart that without Lyndon Johnson and Hubert Humphrey and a host of other legislators and movers and shakers, who worked, the great advances for civil rights of that time would not have happened. They delivered the legislation.

And, at the same time, without Fannie Lou and a host of others standing on the outside knocking on the door, and knocking, and saying not another day – well, without them, without that urgency, I fear Lyndon and Hubert and all those others would not have pushed as hard as they did, and all of their efforts would have come to much less effect.

Instead.

On that cold November evening in 2004, when Barack Obama was elected president of our United States, many of us watched him speak to us from Millennial Park in Chicago. In that speech he echoed both the great Unitarian Divine Theodore Parker and our American hero Martin Luther King, Jr, and put his own unique twist on their words.

The president-elect said, “It’s the answer that led those who’ve been told for so long by so many to be cynical and fearful and doubtful about what we can achieve to put their hands on the arc of history and bend it once more toward the hope of a better day.”

The arc of history is no doubt long. The arc of history may indeed bend toward justice. But, it bends, I am sure, from the bottom of my heart, because people, human beings, Theodore, Martin, Lyndon, and Fannie Lou, to name some who deserve their names called out, sometimes at great cost, sometimes at the cost of their lives, putting their hands on that great arc, and bending it. Bending it…

This was Fannie Lou’s work. And she reminded us all how it is sacred work.

And, dear ones, it is the work to which we are called, by our faith, by our knowing how intimately we all are bound up with each other.

That simple. Fannie Lou showed us.

That hard. Fannie Lou showed us.

That worthwhile. Fannie Lou showed us.

Amen.