TO LIGHT ONE CANDLE

1 December 2013

James Ishmael Ford

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

Blessed is the match consumed in kindling the flame. Blessed is the flame that burns in the heart’s secret places. Blessed is the heart with strength to stop its beating for honor’s sake. Blessed is the match consumed in kindling the flame.

Hannah Senesh

Three days ago it was a once in seventy thousand year event, the first night of Hanukkah and our American Thanksgiving occurring on the same Thursday evening. I just love it. And, I think, even more than usual, we’re invited into reflecting on the great mess. They both, after all, are such complicated holidays in similar ways, in ways, I suggest, also similar to our human hearts.

First, Hanukkah. There are good reasons it was a minor holiday, made what it is today mainly because of its proximity to Christmas. A few years ago David Brooks, the generally conservative New York Times columnist eloquently enumerated the problems with Hanukkah. “It commemorates,” he wrote, “an event in which the good guys did horrible things, the bad guys did good things and in which everybody is flummoxed by insoluble conflicts that remain with us today.” However, somewhere along the line, what was essentially a fundamentalist revolt against multiculturalism became a song of the small in the face of the great, of the weak standing against the strong, of a light shining against all odds, against the dark.

And then there’s our American Thanksgiving, which is similarly, shaped by clouded antecedents. George Washington proclaimed a day of thanksgiving, but only once. Thomas Jefferson never made a thanksgiving proclamation, at all. For a hundred years it simply was not a national event. Not that there weren’t thanksgiving celebrations. Harvest festivals and days of thanksgiving are pretty close to universal, and so of course there were all sorts of local days of thanksgiving in various American communities in our first hundred years as a nation.

But, it was only with Abraham Lincoln that we got our annual national day of thanksgiving. He and his recent predecessors had for years been petitioned to proclaim a thanksgiving holiday by Sarah Josepha Hale, editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, a wildly popular magazine in its day. And it was Hale, incidentally also the author of Mary Had a Little Lamb, who pretty much cooked up out of very little information the idea of the pilgrims and the Indians celebrating together as a universal backstory for a day of thanksgiving. It was an idea and a story that, in the depths of the Civil War, looked pretty good to the president.

Of course, that story which symbolized cooperation had a terrible worm at its heart. As American Indian activists, and particularly the Wampanoags who were the actual Indians on site, have been pointing out for decades, the story Hale told has little to do with reality. And most important that near mythic Pilgrim and Indian thanksgiving was a moment in time just ahead of a terrible genocide. And, so, today, we cannot observe our American thanksgiving without also remembering those who have been hurt, terrorized, and decimated on the way to our holiday.

And yet, knowing these things, we continue to celebrate Hanukkah, we continue to celebrate Thanksgiving. There are reasons for this.

Now, some do so by selective attention, thinking only of the good things about Hanukkah, about Thanksgiving. And I’m not completely opposed to the power of denial. There are times. But, for the most part, and certainly at those push come to shove moments when it really matters Pollyanna eyes betray us. And today as we are invited into a reflection on deeper matters, I suggest, we look straight on and see what we see.

Now, as many here know, I have a continuing interest in ethics, or more specifically Buddhist ethics as informed by the Bodhisattva precepts. The core of which are ten precepts, not unlike the Ten Commandments, although I find them a bit more useful in my regular lived life than the biblical set. They’re seen not as God given, but as observed for their ability to bring us to a harmonious life. So, perhaps it isn’t all that unreasonable in the study of them a favorite ploy is to posit situations where, in order to keep one of the precepts it is impossible to avoid breaking another.

For instance, the Korean Zen master Sueng Sahn liked to present a situation where you’re sitting on a log in a glade in the middle of a forest. Suddenly a fox rushes out of the surrounding woods and dashes under the log on which you’re sitting. Moments later a hunter follows, looks around and demands to know where the fox went. So, let’s see. The major precepts involved in this situation are no killing and no lying, or, as some prefer to present the precepts, preserve life and speak truthfully. Those who suggest avoiding the conflict by maintaining a noble silence are pushed. The master would reply, No, the hunter then points his gun at you. Choose the precept you’re going to break.

The Zen teacher Diane Rizzetto ups the ante. When she sets the conundrum, instead of a fox, it’s a rabbit. And behind the hunter there are hungry children, desperately waiting. What are you going to do?

Life is like that, all mixed up. There are unintended consequences to any action. And the origins of pretty much every thing are complex, mired in this and that.

For instance, let’s return to the Zen teacher Diane Rizzetto. She was a High School drop out and a single mother. Right at the cusp between teenager and adult she was desperate. She saw a classified ad for a legal secretary. Diane understood they paid well and being smart and articulate beyond her formal education she lied her way into the job. Within weeks her boss called her into his office and said it was obvious she didn’t have the skills or experience she claimed she had. But instead of firing her, he asked what it was she hoped to get out of life? If she could do anything, what would it be? She was confounded. Possibly she’d not ever actually been asked that question before. With hesitation, and probably a little fear, she answered her secret desire, to return to school, maybe, eventually to become a teacher. Right there he made some phone calls. Within weeks Diane found herself with a slightly different job, and going to college at night. She ended up earning an MA in American Literature at Brown, and, well, following a trajectory set out of that moment, eventually even became a Zen master.

Now we can look at her life as a straight line, and with that at a critical point a lie, a flat out lie gave her the direction that led to a college education and with that the whole rest of her life. But I think our lives are less linear than that telling suggests. We, to very slightly paraphrase Walt Whitman, are large; we contain multitudes. There are rarely single causes or single consequences. And so that Hanukkah story of candles lit against the dark has as part of it, a reckless and in some ways hateful element. And that story of Thanksgiving has as part of it displacement and genocide. Also, just to continue stirring the pot, today is World AIDS day, a reminder of a devastating disease made vastly worse by simple prejudice. It’s all mixed up.

When we look deeply at how we came to be who we are, if we’re honest, there are going to be lots of mixed emotions. There probably is joy and gratitude. I hope there is. And these feelings can include shame. They can include guilt. Now, truthfully, frankly, we don’t need to feel shame. I feel a bit more ambiguous about the value of guilt; it is the great nudge toward correction of behavior. But as one observer of the complexities of our American Thanksgiving wrote, “we do need to feel something.” Today we’re called into our feeling lives as much as anything else. If our goal is wisdom, we need to open our hearts as widely as we can. That large, that wide heart is the secret.

We only have a couple of minutes left. It’s good to focus. And I want to focus on how we can find our wider heart reflecting specifically on Hanukkah. Here again, a complicated tradition within the Jewish religion, pulled out and made something larger because of its proximity to Christmas, clouded by its foundations as a fundamentalist revolt against what can with some honesty be seen as a multicultural and certainly by the standards of the day, a largely tolerant society.

Now, that ancient struggle at the heart of Hanukkah was not only against oppression of an occupying force, but it was just as much a struggle against pervasive corruption. No doubt the leaders were corrupt to the core, and a response was called for. It really is a both, and situation. Many strands of our lives coming together, making what is. And if we want to be spiritual adults, if we want wisdom, if we want to find the larger heart, we’re going to have to take our communal stories as complicated, involving shameful things as well as noble as critical in advancing us toward a larger view, a healing perspective.

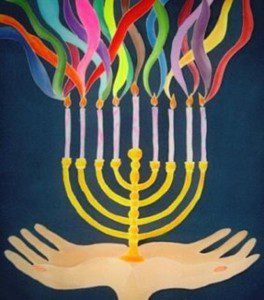

And I think that’s what’s at the heart of the enterprise, our wide, our large heart. In this we can find the mysteries we call love, the mystery we sometimes name God. Here, in particular, I think of the story of the lights, which appears to have been how the rabbis squared the circle of the complicated history of the Maccabees with the dream of something better, of hope, of love. It was expressed in a miracle of light.

And I think our task, yours and mine, is to find the light, that one miraculous light that lasts well past any possible reasonable effort; that shines on the just and unjust, and gives us hope. It points to the path of passion, and of heart. And this is our task, as it has been the task of every soul over the many generations. To take what is given, to look deeply into the matter at hand, and to allow ourselves to be transformed and in that transforming to become spiritual adults. To become people who can take on the work that needs to be done.

There is little doubt today that our liberal religious tradition is the minority position. We are the weak in this struggle for hearts and minds. Right now ours is the unpopular voice that is nearly lost in the thunder of public opinion. And the call for us is a struggle, and it is a struggle not only against every oppression from beyond those walls, but to fiercely resist corruption of this spirit, losing to our own complacency, making it all simply a private affair. That is the small light we are called to notice today, the light burning in our hearts, the light that shows the way of love, and of action.

I suggest this story and our working with it calls us, you and me, to resist the dying of the light, to shine forth beyond all reasonable expectations, to become, each and every one of us by our example, by our willingness to not turn away, by our challenging all authority, particularly that voice in the back of our heads that says turn away.

Each of us needs to be that small candle in the great wind; and in doing so become the miracle.

May this turning of the heart, of our becoming the flame of possibility become the Hanukkah candle. May it burn and burn past all reasonable expectations; transforming us and our hearts showing this beautiful suffering world a way.

Amen.