SPIRITS IN REBELLION

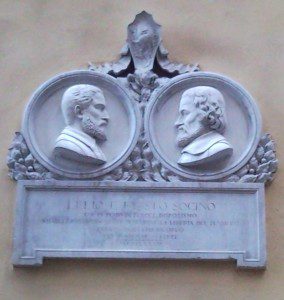

A Brief Meditation on Laelius & Faustus Socinus & the Origins of A Unitarian Reformation

A Sermon by

James Ishmael Ford

26 January 2014

Text

Unnamable God, I feel you with me at every moment.

You are my food, my drink, my sunlight, and the air I breathe.

You are the ground I have built on and the beauty that rejoices my heart.

I give thanks to you at all times for lifting me from my confusion,

for teaching me in the dark and showing me the path of life.

I have come to the center of the universe; I rest in your perfect love.

In your presence there is fullness of joy and blessedness forever and ever.

Psalm 16 (Stephen Mitchell translation)

Today we celebrate our connections to our spiritual cousins in Hungary and most especially in Transylvania. They are a wonderful if beleaguered religious community, so different than us, and yet, somehow profoundly connected. Sometimes people try to shorthand the connections by saying we are descended from those Hungarian speaking Unitarians. Others, like me, get their feathers ruffled when that’s said. They certainly precede our English speaking Unitarianism, but in fact we are two largely distinct, think parallel evolutions of the Christian tradition. And in our case, that evolution has taken us quite far afield from our origins.

But, that doesn’t mean there aren’t connections. And, so, today, I thought it might be fun to do a little historical exploration about how Hungarian speaking Unitarianism and English speaking Unitarianism do touch each other. If you take half the pleasure in hearing this that I had in putting it together, you’re in for a treat. If history or the arcana of theology bores you, well, I sure hope you enjoyed the music.

The Reformation had some significant theological disputes. They played with the niceties of the communion service, and how much faith and works weighed in the question of salvation, but that was most of it. For the most part, the Reformation didn’t touch core doctrines about the nature of God, and Jesus’ relationship to God. One could argue an astonish amount of the energy in the Reformation was in fact about power. Catholics, Reformed, Lutherans and later Anglicans were really focused on who was in charge. Questions about the nature of reality itself, of God and of Jesus were only addressed at the margins of the great struggles for power.

Now there were some anti-trinitarians, those who challenged the status quo opinions about the divine and Jesus’ relationship to that divine, but they were distinctly in the minority, and often were the targets of persecution from both the Roman and major Protestant churches. For the most part today we within our English speaking Unitarianism like to claim all of them as our ancestors. And in a sense it is true. The troublemakers are ours, no doubt. But also, that means we glide over some big distinctions.

As we look at these figures from the beginning of the Reformation we can quickly see anti-trinitarianism does not necessarily mean Unitarianism. Our great Unitarian Universalist saint Michael Servetus, for instance, was no Unitarian, certainly not as most of us would identify the term. As he critically scanned the texts of the Bible Servertus couldn’t find a trinity, and he published that fact. But he never held up the idea that Jesus was not in some very real sense divine.

In fact during the Reformation most who had problems with the trinity had them because of the holy spirit, something amazingly ill defined in the scriptures for a central doctrine of the faith. Often these early anti-trinitarians were, like Servetus, ditheists; that is they believed both the father and the son were divine. But, beyond not believing it was as a trinity, they didn’t agree as to what that relationship of divine father and divine son meant.

Now, a lot who saw scriptural problems with the idea of a trinity, took comfort in those debates in the first few centuries of the institutional church about the relationship between Jesus and God, and noticed the great runner up in the debates, Arianism, where Jesus is not God, but is the first of all created things. So, it avoids rejecting the cherished doctrine of Christ’s pre-existence, that is that Jesus may not be God in substance, but is vastly more than any other person, human or angel.

But, for some, that just didn’t go far enough. And here, I believe, we find the true beginnings of our tradition. Among the many different anti-trinitarians there was a remarkable man and his even more remarkable nephew. These are two people we really should pay more attention to. They will bring us, both our Hungarian speaking cousins and us to be who we are today.

To use his Latinate name, Laelius Socinus, was a son of a powerful Italian banking family that also produced jurists and, significantly, theologians. He was born in Siena in 1304. At first young Laelius studied law, but the family interest in religion quickly pulled him toward theology. He began a systematic study of Greek, Hebrew and Arabic. Years later someone caught up in the inquisition claimed under torture that the young Laelius had denied the divinity of Christ. Others have said that he led a group of Italian thinkers who taught the divide between Jesus and God, and explored what that means. But others, like the great Unitarian Universalist historian Earl Morse Wilbur say none of this is likely.

What we do know is that early on his critical analysis of the texts led him to sail into dangerous waters, and that fairly early on he decided Italy may not be the best place to live. After visiting scholars throughout Europe, he settled in Switzerland. And then as Laelius relentlessly pursued his rational analysis of the scriptures, he really did begin to question the divinity of Jesus. Which, eventually led him to believe Jesus was the natural son of Mary and Joseph. Years later Francis David, Transylvania’s restless intellect and spiritual leader, would be among those who read his reflections.

But, even more important for us was his nephew Faustus, another restless intellect, who happened to inherit his uncle’s library. Faustus was born in Siena on the 5th of December, 1539. Rather than attending university he was educated at home, as I hope you gather, a humanist crowd with an interest in dangerous thought. When the Inquisition came, most would fall under suspicion, and several would die. Like his uncle, Faustus could see the writing on the wall, and embarked on a number of travels, in his case ostensibly on business, but somehow he consistently found himself in the company of the most radical thinkers of the day.

Faustus began to write, and even though he published anonymously, he soon found himself fleeing to Poland, the hotbed of intellectual freedom of the day. There he joined with the Polish Brethren, also called the Minor Church for its relative size. He never formally joined because he didn’t believe Jewish converts needed to be baptized, a view in violation of the tenants of the Minor Church. At the time the Brethren held a largely Arian theology, marking them out as the other proto-Unitarian faith, forming at the same time as the Transylvanians.

While never formally a member he became a significant thinker among the Brethren, first famous for his advocacy of pacifism. But, gradually Faustus’ growing conviction following the same relentless logic as his uncle that Jesus was in fact not God, but the natural child of Joseph and Mary became a distinctive feature of his teachings. But, rather than suffering persecution among the Brethren, increasingly others within the church agreed with him.

This perspective was part of a larger view that has come to be called Socinianism. As the Unitarian theologian and minister Philip Hewett defines it Socinianism taught, “optimism about the capacities of human nature, (giving) emphasis (to) a moral life rather than correct beliefs…” emphasizing free will, and with that a total rejection of hell as some post-mortem punishment for not guessing right about the nature of God.

Today we call this stance Unitarianism. In fact we can accurately say that the Transylvanian church gave us our name Unitarian, and they were the first to use the name Unitarian to describe themselves, but it was Faustus Socinius who gave us our theology.

If it weren’t for the suppression and exile of the Polish Brethren in 1658, there would be three Unitarian churches today. But, because of a printing press at the Polish city of Racow, and particularly the great summation of Socinian thought, the Racovian Catechism, published in many languages, Faustus’ teachings were scattered across Europe. Including in Transylvania.

Now, as I mentioned Transylvanian Unitarianism emerged at the same time as the Polish Brethren as an independent stream of anti-trinitarianism. Hungarian speaking Unitarianism’s principal theologian Francis David, read widely, interestingly, including as I’ve already mentioned, Laelius Socinus, and later, his nephew.

The church David founded, however, was largely Arian, where Jesus continued to have a supernatural aspect. And this is important because it stifles the critical question of where salvation lies. Is it in our hands, or in another’s? Are we saved by Jesus’ sacrifice, or by following his example?

In fact the theological justification for David’s fall from authority as leader of the movement in Transylvania was largely his advancing thinking, which included coming to see Jesus had to be purely human. He preached this while it was still largely unacceptable even among his fellow Transylvanian Unitarians. And when the new king came to power, he had no friends to support him.

Time passed. And for many reasons not the least of which was the product of that printing press at Racow, and particularly that catechism, but also not insignificantly the many exiled Polish Brethren who took refuge with them in Transylvania, within just a few years after David’s death, Transylvanian Unitarians were for all practical purposes indistinguishable from Polish Socinians. So, in many ways, the Unitarians of Transylvania are as much the spiritual descendants of Faustus Socinus as they were of Francis David.

And, it is here that we find the real connection between our Transylvanian cousins and our own English speaking Unitarianism. Following the suppression of the Brethren and their expulsion from Poland, Faustus’ grandson Andrezej Wiszowaty, another largely and unjustly unknown Unitarian luminary moved the printing press to Amsterdam. His writings, such as Rational Religion, and more importantly his publications of his grandfather’s writings including a 1680 edition of the Racovian Catetchism, directly influenced John Locke and Voltaire, and, later Theophilus Lindsey, founder of the English Unitarian Church.

We are all children of Laelius and Faustus Socinus.

Our shared Unitarian faith, honoring Jesus, but putting the focus on our human hearts and minds, and our emphasis on how we live our lives, both as individuals and within community as the central spiritual question, all were first articulated by these two Italian humanist thinkers and spiritual leaders. And faithfully following their spirit, we have continued to evolve and change, each tradition in its own way. As is only appropriate, given that focus on freedom, which we celebrate as our heart.

And, so, as we celebrate our connections to our Transylvanian cousins, may we at the same time, give thanks for these good and holy teachers, who showed us a way to hope and possibility, for ourselves, and for this world.

It is a lovely thing.

Amen.