Yangshan’s Sermon from the Third Seat

A Dharma talk

James Myoun Ford

24 February 2014

Henry Thoreau Zen Sangha

Boundless Way Zen

Newton, Massachusetts

Yangshan Huiji had a dream. In it he traveled to Maitreya’s hall, where he was led to the third seat. No sooner had he sat than a senior monk struck the bell and announced, “Today the one sitting in the third seat will preach.”

Yangshan immediately stood up, and also gave the bell a strike. He then said, “The truth of the great way is beyond the four propositions and transcends the hundred negations. Listen. Listen.”

Case 25, Wumenquan, the Gateless Gate

Yangshan Huiji lived in the ninth century of our common era, and together with his teacher Guishan Lingyou, himself a successor to the great Baizhang Huaihai, was founder of the Guiyang school, the first of the Five Houses of Tang dynasty Zen. There’s a story that when he told his parents that he wanted to enter the monastic life they refused to give him permission. He cut off two fingers to show his resolve. They relented, presumably to head off any other radical demonstrations of his commitment.

As a young monk he traveled widely meeting many of the great masters of his day and had at least one opening experience before meeting his heart teacher, Guishan. Under whose tutelage his insight matured and from whom he received Dharma transmission. The story of their first meeting is preserved. After the young monk made his bows Guishan asked him “Do you have a host, or not?” One of those slippery Zen questions. Yangshan replied that he did, and so Guishan asked him, “Who is it?” Yangshan walked from west to east, and then stood still. A good response, and with that presentation of his insight Guishan had Yangshan enrolled as one of his disciples.

One of the things I like about these teachers, both of them, is that despite the early story of lopping off fingers, the hallmark of the way both Guishan and his heir Yangshan approached the matter was usually gentle, marked by exposition, if not always crystal clear from outside the experience of awakening, but really, always direct pointing. The story of their meeting might seem esoteric, but actually it was a simple and clear invitation from that stance of each of us manifesting fully, and each of us wildly open.

The story of Yangshan’s deep awakening is a good example. He had asked his master “Where is the Buddha’s true abode?” Guishan replied with a brief exposition. In Andy Ferguson’s translation, he said, “Think of the unfathomable mystery and return your thoughts to the inexhaustible numinous light. When thoughts are exhausted you’ve arrived at the source, where true nature is revealed as eternally abiding. In this place there is no difference between affairs and principle, and true Buddha is manifesting.” The account of this story concludes that Yangshan heard these words and had his great insight.

An insight piled upon other insights, of course, and following years of hard practice in the mediation hall. Usually there’s been lots of gradual practice before those sudden awakening stories we hear. But, like a thief in the night, slow or fast, when it comes, it comes. In my experience when the moment is right, it is like a ripe fruit hanging from a tree. All it takes is a small breeze for it to loosen and fall. And so ripe, Yangshan heard a homily, a small pointing to a how and a where, and it was enough.

Enough, that is, to really begin his training, which included much more sitting, study, and a continuing relationship with his teacher and fellow monks.

Still, I think about that homily and its three sentences. First is an invitation to the brilliance of this moment. He calls it numinous. And it is. Of course it is also a dazzling darkness. Pick your metaphor; it is driving you home. Second when we’ve exhausted every idea and all the metaphors, we find ourselves, finally, at that place, at this place of abiding. And then finally we have a description of what it looks like. We arrive at a place where we can’t actually discern a difference between the many things of our lives, including our own particular lives, and the great boundless, the open, the empty.

Yangshan and his teacher were famous for using metaphors and symbols in their teaching rather than using blows and shouts. But blows and shouts or symbols and metaphors, it is all meant for no other purpose than to show us home.

Guishan described it, Yangshan got it.

Yangshan came to be called Little Shakyamuni, probably for the most part behind his back. In time people began to tell a story to explain the title. A man from India visited him. Yangshan asked when had the man left India? He replied he was a magician and had flown from India that very day. Yangshan smiled and asked, “Why did it take you so long?” Without missing a beat the magician replied that he did a little sight seeing on the way. Feeling the moment right, Yangshan gave his own pointer. “While it is clear you have great occult powers, it is also clear you haven’t yet awakened to the power of the boundless way.” The magician is said to have made his bows, and then returned home where he told people he had traveled to China to “find wisdom and, behold, I found Little Shakyamuni.”

Our teacher Robert Aitken always liked how a teacher who is famous for his gentle rebuke of magic is most famous for a story about a dream with its own occult currents, this story that has been gathered as a koan in the Gateless Gate anthology. Me, too. By the bye, the Rinzai master Zenkei Shibayama says that while Wumen ended the story with those words, “Listen. Listen,” in the source document it continues on a bit.

I think ending it where it does is what in fact allows it to be a koan, a public document of our shared awakening, an assertion about reality, and an invitation into our own intimacy. It also belongs so clearly to the style that Yangshan and his teacher and their school offered, a gentle, but relentless pointing.

But before getting to that listen, listen, there are some other parts swirling about, and attention should be paid.

The didactic part, the “four propositions and the hundred negations” are simple enough. The four propositions are the one, the many, being and nonbeing, while the hundred negations, as Shibayama Roshi explains, “are reached by saying that each of the basic four terms has four particular negations, making a total of sixteen; then by introducing past, present, and future, we have forty-eight. These are doubled, as having already arisen, or being about to arise, which makes ninety-six. By adding a simple negation of the original four, we have” our hundred negations. This mild sophistry is simply meant to exhaust our ideas of essentialism, underscoring, and relentlessly, our original boundlessness.

Sometimes this boundlessness is called our true home.

Maitreya is of course the Buddha yet to come, although we have had intimations of him on his way in stories like the monk Hotei, the so-called laughing Buddha, the fat little guy in so many people’s backyards. And in many ways his realm, his hall, not yet fully manifested, is perhaps best found in a dream, a dream not unlike that state of deep oneness we might find in zazen, or, in the play of life itself, especially when we’ve played our hand full and lost. We always lose in the game of life. Always. But, also, while it might seem a cold-water flat, it is also our home.

And there’s the dream home of zazen or the dream home of loss, the hazy moon of our possible lives, which we are also invited into more fully, ever more fully.

That’s the koan.

Stripped away. Everything stripped away. Not this. And not that not this.

Pursuing relentlessly, perhaps we find our lives in the dream, as the dream.

And, then, from there, what?

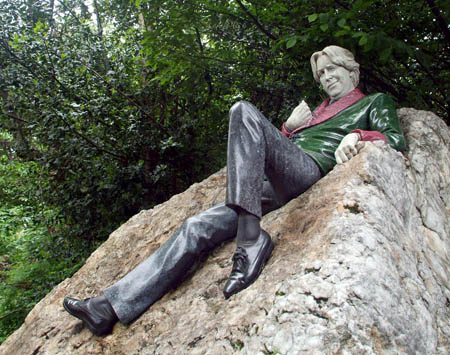

Oscar Wilde points a way for us in his sad opus, De Profundis, a bit purple, but we’re talking the most important thing, so passion and maybe some purple feels very right, to me, at least, and maybe for you. The passion that cuts off a finger to show a commitment to the way, the whole way, the passion that throws us on the pillow, over and over, through the years, the passion that calls us into full engagement even in the ordinary of our lives.

“The important thing,” Oscar wrote after the harrowing of exposure and shame and imprisonment, “the thing that lies before me, the thing that I have to do, or be for the brief remainder of my days one maimed, marred, and incomplete, is to absorb into my nature all that has been done to me, to make it part of me, to accept it without complaint, fear or reluctance.

“The supreme vice is shallowness. Whatever is realized is right… To deny one’s own experience is to put a lie into the lips of one’s own life. It is no less than a denial of the soul. For just as the body absorbs things of all kinds, things common and unclean no less than those that the priest or a vision has cleansed, and converts them into swiftness or strength, into the play of beautiful muscles and the moulding of fair flesh, into the curves and colors of the hair, the lips, the eye; so the soul, in its turn, has its nutritive functions also, and can transform into noble moods of thought, and passions of high import, what in itself is base, cruel, and degrading: nay more, may find in these its most august modes of assertion, and can often reveal itself most perfectly through what was intended to desecrate or destroy.”

Soul. Dream. Really, strange things for a Zen story.

But each of these things are a calling for us, a calling home.

Each thing, triumph and failure, each a pointing, each an invitation.

And that’s what this story is calling to us.

Asking the question.

What part of this isn’t our home?

Cold water flat, a mansion overlooking the ocean, successes, failures, and all those hours on the pillow, each experience lived, becomes our true home.

Which calls us to the nub of the koan, and those words echoed across ages, birthing and dying, rising and falling and rising again.

Listen.

Listen.