IN THE PRESENCE OF GOD, AND ONE OF ANOTHER

A Meditation on Covenant as Spiritual Practice Among Unitarian Universalist Congregations

James Ishmael Ford

12 October 2014

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

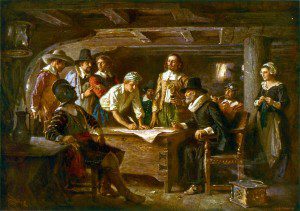

… In the name of God, Amen. We whose names are under-written, the loyal subjects of our dread sovereign Lord, King James, by the grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland King, Defender of the Faith, etc. Having undertaken, for the glory of God, and advancement of the Christian faith, and honor of our King and Country, a voyage to plant the first colony in the northern parts of Virginia, do by these presents solemnly and mutually, in the presence of God, and one of another, covenant and combine our selves together into a civil body politic, for our better ordering and preservation and furtherance of the ends aforesaid; and by virtue hereof to enact, constitute, and frame such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions and offices, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general good of the Colony, unto which we promise all due submission and obedience. In witness whereof we have hereunder subscribed our names at Cape Cod, the eleventh of November [New Style, November 21], in the year of the reign of our sovereign lord, King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth. Anno Dom. 1620.

Mayflower Compact as Recorded by William Bradford

On November 11th, 1620, after more than two months hard sailing, including one death and one birth, the Mayflower and its largely Pilgrim passengers touched land at Cape Cod. This was far afield from the mouth of the Hudson River where the settlers had a Royal patent or charter to establish their colony. They sailed just a little way up the coast and uninterested in continuing the journey any farther, decided to establish themselves at what we now call Plymouth, Massachusetts. While their days were devoted to building houses, at night they returned to the safety of their ship continuing to live in the crowded, dark, and damp cargo hold that had been their home since the beginning of the trip.

In that place they did something very radical. Their original patent had no legal force here. And while they would request another charter, they were also aware of many potential difficulties, as their band was a mix mostly of Pilgrims who had separated from the Church of England, but also of Puritans who had very similar views as the Pilgrims but who had not separated from the established church.

As they drew up their document they used as their model a church covenant, itself patterned on the covenant of Israel with God. Of the one hundred and two passengers, we believe forty-one of them, representing the large majority of the male passengers, including all save one of the free men, three of the hired workers, and two of the nine servants, all signed the document. It was ten days after they had arrived, November 21st. The document has come to be known as the Mayflower Compact. Its consequences have played out in many directions. Most see in the Compact the inspiration of our Declaration of Independence as well as our American Constitution.

While the course of European history had largely been based on the subjection of the weak by the powerful, this radical idea of social contract, the idea that people should gather together in some equal way was beginning to be whispered across the European continent. And now it had happened. With this simple act, a spark was definitely struck. However, what is most important for us here in this Meeting House, today, is how that document, while very much the ancestor of our whole democratic way of life, it was also at its heart a spiritual document that would in good time lead to us.

In the years that followed here in New England the sometimes implicit, sometimes explicit Enlightenment principles of freedom and reason and tolerance would follow that idea of covenant like the day follows the dawn. Those old Calvinists could never have dreamed as they banded together in the dank, dark hold of that ship and created a covenant of mutuality that they would birth such a radical religious idea as would become us, Unitarian Universalists. But they did. And here we are, their most unlikely descendants.

Now it should be noted there are other unitarianisms around the globe that do not depend upon a congregational polity with mutuality, rule of the governed as its guiding institutional principle, to uphold individual freedom – the Unitarians of Great Britain and Ireland both maintain presbyterian polities, rule by elders, and Hungarian speaking Unitarians maintain modified episcopal polities, with that monarchal like rule of bishops, modified, of course. Modified. And, this is important; all these unitarianisms have to one degree or another a sense of the preciousness of the individual as central to their spiritualities.

But that is how it happened here. And how this happened in America and how covenant became so central has had substantial consequences of emphasis and eventually come to be at the heart of our very spirituality in this Meeting House today. Today our liberal faith is the heir to a fairly radical congregationalism, rooted vastly more in covenant than in creed, a statement of faith that one must subscribe to in order to belong.

From very near the beginning of our Unitarian Universalist tradition we rejected creedal assertions in defining ourselves. We have felt the spirit was free and so human beings should also be free. And rather than finding some formula of belief that people needed to adhere to in order to belong to one of our congregations, we instituted covenants.

For us a covenant was, as we can see in the Mayflower document, originally a three-way contract, inspired by the founding myth of Judaism as a covenant between God and with and among a people. For us the covenant became a contract made between people, between you and me, and, and this is important, before that larger out of which we take our being, within which we live, and to which we shall in time return.

Many, although by no means all of us prefer not to use that freighted word God to describe this larger of which we are part. But, truthfully all words, be it God, the cosmos, the world, Gaia, interdependent web; they all fall short of the reality of this intuition of our hearts. But however we name it, or resist naming it, we do acknowledge within our covenant that you and I are standing before, coming out of, standing within, again the language fails, but in this covenant we see ourselves as part of something larger, of our highest, or if you prefer, of our deepest aspirations.

You and I are precious and unique, and passing. And we belong to something larger, a wild and mysterious web of interdependence. And it is before this mystery we make our covenants.

Now these covenants are living documents. And so they do need revision. Within this particular congregation we’ve had three. I find it fascinating and compelling that over the past three hundred years we’ve only rewritten it twice from our founding document. I believe these documents are sufficiently important we should be hesitant before changing them, and we here have been.

And these covenants have worked. We have gathered together and stood together through rough times and good, and as a community we have prospered. And as individuals we have been given the opportunity to grow deep.

And that’s what I want to point out in our remaining time today. Out of this spirituality of covenant a spiritual discipline has emerged.

First, let me unpack that phrase “spiritual discipline,” just a little. First, “spiritual.” For me the meaning of that word is found within its etymology. It comes from the Latin spiritus, meaning “breath.” Similar usages are found around the world. The Hebrew ruach, the Greek pneume, the Sanskrit prana, and the Chinese chi all derive from their language’s word for breath and each stands for that deepest thing in human life, that which gives life, that which gives meaning. The spiritual enterprise is about life and meaning. Spirituality is the task that arises out of our, as the UU theologian Forrest Church said so many years ago, knowing we are alive and knowing we are going to die.

I suggest the spiritual life is all about this knowing we’re alive and that we’re going to die. And our spiritual quest is to find meaning and purpose within our precious life and our certain demise. It is our seeking to know with our full hearts that greater of which we intuit we are a part, and which we are called to find that is the substance of our faith tradition. We are called from the depths of our own being, from the mystery of our connection to each other and to the world, each of us, as individuals, to know these connections and to live our lives from that knowing.

We are being invited into a place where we move from an idea to an experience. The method is paying attention. The practice of covenant is a practice of paying attention. To ourselves. To each other. And to the world. In our willingness to just be present, things happen. Our hearts can be touched in ways we can’t even anticipate. And the wonder is, it comes to us, it comes to us however we name or do not name that mysterious unity. It comes because we are willing to be present to what is.

This encounter may happen in this Meeting House among us in this service. It might come to us when we’re teaching a class in religious education. It might come to us when we’re working at the food pantry or taking a sandwich down to Harrington Hall. It might come to us as we’re walking along the beach on an Autumn day with a friend. It might come to us as we look at a freshly fallen leaf on the ground.

Pure presence. Just this. Just this.

However it happens, when we find that moment we discover the boundaries between our individual lives and the life of the world begins to dissolve. Small insight. Great one. Usually we have many experiences over many years, smaller and larger insights, all coalescing over time into wisdom. What we discover is some great dynamic, like electricity leaping between us as individuals and us as part of something larger. Or. We are each of us the vine, and we are each of us the branches thereof. Not an idea. An experience, a body knowing, something that grows more deeply over the years.

And, I suggest, finding this insight is worth a great deal. It brings a certain peace to us as individuals, knowing even as we are a part, we are also the whole, and this knowing or openness can inform how we encounter each other and the world. It is the source of our ethics, our intuition we need to work for each other, and for this planet.

It’s that important. So, rather than just knowing life teaches us, and wait, some of us take the bull by the horns, and add that second word, “discipline.” We take on the disciplines of spirituality such as found in our way of covenant, in our covenant of presence, to push the river just a little. Actually, some of us wade in the shallows, some of us swim out, some of us throw ourselves into the depths. Each moment a practice of presence.

Taking this on as your practice and how, wading, swimming, or diving is your choice. We have no compulsion on our way. Although, I need to point out the clock ticks. And this work is the great work of being human.

And of course, there is no guarantee in this spiritual work. Those precious moments of insight, they come to us out of the blue, like an accident, sort of like crossing a street and being hit by a bus. But, and this is so wonderful, spiritual disciplines make us accident-prone. As such they’re worth a lot of effort.

And among the many spiritual disciplines of the many religions of the world, we have ours. We find it in being present to ourselves and to each other, open to discovery, open to possibility, open to mystery.

What is something wondrous is as we attend to this work, and it works.

So, my advice. Throw yourselves into the project of presence, into this great covenant we have among us, presence before the mysterious web of reality.

Throw yourself into the depths.

Pay attention.

Notice.

Open your heart to what is and what may be.

This is the substance of that covenant, of our covenant.

To be present.

And in the goodness of time, you will find, deeply, personally, viscerally the way is broad and generous, and its heart is ours.

Our way.

Amen.