INDICTMENT

A Meditation on the Empire and a Promised Land

James Ishmael Ford

30 November 2014

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

When the spirit struck us free

we could scarcely believe it

for very joy.

Were we free

were we wrapt

in a dream of freedom?

Our mouths were filled with laughter

our tongues with pure joy

The oppressors were awestruck;

What marvels the Lord works for them!

Like a torrent in flood

our people steamed out.

Locks, bars, gulags, ghettoes, cages, cuffs,

a nightmare scatttered.

We trod th elong furrow

slaves, sowing in tears.

A lightning bolt loosed us.

We tread the long furrow

half drunk with joy

staggering.

The golden

sheaves in our arms.

126th Psalm

adapted by Daniel Berrigan

Once upon a time, so very long ago we can’t count, and in a land so very far away no one alive today has been able to travel to it by road or ship, there was a great empire. Let’s call that empire Egypt. It’s not the Egypt on the map, a very interesting, if sometimes dangerous country, like pretty much all countries in greater or lesser degree, and can be visited if you have time and can afford it. This Egypt I’m telling about is actually a country that can only be traveled to in dreams. Maybe you’ve been there. I have.

Anyway, within that empire that was Egypt there was a tribe. They had once been an important people; at least that’s what their poets said. But for generations they had been slaves, used, abused, and thrown away at the whim of their owners. And even when not slaves, they continued to be mistreated, given the worst educations, and most of them given only the worst jobs, and many no jobs at all, Although one of their number had once risen to be the Pharaoh’s prime minister, for most theirs was a hard, and dangerous, and often brutal life.

Finally the Pharaoh was worried there were too many of the tribe in the country, and feared their strange ways would poison the empire’s children, and finally after making it as hard as he could for them, it turns out it can always be worse, but when they didn’t leave, he ordered all their newborns be thrown into the Nile, the great river that snaked down the heart of the empire.

As it happened it was just then a woman gave birth to a boy. Let’s call her Jochebed. She feared for her baby’s life and hid him for three months. After which she came up with a plan. Learning where the Pharaoh’s sister liked to bathe, and hiding nearby in the rushes, she put the baby in a small ark, a tiny boat, and pushed him out into the current where he was carried to Pharaoh’s sister. Let’s call her Bithiah.

Jochebed’s desperate scheme worked. As soon as she saw the babe floating toward her, Bithiah fell in love. And so the baby was taken into the royal family and raised as one of theirs. Because this is a story Jochebed was able to get employment as the baby’s nurse. And raised by both his natural and adoptive mothers Moses grew in stature and wisdom and, of course, as a prince of Egypt. During these years Jochebed also whispered his whole story into his heart.

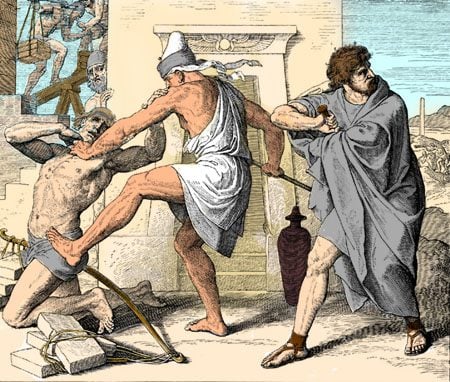

Then as a young adult he witnessed the brutal beating of a slave from his tribe by an Egyptian overseer. Incensed, possibly overtaken by thoughts of his life of privilege and maybe his sense of guilt that he was a prince while he could just as easily have been the beaten slave, he struck out and killed the man. Then fearing for his own life and maybe the possibility of exposure, or some other reason or mix of reasons, we really can paint any picture we want of his character, Moses fled into the wilderness.

From that the story gets ever more complex and mysterious. He has many adventures, he loves and loses, he works hard, he succeeds in life by the labor of his own hand. Throughout all this he is in fact being prepared. Finally God confronts him in the form of a burning bush and tells him what he was being prepared for. In that encounter Moses is charged with leading his people out of captivity and to the Promised Land.

It doesn’t go well for the Egyptians.

I think of that story, and I think of the Black church in America, and how deeply that story moves in their hearts. And I think of something else…

I’d be shocked if anyone in this Meeting House is unaware of the events in Ferguson, Missouri, at least writ large. Haunting our Thanksgiving holiday: The shooting, the demonstrations, the bizarre Grand Jury process, the finding of no finding, the demonstrations and riots. As I speak things are far from done. There is still the possibility of Federal action and the governor has appointed a commission to investigate the whole sad affair.

And, as happens so regularly within our American culture, everything, right down to the facts on the ground, are disputed. There are two principal narratives about all this. Now this is the most important part, I believe: if you’re white, you are, statistically more likely to fall on one side, and if you’re black, you are statistically more likely to fall on the other side. I’m grateful our crowd here tends to be more difficult to categorize, at least as regards this issue.

But. And. The issue. The issue is not really about the terrible events that led to officer Darren Wilson shooting young Michael Brown. By itself, it would have been a local, if tragic story. But this event has not happened in isolation. Since Michael Brown’s death there’s also fourteen-year old Cameron Tillman shot while hanging out in an abandoned house in Terreonne, Louisiana, eighteen-year old VonDerrit Meyers, Jr, shot in St Louis, Laquan McDonald a seventeen-year old on a vandalism spree, shot in Chicago, Roshad McIntosh, who was nineteen when shot under disputed circumstances, Carey Smith-Viramontes an eighteen-year old girl shot apparently brandishing a knife in Long Beach, California, Eighteen-year old Dillon McGee shot in Jackson, Tennessee, the officers on site claiming he tried to run them down with his car, Mentally-ill nineteen-year old Diana Showman, shot while brandishing a power drill in San Jose, California, and, twelve-year old, twelve-year old Tamar Rice, shot in Cleveland while holding a BB gun. These are all juveniles who’ve been shot and killed in altercations with the police since Michael Brown’s killing. What they all have in common besides their youth, is their race.

Now several observers have commented that in this shooting, the prosecution, or lack of it, and the demonstrations and riots are nothing less than a cultural Rorschach test. In describing what they see, and the fixes, people are often revealing themselves more than unraveling the issues at hand. And, this certainly seems to be true.

Still, there are those patterns, those two larger groupings of our responses to matters of race in our culture. On the side within our communities of color, particularly among our African American communities and with their supporters there is a tendency to see oppression everywhere. And, then the majority community, those of us largely of European descent, so many, most, look at these things and see “no” problems, or, “small” problems, or, “their” problems.

Now, I’m not striving for some mythical middle ground here, where “we all” have lessons to learn. While there are always lessons for all of us, there are at the same time rights and wrongs. There is, along with many issues small and large, a deep cancer within our body politic. You want a “we all” in this, well it’s we all need to recognize our ability to miss the point, seeing our favorite trees, but not the forest.

Professor Javon Johnson put his finger on the real issue, the one that threatens to unravel our community. “It’s not about whether or not the shooter is racist. It’s about how poor black boys are treated as problems well before we’re treated as people.” My friend Doctor Liam Keating observed how in 2011 in my home state of California a black man was eleven times more likely to be jailed for possession of marijuana than a white man, and added how it’s all really about “systematic institutionalized racism, in a country where we lock up more people than any nation now or in history. More than Hitler or Stalin, and those numbers are essentially a reflection of incarcerating about one in three young black men.” Liam concludes, “The system is broken.” And, he adds, to you and to me. “Fix it.”

We want an indictment. This is it.

Here I want to return to the story of Moses and a little of why it is so important in the Black church, and why we who largely belong to the majority population need to look a little more closely, listen a little more deeply, when something like the events at Ferguson occur, and how we, like those in the Black church can look at these events through the story of Moses.

Most, I believe, of us in this Meeting House know that people who study such things deeply tell us the story of Moses and the Exodus are not historical events. Best I can tell there is barely a shred of history, or rather the real history takes place in the Babylonian captivity when the enslaved Hebrews wove together stories of hope and possibility very nearly out of whole cloth. But what they did, those poets sitting beside the waters of Babylon, was weave a truest of true stories, a story of hope, and a story of warning.

Hope for all those who have been oppressed. And, a warning for the rest of us.

Now here’s a bit of good news in this. We are in some ways all of the characters in that story. We’re Jochebed, we’re Bithiah, we’re Moses. And, of course, we are Pharaoh. As Terence reminds us “Nothing that is human is alien to me.” For good and for ill. And I would add we’re all of it, even the things we might consider background, we’re Egypt the empire itself, and the Nile with its life giving waters, and, very much, somewhere deep in our hearts we are the Promised Land, the dream home of our hearts where things are put right.

So, where does the rubber hit the road? How might this ancient story of our heart’s longing touch our lives, lives filled with such disparities, where the poor are getting poorer and the rich richer, and where if you’re black your chances are very bad, indeed?

I think for those of us in the majority, we need to realize that while we can be all the parts the big part that we mostly live within is Egypt, is the empire, and what holds our hearts is Pharaoh. When we don’t see there’s a problem, or the problem is someone else’s, we’re Pharaoh. And those of us in the minority, those oppressed, those who’ve been left behind, we, you are the one’s for whom this story was sung. This story is ultimately for those sitting on the shores of that river, lamenting a home, dreaming, and being promised a home.

Now, let’s think for just a heartbeat or two about that killing, not Michael’s, although I’ll come back to that quickly, but Moses striking down the overseer is the part of the story that I find I keep coming back to. What poured into Moses’ heart in that moment? Rage? Hatred? Shame? And, I think of the people of Ferguson and their reaction not to Michael’s killing, that was demonstrations, but to the fact the Grand Jury found no actionable event. Rage. Hatred. Shame. All of this bubbling up out of those words of nothing actionable, as rage and hatred and shame. Violence and leaving innocents hurt and small businesses many owned by members of their own community destroyed, and lives wrecked.

No excuses. Those who perpetrated those crimes are responsible for what they did. And likely many will be punished.

And.

And what about those who witness the injustices the endless injustices perpetrated against Black Americans and who do nothing? Or, who equivocate, maybe there’s something wrong, but saying Michael was no innocent, or, saying there’s no justification for these riots, and then turning away from the nasty business of pervasive institutionalized racism and the cancer it is within our community? Or, here’s another image: the tender that was waiting for a match. What about it?

No excuses.

An indictment.

Now, not long ago when I preached a sermon on climate change, I was challenged by a friend who asked where was the word of hope in what I said? I responded how I thought there was hope, there was a way through, it’s just that there wasn’t a lot of wiggle room. It’s just that it was hard. Very hard.

Kind of like life.

Well, here we are again.

We are all the parts. Nothing human is alien. We can choose, in some very important ways, we can choose. And with that we are responsible.

So, what side do you want to be on? Egypt? The empire?

Or, do you want to throw in your lot with the disposed, the left behind?

The poets have sung true. And the doors are open. The sea has parted. The way is offered.

The system is broken.

Do you want to go to the Promised Land? Hard though that may be?

The system is broken.

Fix it.

Pay attention. Speak up. Recognize the preciousness of each one of us, and how we are all bound up together in a single garment of destiny. Join your hands with others to oppose what needs opposing, to stand up for what is true. Speak out. Act. And with that begin the journey, that forty-year journey to make this land the Promised Land.

Those who have ears, those who have eyes.

Amen.

And amen.