THE WAY OF A PILGRIM

Or, How to Save Ourselves and the World

James Ishmael Ford

15 November 2015

Pacific Unitarian Church

Rancho Palos Verdes, California

Beirut, Baghdad, and Paris. Hundreds dead. Confusion reigns. People are demanding action. And here we are, gathered once again within this sanctuary. I suggest in order to engage our lives in the world, to make our actions, and right now our reactions more useful than harmful, we need to have a moral compass, a sense of who we are, and what the world is. The closer to reality that sense is, the better chance we have of success as we engage.

I believe our project here as a spiritual community, there is a reason we use the word “church” in our name even if most of us would not identify as Christian, is because we are about finding that compass, that perspective, that place to stand from which we can act in this world woven of sadness and joy. There are many ways we can do this. That we choose to gather in a spiritual community is already to have taken one direction. Today I would like to dig into that spiritual a bit deeper.

One of the joys in living in New England for the past near fifteen years before returning home to California, was experiencing the various architectural treasures that house so many of our Unitarian Universalist congregations there. For instance, a year or two ago I attended a clergy meeting for the first time at the First Unitarian Church in New Bedford, Massachusetts. New Bedford was one of those old cities that built its fortune in the days of whaling. Today it is a city like many in that part of the country in decline. Still, the fortunes from those days linger in various ways, not the least in the ornaments of their churches.

As we filed into the sanctuary for our “chapel service” I found my breath taken away as I saw for the first time their astonishing Tiffany mosaic on the wall behind the pulpit. Even partially obscured by some amateur’s attempt at preservation through a thick application of shellac, you can’t miss how amazing it is, and the luminosity of the mosaic shining though, the image, titled, “Life’s Pilgrimage.” At three hundred square feet it is the largest of Tiffany’s many mosaics.

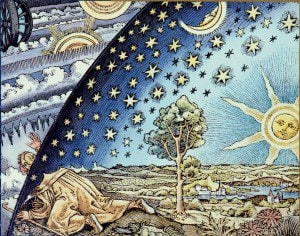

Today, let’s talk about pilgrimage. Seems important, at least to me. And, why, and how we might engage this ancient spiritual practice as contemporary religious liberals facing, well, facing so much. And so, life’s pilgrimage. That mosaic features a bearded man on what is obviously a dangerous mountain path with an angel just behind him. Made me think of that once ubiquitous bumper sticker, “Not all who wander are lost,” a slight paraphrase of a line in a poem in J. R. R. Tolkien’s novel, the Fellowship of the Ring, “Not all those who wander are lost.”

Still, it is easy to be lost. We don’t all have that angel at our shoulder. For me finding that angel is the point. And, with that I’d like to unpack a bit the word “pilgrimage,” and its cousin “quest.” Between these terms I think we find what we can, and what I hope we would be about as a gathered spiritual community. The online version of my personal favorite dictionary for American English, Merriam-Webster gives two definitions for that word “quest.” First as “a journey made in search of something” and second, “a long and difficult effort to find or do something.” “Pilgrimage,” as it turns out, is also given two definitions. The first is “a journey to a holy place” and the second is “a journey to a special or unusual place.”

The dictionary goes on to cite the first usages for both English words in the fourteenth century. That can be a bit confusing as pilgrimage is one of the oldest of spiritual practices, and the idea of a quest is perhaps the oldest literary motif there is. Songs of quest were sung around campfires, and became the subjects of the first bards in far distant antiquity. Let me add in two more definitions. The quest is our human desire to find treasures of one sort or another. Pilgrimage is our journey right into the heart.

Now, like pretty much all spiritual practices, pilgrimage can be a way of avoiding the real deal, becoming tourists rather than pilgrims. There’s that famous story where a businessman, infamous for his harsh dealings with others, told Mark Twain of his plans to take a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. “I’m going to climb Mt Sinai,” he explained. “And from the top of the mountain I’m going to read out the Ten Commandments to the world.” Twain replied, somewhat dryly, I imagine, “Or, you could stay (right here) in Boston, and try to keep them.”

Of course that “right here” could have been Rancho Palos Verdes, but perhaps I digress. I’ve known people who see their spiritual journey as a pilgrimage in a way that misses the real point. The dream quest for them is a running away from the problems and difficulties of life. Pilgrimage is not about running from, but rather going to.

Pilgrimage and quest often come together, like in that Medieval Jewish story of the man who dreams of a treasure buried by a lamppost at the edge of a bridge. Who then takes off on his quest, on his pilgrimage, and after much hardship finds the spot. While digging at the foot of the lamppost a policeman stops him. When the pilgrim tells his story, the policeman laughs and says he had such a dream himself, and in minute detail describes the man’s own basement. But, the policeman continues, you don’t see me chasing off after such things. Leaving the man in peace to return home and dig up the treasure.

Who, as a child or, maybe today, hasn’t had a fantasy about embarking on an adventure and toward some wonderful object? This dream is about as baseline human as it gets, we all, or, just about every one of us, dreams of something better. I suggest the dream is the origin of all quest. And, I think pilgrimage brings the dream of quest down to the earth.

Pilgrimage is about taking that walk, long or short, home, finding where we are, and what we are. And, from that, finding the compass, and having a deeper sense of when and how to act.

One would be hard put to find a religion that doesn’t honor pilgrimage one way or another. There’s the Spanish Way of St James, one of the great Medieval Christian pilgrimage routes, a path a number of friends have walked, maybe one or two here? For Christians, theological or cultural, it is second only, perhaps to making one’s way to Jerusalem. And, that’s just two of many, many Christian pilgrimage sites.

In ancient Judaism the Temple was a destination for pilgrims and even today Jews make their way to that wall which is last standing remnant of Herod’s temple, to remember and to pray. Throughout the Muslim world there are many pilgrimage sites, the great Haj, one of the five foundations of Islam, merely being the most notable. In India, Hindus have numerous sites of pilgrimage. Buddhists make their way to the sites of the Buddha’s life and other great shrines.

Now, pilgrimage is not even bound by the terms “faith” or “spiritual,” at least in its usual sense. Jan & I just spent a week in Washington D.C., it certainly had elements of pilgrimage about it. Or, mixing it all up secular and spiritual, say taking a walk around Walden Pond, near that UU holy site Concord, Mass, something I did nearly annually when we lived in New England. Actually that great round of a walk around the pond, really for a Californian a medium sized lake opens us to circumambulation and its close cousin, walking the labyrinth as variations on pilgrimage.

So, what about us? You know, you and me, faithful and faithless, quintessential religious liberals. Many of us are caught up today more than most with the questions of peace and war, of terror and response. Us. How can we encounter pilgrimage as our spiritual practice, and use it to help us find where to stand, and how to engage? Well, I suggest we can, each of us, claim pilgrimage as part of our spiritual lives. And it’s not that difficult.

Let me offer four points. If you want to try pilgrimage as a spiritual discipline there’s 1) a beginning, there are 2) obligations while on the journey, there is 3) the destination and our relationship with that destination as a goal, and then, finally, 4) there is coming home, where the journey and the goal collapse into the moment of presence. I do seem to return to presence, don’t I? Let me unravel these points, just a little. Let’s see how we can create our own personal pilgrimage, taking us out on the path home.

First, everything begins with attention, the universal solvent of our lives. We notice. We look. We listen. Without attention we’re not on pilgrimage, we are just wandering, wandering among the weeds and grasses. We’re just tourists. With attention, everything becomes sacred. In fact, do this, and you have it all.

Still, there are more things we can do. So, two: those obligations along the way. People on pilgrimage mark the journey out as special one way or another. Often, folk wear special clothing; the medieval pilgrim’s badge leaps to my mind, as do the robes of a pilgrim on Hajj. Sometimes people refrain from eating certain foods for the duration.

Again, I think the important thing here is creating a way of constantly reminding oneself that this is a pilgrimage, not just a stroll in the neighborhood. Although, I believe, done right, that stroll can become the pilgrim’s way. Mark it out in some manner. Carry something, a pebble from the beach, wear that string of beads a child made for you. I wear a small Buddhist chaplet on my wrist.

Three: recalling that destination of our pilgrimage. It isn’t yet home; it is an ideal, a goal, an aspiration. But giving a little heart to the matter, bringing our heart’s longing into the project hints at what home is. Now as a spiritual practice the destination needs to be a real place, it needs to be a real spot in time and space. X marks the spot. Is it a trip to see the site of the Buddha’s birth? Or, to go to Walden Pond and place another stone on the pile next to the site of Thoreau’s long gone shack?

Or, perhaps could it be to some place that you always went as a child, when everything was right? Perhaps it’s a particular stretch of beach? Or, maybe it’s a cabin on a lake? Or, possibly, it’s a walk in the neighborhood? Maybe it’s a trip here on a Sunday? Pick your pilgrimage. And, attending along the way, begin to see what it means to you, what it reveals to your heart. What is your true relationship to this particular spot that is different than your relationship to any other?

And four: that last thing. Coming home. In our coming fully to the place we sought, recalling all the things that led to it, our setting our intention, our bringing our attention, our noticing each step, it’s as easy as falling off a log. Doing this we discover it, the object of our heart’s longing, the true deep, is nowhere other than our own heart, our own body, this very place.

I think of Beirut, Baghdad, and Paris. I think of our ways of presence, and of pilgrimage, and most of all, of coming home. And having come home, standing in that place, in this place, as those tragedies, and we should also remember, as the joys of life come to us, we will know our hearts and with that our actions, our reactions will be filled with grace, and what we do will indeed be more helpful than harmful.

And that’s all that one can hope for in this mysterious world.

But, it is also enough.

So be it. Blessed be. And, amen.