ISHMAEL’S CHILDREN IN AMERICA: A SONG OF ISLAM

James Ishmael Ford

3 January 2016

Pacific Unitarian Church

Rancho Palos Verdes, California

When I was a young Zen monk living in a monastery in Oakland, we were informed that we were getting a VIP visitor. His name was Samuel Lewis, and while he was mostly known as a Sufi master, he had also been acknowledged for his insight by spiritual teachers in a number of traditions, one of which was Zen. Ours was a bit more mainstream Zen Buddhist community and so most of us were expecting for us something on the rather exotic side, sort of a Zen zebra.

We weren’t disappointed. When he arrived I was on the hospitality team, and answered the door. Standing on the front step was an elderly man only a few inches more than five feet tall. He had shoulder length grey hair, a full beard, and oversized black plastic framed glasses. He was wearing the robes of a Korean Zen priest, I later learned put on special for the occasion. Before I could say anything, actually before I could take a full breath he brushed past me and looked around. His first words were, “Wali Ali, take a letter.” A young somewhat pudgy man followed along after him trying to write in a stenographer’s notebook. As the Zen and Sufi master’s entourage of four or five followed he proceeded to examine the large old building that had been converted into a Zen monastery dictating his observations along the way, mostly, although not a hundred percent positive.

After his inspection the murshid, a Sufi title meaning “guide” or “teacher,” finally went to the roshi’s private rooms, and spent an hour or so with her. His students and we Zen monastics went into the kitchen, drank tea and talked about the spiritual scene in the San Francisco Bay Area at the end of the nineteen sixties. We had a lot to discuss. When Murshid Sam, as he was best known, and his students left and we returned to our accustomed silence, I was acutely aware how he had left a physical impression on the space that took days to fully dissipate.

Fast forward a lot of years. I was living in San Diego, working in a bookstore. I’d long left the monastery, and at the time I’d thought I’d left Zen, as well. My marriage had collapsed, I felt pretty lost. And while Murshid Sam had died, almost on a whim I decided I would go back up to the Bay Area to San Francisco and study with one of his principal successors, the formerly pudgy young man called Wali Ali. Spent a couple of years in that Sufi kankhah, their residential center, and while my own spirituality eventually took me in other directions I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for them. The Ishmael in my name was presented to me in those days by one of their sheikhs, or teachers. And I’ve proudly kept it as a token not only of those days, but, of the importance those days continue to occupy in my heart.

Now, to be clear, this was a school of Sufism that no longer saw itself as exclusively Muslim, and many orthodox Muslims wouldn’t consider them part of the faith at all. But in fact a number of the residents and associated practitioners were practicing Muslims. And, it was knowing and watching them that I came to have a sense of a vastly different Islam emerging here in the West than we hear about on the news. And that opens what I would like to reflect on with you today.

We are up to our eyeball’s engaged in the Middle East’s struggles sometimes with justification, and even for good and noble reasons, and sometimes, truthfully, it’s hard to find any good reason why we do what we do there. Frankly, it would be foolish to miss how in our military presence we have fanned and continue to fan the flames of fundamentalism as a form of resistance to the foreigners that pretty much everyone in that region see as invaders, even when wanted we’re seen as a necessary evil. So, I suggest we can profitably do a little soul searching about all that. But, also, Islam is very much on our collective minds. And it should be.

We need to understand it. And in particular we need to understand Islam in this country. I suggest what we’re seeing in the popular media and particularly what we’re hearing from politicians is for the most part not accurate. The biggest problem is reducing Islam to its fundamentalist versions. For instance the religion of Al-Qaeda or the Islamic State is Sunni Wahhabi fundamentalism. Understanding that fundamentalist form of Islam is important, just as we need to see the agenda of fundamentalist movements in Christianity like Dominionist theology. But, and this is so important, like with Dominionist Christianity, as dangerous and frightening as that is, there’s vastly more to either faith than that twisted distillation of fear of the other with a quest for the purity of true belief, which is fundamentalism in whatever flavor you prefer.

In fact the vast majority of Muslims in the world are not fundamentalists, quite likely not much larger a percentage than within world Judaism or Christianity. And specifically, the face of American Islam is in fact, largely, the face of a religion that is about as moderate as Christian Methodists or American Baptists, or, at “worst,” if you will, most like Southern Baptists. They take their faith seriously, but they are also many other things, genuinely part of the fabric of our larger culture. All in all American Muslims are much more about their faith’s many attractive features than any of the scary things we hear associated with Wahhabism or other Islamic fundamentalisms.

I’m not going to spend our time today exploring the basic principles of Islam, such as the five pillars. A simple google search will give you that. Rather, I want to address a more important point too often missed. What I want to hold our focus to here today, is how a rather rich, a startlingly beautiful, and a genuinely interesting Islam is emerging here within the great multicultural experiment that is America.

Now the lists of our sins in this country are numerous. But, despite the fact the majority of us are Christian thanks to the founders who wrote it into our Constitution, we have been able to resist any attempts to create theocratic control in any lasting way. At least so far, so good. And as a result both moderate and liberal forms of Islam have been able to flourish here without significant hindrance. So far. Now as you look at the range of Muslims here, some are indeed fundamentalists. And I have big concerns about Saudi money trying to purchase influence here, particularly underwriting mosques. That noted, most American Muslims are moderates. And the rising influence of organizations like the American Islamic Forum for Democracy and the Center for Islamic Pluralism speak to that moderate voice finding its place here in America. Also, I notice how even those who take Saudi money seem as often as not happy to get the cash, but continue on a much more moderate course than their benefactors might have thought they were buying.

But, truthfully, the ones I really find fascinating are the liberals and progressives. There has been a current of liberal and progressive Islam for, well, pretty much as long as there has been an Islam. But, in authoritarian and theocratic regimes, and these days in states that feel under assault by the West, liberals and progressives of all sorts have suffered considerable persecution. But here in America, a place with an unparalleled freedom of religious expression that liberal impulse is beginning to be explored to the full.

Another major factor in this are our black American Muslims. They’re worth an entire field of study. In the early twentieth century Americans of African decent were first evangelized by the only nominally Muslim Nation of Islam. But the vast majority who found Islam something important quickly moved on to more normative forms. However, here we have both American converts and now several generations who bring are both genuinely Muslim and completely American culturally. And, the degree of their influence on the immigrant Muslim communities that have been following is hard to overstate.

Thanks to these conditions what is emerging is fascinating. This liberal, this progressive Islam is beginning to take shape. Number one among their principals has been holding up the right of the individual to interpret the texts, both the Quran, and the commentarial Hadith. And, actually, with a trend among the most progressive among them, to reject that authority of the Hadith, at all. Like with Judaism, these progressive Muslims believe the ability to discern right and wrong comes with being human and is independent of any particular prophet’s revelations, opening them to full dialogue with any other tradition. Also, right up there with the right of conscience these liberal Muslims fiercely advocate the complete equality of women and men. This is rich stuff. I suggest those who call for a Muslim Reformation, well, this is it, happening now, happening here.

Here everything is on the table, even the institutions are open to challenge. Actually, according to a Pew study Gen X and Millennial Muslims in ever-increasing numbers flatly reject mosque cultures and those questionable influences from those willing to build the buildings and pay the clerics. Instead they look for new and creative ways to live and to engage with each other and their faith. We see something similar happening with the Emerging Christian movement, not institutionally dependent, built around small groups of friends. Open. Questioning. Deeply fertile.

And, here’s another thing worth noticing. Despite the fact that over three quarters of Republicans and too many others agree with the statement that Islam is “incompatible with the American way of life,” American Muslims have in fact been wildly successful integrating into our culture. This is backed by statistics. They tend to be better educated than most, about forty percent as opposed to the shy of thirty percent of the general population having at least an undergraduate degree. And, I think this a terribly important number, according to a Gallup poll taken in 2009, fully seventy percent of American Muslims consider themselves politically liberal, at least by the definitions we use in this country. Of course, knowing those other currents among American Muslims, this should hardly be a surprise.

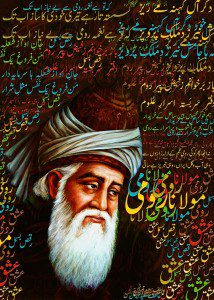

And, of course, then there are the Sufis. Totalitarians don’t like them. Fundamentalists hate them. And here in this country they’re flourishing in all sorts of varieties. For me this is the most interesting of all the forms of Islam. There’s a reason I cherish what has become my middle name. And it is the Sufis. Our own popular culture, and for many of us, our very spirituality, wide and inviting as it is, is being enriched most directly by Sufi poets, and of those most deeply and pervasively Jalaluddin Rumi. As many here know the most popular poet in America today is this thirteenth century liberal Muslim Sufi. There’s a reason he fits into our Unitarian Universalist hymnal.

You want to find the wisdom that emerges in a multi cultural nation where all religions and those with none claim a right to be at the table? You want someone who from such wild openness proclaims our deepest possibility, what is happening here, now, just because of our genuine welcoming? I suggest you need look no farther than that Muslim Jalalluddin Rumi, who some eight hundred years ago sang to us of what he called the one song. Here in Coleman Barks’ translation.

Every war and every conflict between human beings

has happened because of some disagreement about names.

It is such an unnecessary foolishness,

because just beyond the arguing

there is a long table of companionship

set and waiting for us to sit down.

What is praised is one, so the praise is one too,

many jugs being poured into a huge basin.

All religions, all this singing, one song.

The differences are just illusion and vanity.

Sunlight looks a little different on this wall

than it does on that wall

and a lot different on this other one,

but it is still one light.

We have borrowed these clothes,

these time-and-space personalities,

from a light, and when we praise,

we are pouring them back in.

Okay. We may yet be a ways from when it is common for a Sufi murshid to also be acknowledged as a Zen master, but I am sure that one song is being sung even today, and without a doubt, it is being sung here. Here, in this strange, troubled, conflicted, and wondrous country. This is what gives me hope.

What I am sure of is that the table has been set. And the conversations have begun. Christians and Jews, Muslims, and Hindus, Buddhists and humanists, and more, many, many more; were all at the table. And now we just need to look into each other’s hearts. I have no doubt as we do, we will see our place. And, with that we can find our hope. Hope. Hope.

So be it. Blessed be. And, amen.