Some notes for reflection.

I’m just back from our biennial gathering of Soto Zen clergy, filled with hope, some anxiety, and lots of energy for the project. Think renewal. And, with all that bubbling with comments on what is going on.

I’ve been thinking about the issue of formation of Soto Zen priests for some time, okay, decades. While I don’t have firm conclusions about this, I believe I have identified five separate styles for creating Soto Zen priests here in the West. Four of them I believe can legitimately use the term “formation” for how they approach the issue.

Each has as its base zazen, seated meditation, called shikantaza, or just sitting by our founder Eihei Dogen. This is the universal solvent for the matter of the human heart. But, I also hope it is obvious for leaders to need additional aspects to their formation. And the core of all these is the creation of a person immersed in the project, who sees with “Zen eyes,” if you will. Who is comfortable within the tradition and can transmit it with accuracy and skill.

The first approach is simply to go to Japan and enter one of the training monasteries. This is a powerful experience as testified by all who have undergone the discipline. It has been disparaged by many, including a few who have undergone it as “British boy’s Public School.” The approach is harsh enough that I do not think it can be transferred to the West. One is expected to fully conform to the flow of practice. It is brutal in its execution and I think would in fact be illegal in this country. Its shadow are broken people. But, it often actually does work – helping people to go beyond their ego obsession and see into a vastly larger world than we usually apprehend. When it works, and I believe it often does, it creates people of deep and wide sympathy for the world without easy entangling in the mess. And, I guess, we have to call this the gold standard for Soto Zen formation.

The second is the Western adaptation of monastic training. Here people go to one of the training monasteries that have formed around North America and undergo a monastic experience. The traditional system is to have terms, called ango, ninety-day stretches of intensive practice, punctuated by, often monthly sesshin, even more intensive practice periods, usually seven-days long each. Here the form is held a bit more loosely, in some ways more resembling Western Christian style monasticism – firm, but not at the level found in Japan. It’s shadow I would suggest is how seductive it can be, how people can fit into the rhythm and end up dreaming away their lives. But, for many it is that powerful transformative experience that orients the zazen practice and gives it the contours of a larger life. And I’ve known a number of people, a good number who have come out of this style of formation as generous hearts and wise counselors for people on the way.

The third is to have formation take place exclusively through retreats of three, five, and seven days, where one meditates for eight, nine, or ten hours. In my observation one sees definite changes at around a year of retreat practice that carries rough correspondence to what one finds from a monastic experience. And there are differences in the type of formation that are fairly easily noticed. These priests look different to the experienced eye, with less of a monastic embodiment. And with that the shadow is that they are dilettantes, their feet never held to the fire long and hard enough. However, at best they create a harmony of contemplation and engagement in the world that is powerful, and inviting. I’ve appreciated people formed in this way, although I admit often they seem to have a stance that is sufficiently different from the prior two styles of formation to give pause to those who find deep value in the former two.

The fourth adapts koan introspection, a discipline largely lost in Japanese Soto but through a couple of accidents of history relatively available in the West through the work of Daiun Harada at the turn of the last century, introducing a reform of one of the Japanese Rinzai koan curricula, adapting it to the sensibilities of the Soto style. This has mostly been expressed in lay lineages, but has a real presence among Soto clergy, as well. Together with the retreat system, this seems a model easily adapted to a culture where absences of ninety-day stretches can be untenable for sustaining work or family life, critical elements in our emerging Western Soto. Its shadow, to my observation, is a brittle form of insight, focused exclusively on the experience of insight, and divorced from the messiness of life. And, when it works, it is amazing and transformative in ways a bit different than the two monastic models, but definitely complementary. Here we see that image of “returning to the world with bliss bestowing hands.” This discipline is always, to my observation, associated with either the monastic or the retreat driven formation models. Using koan curricula as well as retreats seems, to my observation, to be an alternative to the monastic models that while it doesn’t completely map the early systems produces authentic Zen leaders. While I have a respect those two monastic models, and my own experience in the second of them, this combination of retreat and koan introspection is what I find most transferable into our culture and where I am committed to giving my time and energy.

The fifth is, to my mind, an aberration birthed out of a romancing of the rite of dharma transmission. It sees it as somehow in and of itself the point of Zen. Increasingly there are people who receive the formal seal but without significant preparation. Once in a while there are teachers of enormous quality among these folk, but the vast majority simply walk around looking like Zen priests. My anxiety for Zen in the West that the number of these folk is growing. (Based upon some comments on this posting at Facebook, I do want to add the additional complication of people who have come into the Zen world in this manner, but by virtue of ongoing practice, and what I’d call “continue education,” have folded back into what I think of as authentic Zen teachers…) No doubt life is messy. But that said, as I said, a troubling phenomenon…

As said, some notes for reflection.

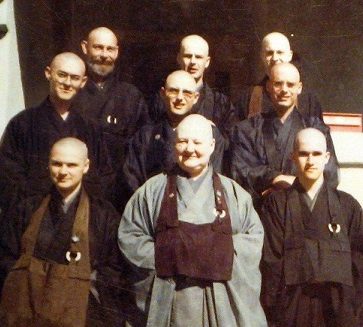

(And for those interested the photo was taken on the occasion my my shukke tokudo, on July 5, 1970. My preceptor, the Venerable Houn Jiyu Kennett is in the front in the center, I am in the middle row on the left.)