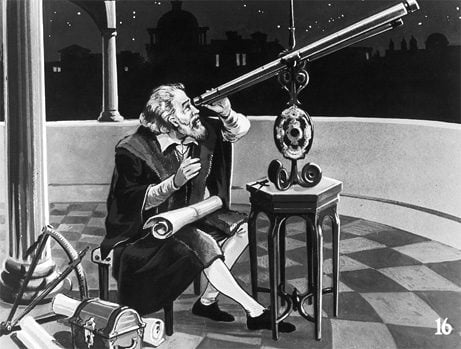

Toward the end of the year 1609 Galileo Galilei, who had been tinkering with lenses and telescopes for a while was able to improve one to a 20x magnification.

He promptly turned this vastly superior telescope toward the skies. In a letter he wrote dated today, the 7th of January, 1610, he stated he had discovered three new celestial objects near Jupiter. In another day he found one more. At first he believed they were stars. But, he quickly figured out they were in fact moons circling Jupiter.

He seems to be the first human being to make this observation, although there is some possibility the Chinese astronomer Gan De observed the largest of these, Ganymede, in 362 before our common era. It is physically possible to see it with the naked eye, but only under the most optimal of circumstances. While, with the aid of his wonderful telescope Galileo was able to show the moons to anyone who wished to look through the glass. And, I think while Gan De deserves his footnote, it is Galileo who deserves the main credit for his powerful discovery.

And, critically, the most important part of that discovery need not be shared. Galileo was able to note these celestial objects moved and were in fact moons for another planet. With this the whole idea of the earth as the center of things began to crumble.

For me the really important thing to notice within the emerging scientific method was a deep curiosity, a desire to know that birthed out of realizing one does not know. Something magical occurs within the human mind in that confluence of noticing one does not know, and opening one’s self to discovery. It can be summarized as “not knowing.” Even more important than Galileo’s wonderful telescope this not knowing is the critical tool of scientific investigation.

Me, I have spent a life time committed to spiritual inquiry. And what I’ve noticed is that there is within all the glorious mess that is religion a similar tool. Now religion serves many functions, but probably its primary one has been to sustain and transmit culture, and that is a naturally conservative thing, not particularly supportive of any rocking of any boats. We need only recall what happened to Galileo and who did it. But, also, there are those who desire to dig to the heart of the matter, and with that they bring a similar deep curiosity. And, this is also very much a part of religion.

The religion that has best presented this not knowing as a technology is the Zen school of Buddhism. Now, spirituality is not science, and its stock in trade is not a telescope or other physical device. It is concerned with the functions of mind, and its tools are the tools of the mind – observation and metaphor. And, so, it is a path filled with stories.

And the way of not knowing as a spiritual discipline is first presented as a founding story of the Zen school. It tells of an Indian prince who becomes a monk who succeeded to a line of transmission that traced directly back twenty-eight generations to Gautama Siddhartha, the Buddha of history.

Sometime early in the sixth century he decided to bring the great way to China and undertakes the indignities, difficulties, and dangers of traveling the Silk Road and finally makes his way to the Chinese imperial capital. His name was Bodhidharma.

Bodhidharma was granted an interview with the Emperor Wu of Liang. The emperor was a great supporter of Buddhism, and in response to his embracing of the Way, prohibited animal sacrifice and abolished capital punishment except for all but the most extreme crimes. He had even done a little suppressing of Daoism as a rival tradition. But mostly his work was positive. He had founded universities, expanded access to the Confucian civil service exam, and endowed monasteries and convents.

So, the emperor was quite excited at the prospect of this encounter with such an eminent monk. When finally they came face to face the emperor launched into a list of his actions in support of the Buddha dharma. And it is a long list.

The emperor then shyly asked if the venerable monk had an opinion about the merit that he generated through these many acts. He was profoundly concerned with evil karma, its consequences, and how to dissipate its negative effects. Some time earlier he learned through diviners that his wife, the Empress Chi, who had died was suffering torments in the hell realms for her obsessive anger in life. This had led him to commission the Emperor Liang Jeweled Repentance text and accompanying ceremony to help save her and others from the hell realms.

And, of course, this wasn’t his only brush with the matter of karma and its expiation. There was an even more intimate reason. The emperor himself had accidentally ordered the execution of another famous monk, and the guilt and anxiety that instilled continued to haunt him. So, yes, he was obsessed with the problem, and his request was from the bottom on his heart.

All this hung in the air as the emperor asked his question.

And Bodhidharma replied, “No merit.”

This was shocking. First, he was addressing an emperor whose power was so great that even though there was a prohibition on capital punishment, it existed only by the emperor’s fiat and the emperor could in a fit of anger order the monk’s death, and it would take place instantly. Already had happened once.

Of course, there is that second thing, as well. There was a deep desire on the emperor’s part to really know the secret heart of the matter. He wanted an answer to the surface question, what about the cosmic scales and what I’ve done to harmonize life? But, also, of course, that question carried the deeper question, as well. What about me? Who am I? What becomes of me?

And to all these questions Bodhidharma offers a negative. A no.

No.

No merit.

No. Merit.

No.

Not sure what should follow that disconcerting response, the emperor asks, “Who are you?” Again, the layers of the heart are all revealed. Who are you to dare to respond so disrespectfully? And, with that, the deepest question, as well. Who are you, really? Is there something special in that “no” that I should be attending to? Who are you? Really? Who are you?

To which Bodhidharma replied, “I do not know.”

Sometimes it is recounted simply as, “Don’t know,” and possibly the best translation is “no knowing.” The “I” of the matter drowned away in the great sea of not knowing. But, I prefer to tell it with the “I don’t know.” The “I” remains if swept along in that sea, froth on the surface, depths below. As my Rasta friends say “I and I” found here as “Not I, not I,” or, just not knowing.

Not knowing. Don’t know. I don’t know. Only don’t know.

Perhaps the death of that other monk long before hung in the back his mind, of his heart. I suspect so. But there’s something more going on, even for the emperor. And he let the insulting monk leave the imperial presence.

Later he asked his spiritual advisor about this encounter, and was told, “Bodhidharma was the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, the manifestation of compassion in this world.” Feeling waves of shame at missing the opportunity, he was about to send some soldiers to find him and bring him back when his advisor said, “It’s too late. You can send armies, but you will not be able to bring him back.”

The moment presented. That moment is over.

Bodhidharma crossed the river and traveled up country, settling into a cave not far from the renowned Shaolin Temple. He sat there for nine years, facing a wall before a student appeared.

That’s the story.

The history, as is often the case with such things is much more murky. In the surviving literature the name Bodhidharma appears here and there. Someone called Bodhidharma, possibly a Persian, marveled at a great city. Another, maybe the same Bodhidharma, maybe not, wrote a treatise on the great way. Bits and pieces. Here and there. Bodhidharma is a will o the wisp, appearing in mists whispering something, but, what exactly isn’t clear. But, not knowing is like that, isn’t it? More like a dream. More something appearing in the corner of the eye. You can’t quite capture it, but you can’t see it at all straight on. Not knowing is forgetting. Not knowing is losing. The closest to a volitional act is for not knowing to be a letting go.

But really not knowing is a gift.

It is as powerful as a telescope.

More so.

It takes us to the very heart of the matter.

Opening ourselves as wide as the sky, we can discover the heart universe itself.

Well, that’s what I say.

The invitation isn’t to a pat answer from someone else. The invitation is for you to do your own looking. Find your own deep curiosity. Open yourself into the great not knowing.

And discover whatever moons might be flying by.