I find myself think about the Buddhist teaching of emptiness. A lot, actually. For me it is one of the central pointers on my journey of spirit. And, I know this has been true for many others, as well. And, there are an astonishing, at least astonishing to me number of ways people turn it into something other than what it is.

The most popular of these misunderstandings over the years is that it is an assertion of meaninglessness. Another perennial is that it is Emptiness with a capital “E,” some magic place where everything is made okay. In recent years I’ve found a couple of people who think of it as a magic box. You put what you want, whatever it is, to do something others might think immoral or merely self-serving, actually whatever you can imagine into the great Empty box, and it comes out the other end as: sure, you can do that, go there, you name it. It’s all okay after being washed through the Empty box.

Writing a lovely article on the subject of emptiness and its misunderstandings a few years back, Zen teacher Lewis Richmond cites Nagarjuna saying “Emptiness wrongly grasped is like picking up a poisonous snake by the wrong end.” He called that right. Emptiness is one of those real truths, and real truths are dangerous.

So, what is the real truth of emptiness? And, what might it mean for us who walk the Zen way? To start Emptiness is how we usually translate the Sanskrit word sunyata and its Pali cognate sunnata. That word sunyata, sunnata can also be translated as hollow. It can also be translated as boundless. And I find these helpful, particularly boundless.

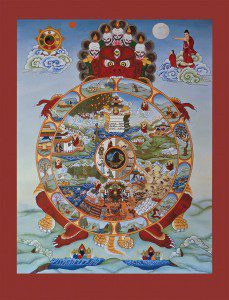

The term is a critical insight of the first strata of Buddhism and is inseparable from Gautama Siddhartha, the Buddha of history and his teachings. Describing this classical view the Theravada monk Thanissaro Bhikkhu tells us “emptiness is a mode of perception, a way of looking at experience. It adds nothing to, and takes nothing away from, the raw data of physical and mental events.” It is understand together with anatman (in Sanskrit and anatta in Pali) the assertion that there is no abiding or permanent self. So, if we don’t quite get that nothing has an abiding substance, we specifically are pointed to this critical point, you and I have no abiding substance.

As we unpack this, we see empty or, again, maybe hollow, or, maybe boundless, doesn’t mean we’re unreal, it means we are the product of a moment in time and space, the confluence of many events. And with that as everything flows, as the confluence continues in its motion, the thing we think of as “me” or “I” disrupts and is gone, leaving only the trace of our actions, which includes in Buddhism our intentions, a subtlety important to note, living on in new people or things.

But here’s the problem. We humans have a tendency to reification; that is we seem to have an inbuilt inclination to create that sense of substance, which proves to be so useful in so many ways, and then to make what is always in fact dynamic, concrete. We come by this honestly enough. It is simply a side effect of our necessary ability to slice and dice, to take things apart in our minds, and put them back together. This allows us to project to the future, and that together with our opposable thumb pretty much puts us in the driver’s seat on this planet.

As a matter of a lived spirituality, this is a critical encounter on the Zen way. The Zen teacher Brad Warner describes that additional nuance nicely, I feel, when he says, “Emptiness in Buddhists terms doesn’t mean nothingness. It means that every single thing we encounter – including ourselves – goes beyond our ability to conceive of it. We call it emptiness because nothing can ever explain it. Reality itself is emptiness because we can’t possibly fit it into our minds.”

Now, we need to be particularly careful here. It is past easy to assume that “more” is finally that true core, that ultimate substance, the part of us that is the divine or God. This, I’m sure is not what Brad means. And its not why I like that sentence. Looking for substance or essence or ultimacy in the “more” missing it, and missing it by the proverbial mile. That more is our intimate realization that the boundaries of our lives, for instance our skins, are absolutely real and true. But. The “but” of this is that it is a convenient, a useful demarcation. However, while useful, it is a useful construct. We don’t end at our skins. In fact there is no place we are not connected, that our lives, and our actions, do not touch.

There are all sorts of ways into this insight. And it certainly isn’t exclusively a Buddhist property. And, over the years, I’ve found these other gates helpful. Perhaps you might, too. So, Hermes Trismegistus, for instance, tells us “God is an infinite sphere, the center of which is everywhere, the circumference nowhere.”

And Pascal plays off of this when he writes, “The whole visible world is only an imperceptible atom in the ample bosom of nature. No idea approaches it. We may enlarge our conceptions beyond all imaginable space; we only produce atoms in comparison with the reality of things. It is an infinite sphere, the center of which is everywhere, the circumference nowhere. In short, it is the greatest sensible mark of the almighty power of God that imagination loses itself in that thought.”

Again, with caveats warning about taking that really useful term “God” and resisting reifying. Reifying is the problem. As a footnote to a footnote, I sometimes think the word God can be translated as boundless, as well. Whatever, if we take it, empty, hollow, boundless of God as the mysterious experience of the whole we’re on track. Here we find an invitation into who we really are as we really are.

Beyond the snares. Boundless. Beyond dreams of despair. The dance of the real. Beyond all excuses. Our true home.