The Buddha and the Non Believer

A Meditation on a Zen Koan

James Ishmael Ford

Blue Cliff Zen Sangha, Boundless Way Zen West

The Case:

A non-believer opened his heart to the Buddha, saying, “I am not asking about words, I am not asking about the wordless.”

The world honored one sat quietly.

The non-believer replied to this, “With your wisdom and heart you have parted the clouds of my confusions, and showed me the way through.”

He made bows and departed.

After this the Buddha’s attendant Ananda asked, “What did the non-believer realize?”

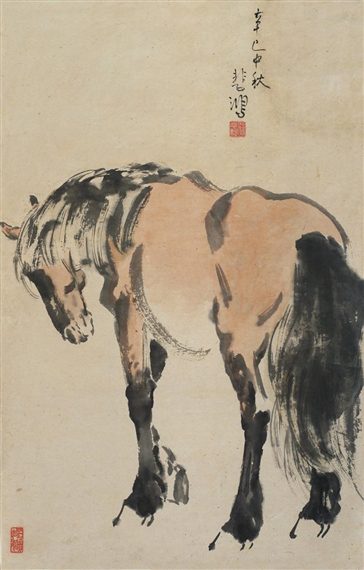

The world honored one replied, “He is like a fine horse that races at even the shadow of a whip.”

This anecdote appears in two classic Zen anthologies, the Gateless Gate as case 32 and in the Blue Cliff Records as case 65.

In the principal koan anthologies the Buddha appears about ten times. As he is representing in these anecdotes the fully developed spirit of the Zen traditions and these accounts don’t appear in the earlier collections of the Buddha and his teachings we can safely assume these are stories from the deep dream time of the Zen tradition. So, what are we to make of this? Well. first, and foremost, these stories are not meant to be taken as history. Rather, the important thing is that they point to your life, and mine. They are invitations into our own lives.

Understanding these are invitations into our own lives, there are two principal points in this koan. The first has to do with the Buddha and the non-believer. The second with the Buddha and Ananda, lovely Ananda, standing in for all of us, asking the question, “What did this mean? What is it all about.”

Now, its my experience that the ordering of koans often goes from the more important to the less important. This is a reversal of how we like to approach things within our culture. It leaves one with a sense of the anti-climax. So, for this reflection, let’s reverse it in our cultural style, and start with that conversation with Ananda.

What is it that allows someone not officially of the way to be received so approvingly by the Buddha? When asked the world honored one provides an analogy. It’s an old one, and actually occurs several times in the Pali canon which strives to capture the historic Buddha’s words. With what success is for another reflection. What we do know is that this image of a horse and the whip is an old one within Buddhism. Actually the metaphor appears throughout Buddhist literature, from the mouth of the Buddha in the Pali texts, to such Sanskrit Mahayana texts as the Lotus Sutra, to commentaries by Nagarjuna, and Dogen.

The worst sort of student has to be dragged to the water. In the analogy, given a good beating to grab the attention. The next sort needs a wack, but that will do. The next better you just rub the whip across the horses flank and it is ready to go. And, then, the finest horse, it just needs to see the whip. In the koan this is further conflated to a shadow of the whip. A hint, a breath, a pointing.

As an aside in his wonderful comments on this and other cases included in the Gateless Gate, the Chan teacher Guo Gu observes there is actually a fifth type, “a dead horse,” where it doesn’t matter what you do, they’re not going to respond. He cites a Chinese aphorism, “Don’t play music to a cow.” Someone does need to be ready to hear.

And not a lot of “koan” to it. More a comment on how we are, and something about being ready to notice the pointer, and then to look where it is pointing.

From there we can perhaps challenge ourselves to go to the heart of the matter, which we find in the actual encounter between the Buddha and that non-believer.

As the Soto commentator Tenkei Denson observed the non-believer’s question cuts “off both existence and nonexistence and not accepting annihilation or eternity.” Even more bluntly Hakuin Ekaku tells us “Neither yes nor no, neither ordinary mortal nor bodhisattva.” Here we see the non-believer has leapt beyond the traps of affirmation and negation. He, or, perhaps, she, is not caught up in the tangle, and that tells us, we’re encountering a mature traveler on the universal way.

He, or, again, perhaps she hasn’t accepted the dogmatics of Buddhism, perhaps not even the four noble truths. What this pilgrim of the way has seen is someone of great wisdom, and someone who might also has seen through the traps of form and emptiness. Hakuin puts his finger on the non-believer’s dilemma, “(H)having come to know as far as the place where affirmation and negation are one continuum, here he got stuck.”

I love that line about continuum. Here we are invited into our own intimate experience. For most of us the seeing separate is easy enough. You are you and I am I. Everything is separate. Going a bit farther down the line and seeing the connections, that’s harder. And, it is the project of the earlier parts of koan introspection. We need to see how we are one, or, even more accurately, how all things are empty. One. Empty.

I’ve known a number of people who get to this place. Sometimes they’re Zen people. Sometimes they’re not. The non-Zen people often find this place as One. But, that doesn’t matter all that much. One or empty are both themselves metaphors for something we experience. It is an insight, a seeing in. And this insight isn’t owned by a religion, it is a pointing to something true about the nature of reality, and specifically about our human minds and hearts.

But, so, we see it. Then what?

And here we find ourselves invited past the dream time to something mysterious and beautiful.

There are a hundred ways this can be encountered. But, one of the absolute best is what we find in this case, what we find in the Buddha’s silence.

Here that silence becomes a roaring stream, a rushing river, it carries us and all things forward. It reveals the heart of the great project, our seeing into who and what we truly are, and invites us from there into a dance, a dance of being.

Just this, as the masters say. Just this.

The painting “Standing Horse” is by Xu Beihong