According to Matthew Ciolek’s interesting Zen Calendar, today, the 5th of October, is celebrated as a festival in honor of Bodhidharma the semi-historical, semi-mythic founder of Chinese Zen (and some branches of martial arts, and the originator of tea in China…).

In the Zen tradition Bodhidharma, twenty-eighth heir in direct transmission from the Buddha Shakyamuni, is the great missionary carrying the Zen way into China in either the fifth or maybe the sixth centuries of our common era. There in that rich soil the tradition he taught took root and flourished, and in time would extend first to the countries within the orbit of Chinese influence and eventually from these to the West.

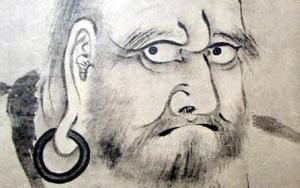

Called the Western Barbarian, Bodhidharma’s glowering eyes and red beard, so different from China’s other Zen teachers is easily identifiable, and just as easily he captures the imagination. For those of us informed by koan literature his image also peeks out at us through many different stories gathered in the major anthologies.

His encounter with the Emperor Wu is recorded as the first case of the Blue Cliff Record and the second in the Book of Serenity and in the Gateless Gate we have his encounter with his Chinese disciple and successor Dazu Huike.

For those of us familiar with the contours of contemporary scholarship, we know his historicity has been challenged by the main stream of the academic community. The facts of a living, breathing person hanging by a few slender threads, a Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang, the Further Biographies of Eminent Monks, and the prefatory material to a collection of teachings attributed to him, Two Entrances and Four Practices. It isn’t until the tenth century Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall, four or five centuries after his death that we even get the story we commonly know.

Let’s return to that Treatise on the Two Entrances and the Four Practices. I have. I’ve read it and reflected on it a number of times. It has been associated with Bodhidharma’s name since the second half of the seventh century. Some argue his disciple Huike compiled his teacher’s message as an early version the treatise. And then it was edited more or less into the document we have by the monk Tanlin. The earliest strata seems to date from about the sixth century. Possibly there are even earlier elements.

I find it interesting that the consensus view is that all other texts attributed to Bodhidharma date long after the old barbarian. But in this text with at least some possible connection to him we get critical Zen themes as “wall gazing,” “skillful means,” and “putting the mind at rest.”

Among the things that interest me about this document is how it stands in the place of our Zen tradition. The Dharma as we receive it in the Pali Sutras is highly didactic. The teachings are laid out in order, and each stage is spelled out. Within that received tradition the anecdotes of awakening turn on the Buddha explaining things clearly and people realizing the truth of his teaching.

Zen as we practice it, particularly within the koan introspection disciplines, plays out differently. Instead of lists and stages, stories are told. Sometimes with directions in them, but more often not, at least not in any normatively understood way. We are, instead, invited to look within our own hearts, into that rich but also desolate place, think of it as a jungle or a desert, or a deep frozen mountain range. And with the we are invited to take a journey. As we trek all along the way surprises, shocks, offense and joy erupt, pretty much unbidden, often at the strangest moments. And from those moments where we’re thrown into the mystery, we pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and find strangely, wondrously, that our lives take new courses.

And with Two Entrances, we see that from right at the beginning of Zen’s emergence. Although it is a hybrid document, representing the old and the new pretty jumbled up. In the treatise we start with an invitation to the leap from the hundred-foot pole, as we say in Zen. But, most of it is within that older more formal didactic expression of our heartful way. If you don’t push it too hard, the treatise is sort of a platypus, part mammal, part reptile, part classical Buddhist explanation, part Zen presentation. (You get to choose which is mammal, which is reptile.) All of it, I suggest, alive, and, for our purposes, useful.

That said the first two or three or four reads, I didn’t really like the treatise very much. As one friend pointed out, every paragraph is open to misunderstanding. Not to put too fine a point on it, it is possible to read the instructions to include “believe what you’re told,” “blame the victim,” “hate your life,” “don’t care,” and “give us money.”

I prefer the mature Zen version of Bodhidharma who we get in the first case of the Blue Cliff Record, with rough and ready encounters, direct pointing to the matter at hand and throughout a deep call to not knowing as the way to the end and the end, itself, surprises like volcanoes, bubbling, waiting to erupt into our lives.

Of course that’s all taste buds. In fact the invitation is really the same, classical or as the way of surprise, two ways to the same place. First we’re offered the Zen way in through the teachings themselves, as they are. Here, the great principle, the Dharma fully present, here, now.

Here we’re called to believe, not in the dead letter sense of affirming that which we know isn’t so, but rather as one old friend, Joan Richards says, believing as loving, belief as experience, belief as an act of surrender into something joyous and intimate. Not someone else’s experience, but yours, mine. Believer, lover, this is a dangerous path, no doubt. And it is good to check out that which you’re going to surrender your life into before going too far. It is surrendering our idea of separate selves as permanent and abiding things. And instead, it is opening ourselves as wide as the sky, and including it all as part of our interior landscape.

Which brings us back to that hundred-foot pole. In the Zen anthology the Gateless Gate, the forty-sixth case offers a commentary on all of this.

Master Shih-shuang asked, “How will you step forward form the top of a hundred-foot pole?” Commenting on this, another ancient master said, “Even though one who is sitting on the top of a hundred-foot pole has entered the way of awakening, it is not yet authentic. She must step forward from the top of the pole and manifest her whole body throughout the ten directions. He must step forward from the top of that pole and manifest his whole body throughout the ten directions.“

Just step off that hundred foot pole. This is the whole Zen project. We find it spelled out in the developed Zen way, but we see it, if kind of mixed up with other stuff, right there at the beginning, within the Two Entrances.

And if that is too hard, well, there’s another way that is the way, stages for the heart’s opening. It comes out of a contemplation of the classical teachings. And it’s a pretty clear roadmap. It involves paying close attention to the mysterious actions of karma not in our lives, but as our lives.

Personally, as someone who stands in the modernist camp, that doesn’t hold the need to believe in literal transmigration of lives, in contemplating the guidance found in the treatise, I’m delighted and informed to see how absolutely the doctrine works in this life of many lives.

Here we’re invited to surrender to the realities of the flux of events, and out of that to learn the dance of relationships, to see into the reality that we are, all of us, boundless, our essence is no essence at all, just openness, and from there to realize our lives just as they are, when not clung to, are the Dharma, the dharmakaya, the great open itself. No difference.

Step one, step two, step three, step four.

And then what?

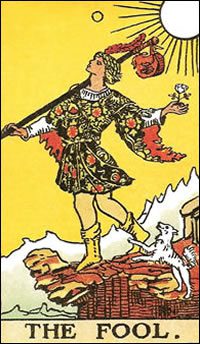

Like that Tarot card, with all the vigor and foolishness of youth, looking to the sky and stepping off the cliff. Like that person who has made it up to the top of the hundred-foot pole, only to discover there is still that next step, away from the pole. Off the cliff, away from the pole. Looking, not looking. No rules, or following the guidebook.

The invitation ultimately is one thing, breathing, living, inviting.

Just waiting your step…