How Christmas Became Christmas: A Meditation on The Evolution of a Holy Day

James Ishmael Ford

24 December 2017

Unitarian Universalist Church

Long Beach, California

Text

“There are many things from which I might have derived good, by which I have not profited, I dare say,’ returned the nephew. ‘Christmas among the rest. But I am sure I have always thought of Christmas time, when it has come round—apart from the veneration due to its sacred name and origin, if anything belonging to it can be apart from that—as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time; the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys. And therefore, uncle, though it has never put a scrap of gold or silver in my pocket, I believe that it has done me good, and will do me good; and I say, God bless it!”

Charles Dickens, “A Christmas Carol”

I don’t recall exactly, but a couple of years ago on one of the list servs that I belong to, I wish otherwise, but I’m pretty sure it was for Unitarian Universalist ministers, someone raised the question as to whether UUs observing Christmas was cultural appropriation.

I will not get into my complicated feelings about the whole concept of cultural appropriation, but I will say this is a pretty good example of someone not having a clue. The thought that this query might have been, okay, almost certainly was said by a ministerial colleague, makes me want to go take a nap.

We UUs have many admirable qualities. We see ourselves as fully a part of nature. And as rational creatures given the miracle of an opposable thumb we have special responsibilities in this world. So, we’re very much concerned with how we treat each other as well as how we live on this planet. We UUs also used to be of a scholarly turn. That part seems not so important to us anymore. For instance an ordained minister unaware of our connections to Christmas is lamentable.

Let me start out by saying no one in this country can lay a stronger claim to the modern concept of Christmas than Unitarian Universalists. And while that is true, and I will explain how in due course, Christmas, or at least central parts of that celebration are also ancient, much older than us, or even of Christianity. With that let me tell you a couple of stories, stories I hope you’ll see running a thread from the shades of antiquity right through to Long Beach, California, at the very tail end of the year 2017.

First off, Christmas as a midwinter celebration is actually ancient. I mean really ancient. These midwinter observances find their origins when human beings first noticed seasons, and specifically that days get shorter and things get colder. Then as we figured out how to calculate that moment when everything seems to be falling apart, but then mysteriously turns, we decided to help make sure that turning actually happened. Or, just in case it didn’t, to have one big party. Being of a practical turn in most cultures we did some kind of blending of those two things.

And so with that near universal background, on to the immediate predecessors of our actual Christmas. In that era we call Roman antiquity in the Mediterranean basin there were two particular festivals that are important for our story.

First, there was Saturnalia, a Roman festival in honor of the deity Saturn. It ran from the 17th of December right through the 23rd, featuring gift-giving, expressions of practical concern for the poor, general all around good-will, and a week-long party. Over time among some circles these parties took on elements of, well, orgy. By turns people celebrated and condemned this holiday.

And then in the early Christian era a newer cult emerged, that of the Unconquered Sun. At the dawn of the fourth century, the general Constantine was a devotee of that deity. Later as Emperor he converted to Christianity. Although, there are those who suggest he somewhat less converted to Christianity than took over the now increasingly powerful and potentially useful Christian church, while remaining pretty much still a devotee of that Unconquered Sun. We have a number of reasons to believe this might be so. Sunday, for instance, is a name he invented marking a weekly acknowledgment of the Unconquered Sun. And, coincidence or not, you can argue it both ways, December 25th was also the day of the annual festival in celebration of that Unconquered Sun.

Now, those concerned with when Jesus was born should note the Biblical evidence, scant as it is, in fact hints at his being born in the Spring. But, there’s nothing that confirms any actual date. The earliest record of a December 25th celebration of Jesus’ birth dates to 354, something less than twenty years after the Emperor Constantine’s death. And if you’re confused, in the neighborhood of 331 years after Jesus died. For those who like to quibble the split, meaning between the Western and Eastern churches, notes there are two different dates for Christmas. In the West our December 25h, but in the East, it’s January 6th, avoiding at least a bit, that unfortunate coincidence with the Unconquered Sun.

The coincidence of dates has been an awkwardness for Christians ever since the beginning. Now, there are legitimate arguments for a rough nine months out from the ancient marking of Mary’s annunciation and with it her pregnancy, which by tradition is observed on the 25th of March. Of course, this date has no documentary support. It looks like somebody invented it long after the actual events. And as I mentioned the Scriptures seem to describe his birth happening in the Spring.

The rather more important point is that the trappings of Saturnalia and the feast of the Unconquered Sun have pretty obviously been part and parcel of Christmas celebrations from the beginning. In fact, when the Puritans and Pilgrims made their way to America in order to be free to persecute others, one of the first things they did was deal with Christmas as the pagan holiday they clearly saw it clearly was.

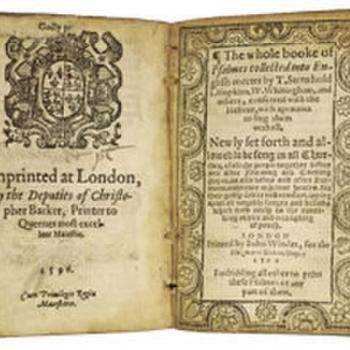

Here we get the actual war on Christmas. During the Reformation a minority of Protestants, including the Puritans, sought the abolition of Christmas as an egregious example of “popish idolatry.” They were clear the festival was a thinly Christianized celebration of the god Saturn. Or, maybe the Unconquered Sun. Same difference as far as they were concerned. And, so, come to New England, and finally in a position to impose their views on others, they did something about it. They made it illegal to observe Christmas. There were various bits of legislation. One was a 1659 law that made the observation of the holiday punishable by a fine of five shillings. I tried to figure out what that is in today’s dollars, but all I could confirm is that it was a stiff fine.

While these anti-Christmas laws were all repealed by the end of the Seventeenth century, Christmas was never in the years following a commonly celebrated holiday in New England. In fact it was considered weird. So, people like Anglicans when they arrived in the vicinity of Boston, were careful not to flaunt any vestiges of the holiday. Christmas was just an ordinary day.

Time passed, and then in the early decades of the Nineteenth century, a couple of things happened. Well lots of things happened. But, critically, the Unitarians emerged as a distinct spiritual perspective. They were open, curious, and profoundly humanistic in the same sense as we, their contemporary heirs do, of placing their primary concerns within this world, and within our lived lives.

Also, the center of intellectual exploration in the West at that time was Germany. And being of a scholarly turn, at least in those days, our early Nineteenth century Unitarian forbearers made frequent pilgrimages to Germany. Where they saw Christmas in full swing. And with all the vestiges of German antiquity and its dealing with deepest, darkest winter, including burning Yule logs and candle lit Christmas trees.

Then, as it happens, in the Christmas of 1832, the Unitarian minister Charles Follen is credited with erecting the first Christmas tree in New England. (Incidentally, also marked by a Puritan revolt, the Christmas tree appears to have not come to England until eight years later, in 1840, when Prince Albert put one up in Windsor Palace.) Back here Unitarians threw themselves into celebrating a holiday that seemed to perfectly suit that liberal and humanistic faith. In fact, in many ways early Unitarianism, still unequivocal in its Christianity, shifted the focus from Easter and the idea of a divine-other interceding in history through that mysterious and difficult and frankly unclear story of incarnation, death, and resurrection, and moved instead to a story of the birth of a child as the embodiment of our human hope in the face of gathering darkness.

But, that’s not the end of the story. Christmas in the English-speaking world has always been mixed up like that. And, the tilt has always been toward extravagance. In England, for instance, the Christmas season was marked as much by drunkenness and a hint of violence as anything else. And it wasn’t all that much better here. Then the next thing happened.

There’s a movie out right now, called the “Man Who Invented Christmas.” I had hoped to see it in anticipation of writing this sermon, but unfortunately, I was not able to. Doesn’t really matter, because I know the basics of the real story upon which the movie, good, bad, or indifferent might be, presents. That inventor is Charles Dickens. And the invention was through his novella “A Christmas Carol.”

It’s quite the story. It certainly pulls out all the stops. It’s sentimental, it’s schmaltzy, and it drives right to the heart of a reason for Christmas that makes all the sense in the world. It birthed into an English-speaking world that the author gave his name to. “Dickensian,” a time of horrendous social inequity, of extreme wealth resting upon a world poverty and social injustice larding through everything. Like, well, like a lot things we might recognize. The story challenged people. And it actually shifted how people in the English-speaking world approached Christmas. And, for many, their own spirituality, and out of that how they saw themselves engaging the world.

Dickens was a child of poverty, and he never forgot it. His writings and actions in life show his abiding concern for the fate of those lacking privilege. And this is critical for us. His thinking had a profoundly spiritual underpinning. While he was born Anglican and died within the warm embrace of that comprehensive faith, he also had more than a slight Unitarian connection.

One of his closest friends was the Unitarian divine Edward Tagart. During Reverend Tagart’s tenure at Little Portland Street Chapel, Dickens was a member. A real member, even purchasing a pew. It was only after Tagart’s death that he drifted slowly back to Canterbury, although always remaining, it is pretty obvious, a religious liberal.

What is most intriguing for me as, frankly, as a Unitarian Universalist (okay, a Zen Buddhist Unitarian Universalist) is that Dickens wrote “A Christmas Carol” while attending the Little Portland Street’s Unitarian chapel. And I suggest Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” is run right through with the core sentiments of liberal faith.

This is the Christmas we’re invited to recall. All of it. It includes the ancient things. The fear, and the hope, and of course, the parties. But also, there’s Mr Dicken’s coalescing of it all. Christmas past, present, and, you bet, future. So, think of those messages of Christmas past. Those bonfires to recall the disappearing light. Christmas green. Saturn. The Unconquered Sun. Where are they for you? Which parts call to your heart? Where do you find warnings? There are many threads in this cloth.

Then, what about today, that here and now thing, the Christmas present thing? You know the gift of this moment. As Dickens reminded us, we’re invited into the doing. And there is so much to do. So much need, so much. Our task, each of us, is to find that one thing, or that small number of things, which we can do; and then to do it, to do them.

From the wisdom of your heart, to what does your heart call you to do with your hands? Christmas as a call to see the connections, and to act.

And, finally, we come to Christmas future, and for that to Christmas day, like Mary birthing hope into the world. And with that story of a miraculous birthing the question for each of us, pregnant as we are with many possibilities: Which future are you going to let birth into the world?

This is the message of our way. You do get to choose, or, at least you get to choose your part. So, out of all these lessons, which one is it going to be?

A question waiting. Like a dream. Like a child.

Like a revolution. Like Christmas itself.

Amen.