There are two Suzukis who stand large at the dawn of Zen breaking forth into North American culture.

The first is Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki, best known as D. T. Suzuki, a scholar, translator, and essayist, whose writings both directly and through the popularizations by his sometime disciple Alan Watts, first introduced many of the basic principles of Zen Buddhism to the American public.

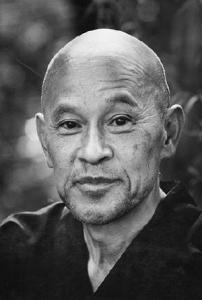

The other is Shunryu Suzuki, Soto Zen priest and missionary teacher who introduced Zen practices and established the first major Zen center in the West.

Shunryu Suzuki died on this day, the 4th of December, forty-six years ago. He was sixty-seven years old.

In Zen Buddhism as in much of Christianity great souls of the tradition are honored on the day of their death. For Christians it marks their entry into the heavenly reward. For Zen Buddhists it can mean a number of things, but for me, principally, it marks the fulness of a life.

And Shunryu Suzuki is one of our great souls, and the fulness of his life, filled with heartbreak and success, is one that has opened the Zen way for many. Including me. I count him as my first teacher. As do many. Many…

Shunryu Suzuki was born on the 18th of May, 1904, in a village about fifty miles from Tokyo. His father was the abbot of Shoganji, the local Soto Zen temple. His mother was the daughter of a temple priest.

He began formal Zen study at the age of twelve with So-on Suzuki, a successor to and adoptive son of his father, at Zounin temple in Mori. At thirteen he was ordained unsui, a clouds and water priest. When his teacher moved to another temple Rinsoin, Suzuki followed him. At fifteen he returned to his father’s temple. At this time Suzuki began to study English. This would become a life-long interest of his. Later he continued his formal training with the master Dojun Kato at Kenkoin in Shizuoka. He attended Komazawa University, studying Buddhism and English. At twenty-two he received Dharma transmission from his teacher. However he continued his training entering Eiheiji, one of the two mother temples of the Soto school in Japan. He later also studied at Sojiji, the other of the two mother temples.

During the war many Zen priests supported the war effort much to the embarrassment of their later Western disciples. Suzuki’s involvement is unclear, but it does seem he was involved in at least some anti-war activities. This marked him out as unusual, and probably meant he would not advance in the hierarchy. And in fact Suzuki served primarily as a country priest.

Throughout these years his interest in the West continued. Finally in 1959 Suzuki accepted an offer to become priest at Sokoji, a temple in San Francisco that served the Japanese and Japanese-descent community.

The Beat generation was in full swing and people were first learning there was such a thing as Zen. And they started coming to visit the temple asking for instruction. He invited them to sit with him early in the morning.

And with that what would become the San Francisco Zen Center complex began.

It is not possible to overstate Suzuki Roshi’s importance in the establishment of Zen in the West. If you want to learn more about him, his biographer David Chadwick maintains an amazing archive at Cuke.com.

My own beginning Zen practice was fostered by his centers. My first instruction was at Sokoji, and my practice began at a branch of the Zen Center complex, what was then called the Berkeley Zendo.

And, I am only one of thousands his work touched.

He left two dharma successors, his son Hoitsu Suzuki and an American Richard Baker. Through them the largest stream of American Soto Zen begins.

Many bows, great teacher. Endless bows…