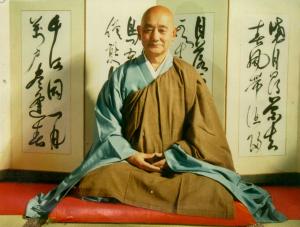

Daisetsu Tangen Harada Roshi, master of Bukkokuji Soto Zen Buddhist training monastery in Obama, Japan, died on the 12th of March, 2018. He was called by most of those who knew him Roshi-sama, which I think can be translated closely enough as “Beloved master.”

Harada Roshi was ninety-three. He was a successor to the great Daiun Sogaku Harada, the source of a Soto reformed koan curriculum and the leader of a revitalization of koan introspection within the Soto school.

As samples of his teaching, the text of an interview with the master and translations of two of his dharma talks. All are translated by Belenda Attaway Yamakawa.

Awaken to the True Self’

An interview with Harada Tangen Roshi 1)

Like a Chair

It was when I was seventeen years old. I had the good fortune to read a book called Inshitsu-roku, by Professor Enryohan, a noted scholar of the Ming Dynasty. This is a book of instruction which the professor compiled for his son, Tenkei.

The term ‘inshitsu’ means to be decided without one’s being aware of it. That is to say that the fortunes – sunshine and shadow, ups and downs – wich befall a person are naturally determined, without his knowing it, by his own past actions, virtue and vice.

Upon carefully reading this book, it became clear to me that there is a path to be followed, and I resolved then to follow that path.

According to the book, Professor En first came to deeply believe in karmic retribution through a fortune-teller named Ko. He then met with Zen Master Unkoku who impressed upon him that karma is only one side of the picture, Thus he writes his son, Tenkei, that one can take responsibility for the construction of his own world. It is not a matter of living out one’s life wedged into a predetermined mold, but rather, by virtue of one’s own efforts, it is possible to move, if even just a step, closer toward one’s aim.

From childhood on, as though in search of something, I was always a rather rebellious youth. In junior high school, I kept thinking that I had never really been given the opportunity to understand the reason for living.

I did not much care for Buddhist priests. I had the preconceived idea that they wore funny clothes, talked a lot of nonsense, and led lives of comfort and ease. But this book really addressed itself to that ‘something’ I had been searching for since childhood, and it surprised me to realize that the lesson came through a priest. Although Inshitsu-roku is at heart Confucian, not Buddhist, it is a Zen master who clearly points the way. And, incidentally, the man who translated the book, Harada Sogaku Roshi , was to become, five years later, my Zen teacher.

When I was eighteen or nineteen years old, I resolved to become like a chair. That was because a chair doesn’t refuse its services to anybody; it just takes care of the sitter and lets him rest his legs. After it has served its purpose, no one gets up and thanks or offers words of kindness to the chair. It will more likely get kicked out of the way. What’s more, the chair doesn’t grumble or complain or bear a grudge, but just takes whatever is given. When there is a job to be done, it puts forth all its energy without picking and choosing according to its desires. I was thinking, “wouldn’t it be great tohave such a heart.”

I wrote on a big sheet of paper, “Be like a chair”, and everyday took note of how-close I came. If even a little dissatisfaction arose, I would regard that as an embarrassing state of mind for a chair. I considered how thoroughly I was of use to others. A chair doesn’t plop itself down on top of the sitter, right?

What was positive about all this was that, if I possibly could, I wanted to put others before myself. The endeavor was not at all forced or unnatural; it arose from life itself and was enjoyable, not painful.

During the time I was following this practice, I went to climb Mount Kinpoku, a rather small mountain of the Jukkoku Pass at Yugawara. As I climbed that day, I could think of nothing but my own selfishness. Shedding tears, I repeatedly reflected and repented, “I’m no. good, I’m no good,” as I made the thirty minute ascent up the mountain trail.

There was a large stone statue on the flat crest of the mountain. If I saw it today, I might know what it is, but at that time I had no idea. Along the way there had been a number of figures of Kannon, so I think perhaps this statue was of Shakyamuni Buddha. But in those days I knew nothing of Buddhism or of paying homage to its founder. I had, however, committed to memory the rules of Professor Shoin Yoshida’s preparatory school 2) , and I began to chant those rules. Through chanting, I must have entered into a purer state of mind.

I crossed to the other side of the mountain, which formed a precipice. A valley had been gouged out below, and beyond the valley stretched the Pacific Ocean. To one side I could see the rolling hills of the Izu Peninsula. Transfixed by the mountain landscape, the wind blew into me from the valley floor, and I felt as if I were growing bigger and bigger.

In retrospect, we could say that I was experiencing the reality of being one with and cared for by all things of this world, experiencing the greatness of the life I have been given. But at the time, I just felt myself becoming bigger and the sensation of being protected by everyone. At that point I couldn’t contain myself anymore, so in a giant voice I shouted my name seven or eight times into the far-off horizon.

But I still couldn’t keep still, and suddenly I dashed off down the mountain path. Flying down a mountain trail is risky, but I made it back to Atami Station without tumbling into the valley below. It was as if I shot down in one breath. As nobody knew my state of mind at the time, if I had tripped and fallen down into the valley, everyone probably would have thought I had committed suicide. 3)

Although I felt at the time that I would often return to pay my respects to that dear, beloved mountain, I have not been back even once. 4)

Since that time, a bright and changed world unfolds before me. For one or two months after the experience, everything, down to the pebbles along the roadside, brilliantly glistened. It is an intimate, friendly life.

I remember well being filled with the knowledge of being together, part of the same life. At the time I still knew nothing of zazen and such, but the walls separating me from others had collapsed. My life had become a world somehow without discrimination, so I felt as if I could even chat with the chirping sparrows. Later, when I began to do zazen, I could receive the teachings of my master, which I had sought since childhood, with a ccmpletely open and receptive mind.

Without theoretical understanding and without being able to explain what happened, I had tapped into the very joy of life, and I determined from then on to dedicate my life to repaying my gratitude. As it was wartime, I felt that the one thing I could do immediately to help was to go first before the bullet. Propelled by the spirit of helping others, I joined the army. 5)

I was quite willing from the beginning to die. Like everyone else at the time, I felt itwas only natural to give my life in the war cause. But although I repeatedly found myself in perilous situations, including one year as a prisoner of war, I always, mysteriously and narrowly, escaped.

From that time on, whether or not my actions were recognized or appreciated by those around rne, the feeling that I had to put all of my efforts into what I knew I had to do became stronger and stronger. Then, in Showa 21 (1946), I began Zen training as a layman, and in Showa 24 (1949), I was ordained as a priest.

What is Buddha

The single most fundamental point in the buddhist sutras is ‘taking refuge’, or ‘namu’ in Japanese. This taking refuge in the three treasures – buddha, dharma and sangha – forms the foundation for all the precepts. To receive the Triple Refuge is to enter into the world of buddha.

The Sanskrit term ‘namu’ and the Chinese term ‘kie’ both express the same spirit, and both terms mean to go back to your true home. To really go back home, in the spirit of ‘kie’, one must entrust oneself and let go of the body and mind that he has up to now called ‘me’. If that thing we refer to as ‘me’ exists, then ‘namu’ means to give it all up for the sake of truth. So ‘namu’ and ‘kie’ are the Sanskrit and Chinese expressions which mean to place one’s full reliance, body and soul, on buddha.

Now, when we chant, “Namu kie butsu” – “I take refuge in buddha” – what do we mean by ‘buddha’? What is buddha? This is the question the person practicing comes to feel he must answer for himself.

If we are not clearly aware of the reality of a buddha, an awakened being who has thoroughly cast off everything to the last, we cannot really let go ourselves. So the question is: who, or what, or in what form is buddha to be found?

First of all, is there really anything of truth in this world for which you could let go of everything? If such a truth really does exist, I would say that you could surrender everything for it. Going further, if this truth happens to be just the thing you are most seeking, then the more willingly you will let go of everything for it. Finally, we could say that what we most ardently wish for is to possess everything without exception, to have everything as one’s own. If this truth is just such an all-encompassing state in itself, then you wouldn’t hesitate to give up everything for it.

Our desires are not such that we can say, “Oh, just to right here will be plenty.” Desire being insatiable, we cannot be satisfied until we have it all, to the very last. Some gentle-mannered souls may act with reserve and declare that they have plenty. But should you ask them, “Is this really enough?”, they will likely answer, “Well, if possible, just a touch more.” However, if you know that regardless of what you seek, your every wish will be granted, you will be willing to lay down your whole self. If whatever you seek is yours, isn’t it correct to say that there is no loss?

If a child is asked to name the one thing that is of most value, he will answer that it is ‘life’. There is awareness of life. If there is a life which cannot be lost for all eternity, you would gladly give up everything for it. And then there is material wealth. If by simply wishing for something, it is provided, why should you hesitate to give up anything? Finally, if you know that you will be released from all restraints, to live in perfect freedom, I would say it is all right to give up everything for that.

If these three conditions can be yours, I believe you will be ready to cast off your small self. We can say that that which is called ‘buddha’ is in itself the perfect embodiment of life, wealth and freedom. Eternal life as one’s own, complete freedom in everything, possession of all the truth of this world – if you know this is buddha, the heart which entrusts itself cannot help but well up.

Now, here

When you examine yourself, you find that something is missing. Or even if you feel fulfilled now, you are anxious that this contentment will be snatched away. You feel that you just have to find something more stable. At this time buddha’s existence cannot help but be revealed to you.

Although buddha mind is variously revealed through each individual’s own talents and gifts, buddha is now, here. But where is ‘here’? One master answered this question saying, “Help yourself to tea.” Another pointed ‘here’ when he commented, “What fine weather today.”

That which we most deeply yearn for is the thing that is already most fully present, already the very closest to us. Thus our ancestral teachers, according to their own circumstances at hand, have always shown that buddha is now, here. So we place our focus now, here.

While what you seek is really now and here, you habitually think of it as somewhere out there, outside yourself, so you search and search in vain. What you are looking for is already wholly and completely yours. There is nothing miserly about it; it knows no limits. You are the master of this life. When you sincerely take refuge (‘namu’) now and here, you will find yourself in what is most secure, in that which the heart most ardently yearns for – in pure, essential buddha nature.

‘Ichi Tantei’ practice

Perhaps you wonder if we do zazen in pursuit of that which we most want. No, we do not. Doing zazen is buddha. Doing zazen is already the full expression of buddha nature.

We are quickly caught up in the form of things, readily pulled in by what others have to say. This is such that if you are told, “Hey, doing zazen is buddha”, you might readily respond, “Yes, doing zazen is buddha, isn’t it?”

In that case, I will have to say, “No, you are wrong.”

At a gathering of Pure Land Buddhist adherents in a training center in Kyoto, the head priest delivered a sermon in which he said, “Just as it is, just this is salvation. Salvation is just this.”

A follower responded to this saying, “Just as it is, this is salvation, isn’t it?”

The priest answered, “You are mistaken,” and continued to expound the dharma,coming around again to say, “All right? Just as it is, this is salvation.”

Another participant repeated his words, “Just as it is, this is salvation, isn’t it?”

Wrong.

Everyone was off the track. The priest continued speaking. “Everyone has listened well. All right? Just as it is, this is salvation,” he reiterated.

At this, one believer in the audience shouted, “Thank you!” and made a deep prostratian.

The priest nodded broadly in response. “Good,” he said, and ended his talk.

In sum, if one grasps at this salvation, which is just as it is, he is already counter to its truth. Zazen is just like this. When one is doing zazen, a thing called ‘the self’ does not put in an appearance at all.

It is interesting to observe what a great discrepancy there is between theoretical understanding and truth itself. Take a dumpling, for example. Without actually sampling it, any explanation, regardless how thorough, would give only a rough idea of the flavor of that dumpling, but never its essential taste. Without actually chewing it, you cannot know its actual flavor. Depending on what we are eating, our individual way of tasting it may differ, I suppose, but the fact of having really experienced the taste is the same with everyone, isn’t it?

The reality of really tasting that dumpling is about the same regardless of whether you are eating it for the first time or if you are an old hand at eating dumplings. Zen is just like this. From the first time you sit, you can fully experience the flavor of zen.

For a thousand people who decide to sit, there are a thousand motives and wide disparity between depths of aspiration. The main thing, however is to awaken to one’s true self. This true self is supreme and irreplaceable, and we can call it ‘buddha’.

Of course one’s true self is not that which we ordinarily conjure up in our heads and habitually regard as ‘self’. It is, rather, the genuine self which cannot he grasped, seen or spoken of. So the main thing is just to become aware of this self.

We can speak of seasons in the process of coming to self knowledge, and we can say that opportunity ripens. There is the unawakened season, the season when one comes to know of the existence of this reality, the season when one believes in the teachings, the season when one believes and therefore mindfully keeps one’s awareness constant, and, finally, there is the season in which one is awakened.

We have the expression, ‘ichi tantei’. NOW. NOW. This is ‘ichi tantei’. A teacher is one who clearly reveals this to the student. “Reality is not off someplace else, away from right now and here. NOW. HERE. Don’t be careless. Don’t be off guard.” The teacher points out the path, the direct route, in the way most appropriate to each student. With this direction, the student can truly practice the most treasured, straight path.

To maintain this spirit of practice, the student single-mindedly works to make the ‘tantei’ constant so that everything is his daily life becomes this practice, this research into his true identity; everything becomes zazen. This is truly being alive.

When one settles into this ‘ichi tantei’, regardless of the job he has to do in this world, his efficiency increases manifold. This is because his practice becomes doing solely whatever he is doing, so that distractions do not arise. Therefore, in whatever circumstance he may find himself, his efficiency is increased.

It is such that he even comes to wonder how it is this world is taking such good care of him. Living in truth like this is wonderful!

Big mind, joyful mind, parental mind

Completely enveloped in and succored by the whole universe, you are like the mountains, like the seas, like the great sky which knows no limits. This great, big boundlessness is your own mind, ‘Big Mind’. To awaken to this Big Mind, just do whatever it is you are doing right this moment with your whole heart. If you do with all your might, this world will, without fail, reveal itself to you. This hard little lump of ‘self’ will dissolve, and you will inevitably awaken to Big Mind.

‘Joyful Mind’ is the mind that cannot help but feel gratitude. It is not that you feel thankful because you are supposed to feel thankful, but rarther that you cannot help but feel thankful. You feel so much gratitude that it spills over as joy.

And then from that boundless joy, kindness arises, kindness which is born from thoroughly exhausting all of one’s small self and merging to become one with others. This is ‘Parental Mind’.

When Big Mind, Joyful Mind and Parental Mind come together as one body, just this in itself is Bodhissatva Mind.

And isn’t this, indeed, the very basis of all education of our children? Shakyamuni Buddha and the patriarchs teach the fundamentals of education in this way. Each child is from the first the master of Big Mind. If this heart is encouraged to spring forth, the child will naturally become cheerful, and problems will take care of themselves. The child will become a human being who is sensitive to the pain of others. Sensitivity to others, joy which flows of itself – these functions of life itself are gradually cultivated.

No matter how much you study, how many books you read or how much theory you learn, this kind of knowledge can only be an aid, but never the driving force, toward peace of mind. And actually, if one is not careful, theoretical excercise can even be an obstacle. The important thing is to let go of mind and body and take refuge in truth itself. It is a matter of pemitting yourself, all you can, to recognize truth, to sincerly live in the now, here which IS your life.

If you see only the differences between yourself and others, you feel easily irritated, overly sensitive. If you’re out to take care of just your own little self, guard your own little castle, protect your own separate existence in whatever way you can, it’ll all eventually just go under anyway, won’t it? So go back to the starting point, return to your true home, the home which is the same for every single being in this world. I want to see you awaken to your true self.

Footnotes

1. Partial script from a conversation with Harada Roshi at Bukkokuji by TakashiAoyama, published in the monthly, Kongetsu no Tera, July, 1984. All footnotes are by the translator, Belenda Attaway, with the Roshi’s permission.

2. Shoin Yoshida’s preparatory school attracted many of the brightest and mostidealistic youths of the later Tokugawa Era. Some of these students became greatpolitical leaders instrumental in the establishment of the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

3. When asked if this experience could properly be called ‘kensho’, the Roshi answered that it was not ‘kensho’, but could be called ‘kangi’. The word ‘kangi’ iscomposed of two characters, both of which mean “joy” or ‘happiness’. The Roshi described it, “Deep glad. Alive.”

When the apparent ease of this first experience, which occurred without going through any of the rigors of formal training, was pointed out, the Roshi explained that his childhood situation must have been an influential factor. His mother died when he was born, and he was not raised in the most favorable of family conditions . If one loses his mother, the very essence of protection for most children, he is bound to search for something he can truly depend upon. He had a deeply sad childhood and was always a particularly sensitive youth.

When it was mentioned that reading this interview might even be discouraging to those for whom such experiences might not come so easily, the Roshi chuckled and pointed out that this was just a friendly chat over tea and cakes and that whatever came out of it was not planned. The intensely hard training under various adverse conditions, including several years of critical illness, did not happen to come out.

4. The Roshi did return to mount Kinpoku subsequent to this interview. He paid a visit to the mountain on his sixtieth birthday, an especially important occasion in Japanese culture. When he returned to the temple, the Roshi most enthusiastically and merrily reported two things. One was his astonishment at how long it took him to make the climb this time as compared to that day some 42 years earlier. The other was his wonder at a beautiful flower he saw on the surrmit.

5. When asked if he would go to war now “propelled by the spirit of helping others,” the Roshi immediately answered, “No. I am definitely opposed to war.” After he began training, he said that he came to understand that all hurman beings are brothers and sisters, and “Even if you’re to be killed, you won’t kill another.”

The Sixth Day of Sesshin

a talk by Tangen Harada Roshi also translated by Belenda Attaway Yamakawa

All of Life

another talk by Tangen Harada Roshi translated by Belenda Attaway Yamakawa