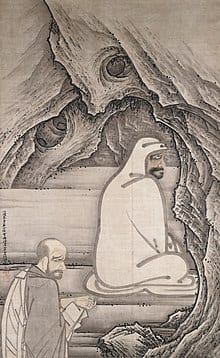

BODHIDHARMA SIGHED

Zen Comments on the Gateless Gate, Case 41

James Ishmael Ford

Let me tell you a story.

Once upon a time long ago and far away there was a virtuous woman and her husband. Life was good in nearly all ways. They had a lovely home, a farm that produced plenty of food, and even enough extra to sell, giving them opportunities to purchase small luxuries. All was fine. Except they had no children.

They prayed to the good gods for a child. But without success. Finally, they turned to the Awakened one. They offered incense and flowers and prayed for a child. They made donations to the support of the Awakened One’s community. Not long after, one morning at breakfast, they saw the inside of their house gradually grow light. It continued ever brighter, until it was impossible to see for the shining brightness. Strangely they were not afraid. Then, as suddenly as it arose, light passed away. And everything was normal again.

Not long after the woman knew she was pregnant. The couple decided when the child came, they would name it, boy or girl, Light. Nine months later their son, Light was born.

Light was an unusual child. He seemed completely uninterested in worldly matters. Instead he would wander into the nearby forest and climb up the mountain. He read the sacred texts of the intimate way and began to compose poetry.

When he came of age, he decided to formally inter the intimate way as a monastic. He went to Fragrant Mountain and entered the Dragon Gate monastery. There his hair was cut, and he took his vows. Light began by studying the sacred texts both those of the Elders and those of the Great Way. In time his renown as a scholar began to spread. But he knew something was missing. There continued to be a wound in his heart. Some sense things were wrong that no matter what he did, he could not shake off. He began to wander among the temples and monasteries speaking with various masters. And he spent increasing amounts of time alone in the mountains.

After several years of wandering, at the age of thirty-two he returned to Fragrant Mountain. There while deep in meditation a spirit appeared before him. It looked like an old nun, but he wasn’t sure. He could see her and right through her a the same time. She smiled gently at him, he could see the wall behind her smile, and said, “This is not where you will open your heart. Go south, my child.”

The spirit reminded him of his mother. Something about how its hair curled. Or, maybe it was that smile. At the same time Light was sure it was not her. Still. He felt the words were true. He told the master of Dragon Gate about his vision. The old monastic listened to the story, then ran her hand gently across Light’s shaved head, touching the seven unusal bumps that ran from his forehead and back. They reminded her of mountain peaks.

She said, “Go south, dear one. Head for the monastery of the Wooded Mountain. There you’ll find the master Bodhidharma. He will open your heart for you.”

The next day Light packed up what little he owned, a second robe, a thin blanket, a toothbrush, a razor, his bowls, and three books, and began to walk south. It was a hard journey. Things happened. At one encounter he thought he might die. But, he continued, and finally he arrived. At the monastery of the Wooded Mountain.

There Light was introduced to the master, who set him to the practices of intimacy. Light learned to sit quietly, present, noticing. He began his practice in earnest, sitting with a burning heart, seeking the secrets of the great matter. But instead of seeking trough books, or seeking by wandering in nature, he simply watched the currents of his mind. Light met regularly with his teacher. But, even with all this he couldn’t see through.

One day it all felt too much. His whole life seemed a waste. Desperate, he went to his master’s hut. But the door was closed. He knocked, but there was no answer. He felt a wave of panic. Of desperation. He knocked again, harder. And still there was no answer.

Not knowing what else to do. Not having any sense of somewhere else to go, he pounded and kicked the doorjamb. “Master!” Master!”

Finally the old teacher opened the door. “Yes?”

Light didn’t realize until that moment he was holding his razor. With a flash of the blade he cut his arm and bleeding, presented it to the teacher. “Please, please. My mind is afire. Please set my anxiety to rest.”

Watching his disciple holding his arm to staunch the bleeding while listening desperately for a turning word, Bodhidharma said to Light, “Bring me your mind, and I will set it to rest.”

Light wailed. “I have searched. Deeply. Broadly. With all my heart. But I cannot find any place where there is some thing I can actually call my mind. It is just thoughts and feelings arising and passing away. I find no one thing.”

Bodhidharma sighed. “Yes. Yes. That’s it. Knowing that, your mind is at rest.”

In the moment, Light understood.

There are other stories that follow. But this is the critical one. This is a story told from the mists of Zen’s foundations. It’s a koan, one of those questions that are not really, not exactly, questions. Rather they are dream moments that point us to our true heritage, to who and what we really are.

This stoy is captured in the Twelfth century anthology, the Gateless Gate, as case 41:

Our founding ancestor was facing the wall. When the student of the intimate way, Huike, standing in the snow, cut off his arm, presented it to the master, and said, “My mind is anxious. I beg you, teacher, please set it at rest!” Bodhidharma replied, “Bring me your mind, and I will set it to rest.” Huike wailed, “I have searched thoroughly, and I cannot find it.” The founding ancestor responded, “I have set it completely at rest for you.”

Our old teacher Robert Aitken tells us, “The anguish of Huike facing Bodhidharma is that anguish of the heroes and heroines of fairy stories and folktales who must strive constantly, practicing that which cannot be practiced, bearing the unbearable.” We are invited into a place that touches history, but is something more. There is a person, or, it seems likely there was a person named Dazu Huike, who in his childhood was called Light.

He was a scholar monk who lived in the sixth century of our common era. And somewhere around forty he became a disciple of the equally misty figure Bodhidharma. Huike studied with the semi-legendary founder of Zen in China for four years. Or, maybe it was five. A lot of people say six. And others like nine. Oh, and some say he lost that arm to bandits while on his pilgrimages.

History? Dream? Folk story? The details don’t really matter. What matters is that question.

And he has a question. It comes to him as anxiety. He feels it in his heart as a flutter. It hangs at the end of everything he does or thinks. Aitken Roshi, in his commentary on this case, tells us “This is a treasure of the Path disguised as sheer misery.” The roshi continues, suggesting “This treasure is found in all religions worthy of the name. It is the ‘dark night of the soul.”

As I speak these words we’re caught in the midst of a plague of sorts, a contagion that has swept across the globe. How bad it is, is not at all certain. But borders are closed. People are concerned, some maybe not enough, others, probably too much. This is a moment calling for measured actions, attention, and some care. A middle way, if you will.

Many, however, are tumbled into despair. How will I survive this? How do I get what I need? And hanging behind that is the great and hard truth: we are all going to die. We are all of us, every single one of us, passing as a morning’s dew.

And with that thought, or half thought, or, maybe it can’t even be articulated in a word, but is just a feeling. Anxiety. Anguish. A longing. Soldier’s when dying sometimes cry out for their mothers.

That cry.

For those of us committed to the intimate way, to finding our heart’s understanding, the quest we are on is like a thorn in our sides. And, if we persist, we sometimes discover it as a festering wound. Perhaps we know that cry for our mother. With that we stumble into that world the Christian mystic John of the Cross called a Dark Night of the Soul. He captured it in a poem. In Evelyn Underhill’s translation it begins:

In an obscure night

Fevered with love’s anxiety

(O hapless, happy plight!)

I went, none seeing me

Forth from my house, where all things quiet be.

Aitken Roshi tells us, “Huike had no choice but to enter this dark night.” Then he adds, “We have no choice either.” If we enter the spiritual way, the intimate way, and we give ourselves to this path, it will take us to this place. This is where our journey brings us.

It is the opening of our hearts into the mystery. But it starts hard. It is hard. It is a confrontation with our mortality. Actually, it is a confrontation with the mortality of the stars, as well. All things in fact do fall apart.

It is a dangerous moment. And we have to be careful. Here we need to engage our practice of presence and extend it from formal meditation into every single aspect of our lives, waking, working, everything.

And then there is the moment. It may come as a thief in the night. It may unfold like a flower blossom. There are as many ways as there are people.

The Roshi tell us “Bodhidharma said, ‘There, I have completely put it to rest for you.’” And he continues, “The rest that Bodhidharma confirmed in the heart-mind of his disciple is the same rest he sought to confirm in the heart-mind of Emperor Wu with his words, ‘I don’t know.’” That conversation which turns on not knowing is the very foundational story of the Zen way.

Here we’re invited into a new place. A spring from which life giving waters flow.

When we realize there is no source, that things arise and fall, and then we look yet deeper into that “no” of things, magic happens.

The world that was so tightly held, is set free.

The poet Lynn Ungar responded to the current pandemic with a poem. I find it speaks to this moment. Both this moment in history, and that moment in myth and dream that tumbles from confronting the dark nights…

What if you thought of it

as the Jews consider the Sabbath—

the most sacred of times?

Cease from travel.

Cease from buying and selling.

Give up, just for now,

on trying to make the world

different than it is.

Sing. Pray. Touch only those

to whom you commit your life.

Center down.

And when your body has become still,

reach out with your heart.

Know that we are connected

in ways that are terrifying and beautiful.

(You could hardly deny it now.)

Know that our lives

are in one another’s hands.

(Surely, that has come clear.)

Do not reach out your hands.

Reach out your heart.

Reach out your words.

Reach out all the tendrils

of compassion that move, invisibly,

where we cannot touch.

Promise this world your love–

for better or for worse,

in sickness and in health,

so long as we all shall live.

Now, in the Zen traditions we don’t usually describe it as reaching out, but rather allowing the world to come to us. But at some point it is no longer clear whether reaching out, or receiving. Within that moment of not knowing, there is a grace that brings all things together.

That said, that’s it.

That place. That moment.

Your hurts and mine, they don’t actually heal, but they join into something else. They are doors through which we walk. And when we walk through those doors we discover ourselves in a new world. Although it is at the very same time, just this world.

But the real has become magic.

And our lives are changed.

Here we find the rest that passes all understanding.

It becomes the mystery of not knowing.

Just this. Just this.