We have seen Yitzhak Perlman

Who walks the stage with braces on both legs,

On two crutches.

He takes his seat, unhinges the clasps of his legs,

Tucking one leg back, extending the other,

Laying down his crutches, placing the violin under his chin.

On one occasion one of his violin strings broke.

The audience grew silent but the violinist didn’t leave the stage.

He signaled the maestro, and the orchestra began its part.

The violinist played with power and intensity on only three strings.

With three strings, he modulated, changed, and

recomposed the piece in his head.

He retuned the strings to get different sounds,

turned them upward and downward.

The audience screamed delight,

applauded their appreciation.

Asked later how he had accomplished this feat,

the violinist answered

It is my task to make music with what remains.

A legacy mightier than a concert.

Make music with what remains.

Complete the song left for us to sing,

transcend the loss,

play it out with heart, soul, and might

with all remaining strength within us.

Harold Schulwies

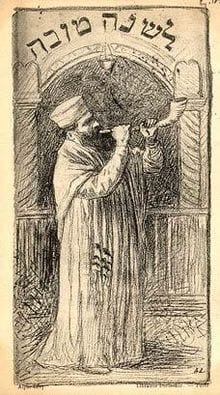

What follows I’ve adapted from earlier writings, an essay, and a sermon. I hope you find it useful on this 2020 Yom Kippur…

One of the more wonderful memories I have of our New England years was the time together with several friends Jan & I were at Tanglewood to see and hear Itzhak Perlman. Not only is he an astonishing musician, he is an inspirational figure. Small wonder he’s one of those people who by their being inspires stories.

For example that story in Rabbi Schulwies poetic telling.

Sadly, that story of Perlman losing one string while on stage, but continuing, adapting on the fly, and making a perfect whole, while lovely and inspiring, also never appears to have happened. Snopes, one of my favorite places to visit online, traces the story to a 2001 Houston Chronicle story, and reported its factuality “proved elusive…”

The first time anyone can find this story is in an inspirational book by Wayne Dosick. It goes:

“Childhood polio left Isaac Perlman able to walk only with braces on both legs and crutches. When Perlman plays at a concert, the journey from the wings to the center of the stage is long and slow. Yet, when he plays, his talent transcends any thought of physical challenge.”

That part is as true as is true. Jan and our friends and I witnessed that. But then the narrator goes on.

“Perlman was scheduled to play a difficult, challenging violin concerto. In the middle of the performance one of the strings on his violin snapped with a rifle-like popping noise that filled the entire auditorium. The orchestra immediately stopped playing and the audience held its collective breath. The assumption was he would have to put on his braces, pick up his crutches, and leave the stage. Either that or someone would have to come out with another string or replace the violin. After a brief pause, Perlman set his violin under his chin and signaled to the conductor to begin.”

Dosick tells how beautiful it was, and haunting, and how at the end Perlman said, “You know, sometimes it is the artist’s task to find out how much music you can still make with what you have left.”

Snopes spends a little time analyzing the Houston Chronicle story and shows it simply could not have happened as reported. More importantly, a bit of web searching on my part couldn’t find any word from Itzhak Perlman on the three strings event. So, until something new like that waiting statement from Mr Perlman I’m prepared to assume it was a fabrication by Rabbi Dosick.

Which opens for me a whole roomful of thoughts.

I tend to be a stickler for the facts. When something is attributed to a real person at a real time, well, it should be true. And I mean true in the very basic sense of existing within our shared reality, the one that we move around in, take nourishment from, communicate with one another in; you know, the one we live and die within. That reality…

Mark Twain once observed, “Get your facts first, then you can distort them as you please.”(Given the circumstances, I thought I better be sure Mr Clemens actually said this, and indeed, he did, in an interview with Rudyard Kipling, published in 1899.) So. Get your facts first; then you can distort them as you please.

What strikes me as important, however, and why I think this story gets told over and over again, is that while on the one hand it never happened, on the other hand it happens all the time, and is absolutely, completely, true. In this sense it reminds me of the deep truths contained in religious stories that are often, factually, at best unlikely.

So, do I think that on Yom Kippur God opens a book and writes down in it every person’s fate for the coming year? No. More importantly do I have to for it to be important, to point to a truth about me, and about the world of humanity? Again, no.

And out of those no’s comes a deep yes; a profound affirmation.

We are woven out of stories. Many are rooted in our fleshy history. Others are rooted in our fragility and aspiration. For me, Itzhak Perelman’s three strings story partakes directly from the source that feeds the great days of awe and culminates in the promise of atonement.

As our reflection is all about stories, here’s another one that I find constantly inspirational, pointing to the reality in the truth of Yom Kippur, and particularly the how of it all. Some years back I mentioned this essay “A Season in Hell,” writer Mark Dery’s account of his struggle with a horrific and rare cancer of the urethra.

I’ve known Mark for many decades, ever since he was an adolescent who hung out at the large used bookstore I worked at in San Diego. He and I have crossed paths over the many years, and Jan and I both consider him a friend, if one of those friends you only directly connect with under rare and odd alignments of the stars. Mark has gone on to become a prominent author and social critic, specializing in, as one review says, the “media, the visual landscape, fringe trends, and unpopular culture.” The boy I knew many years ago has become a very interesting man.

This essay is Mark laid bare, with all the wicked lightning fast wit, and a piercing eye that cannot miss any irony which presents itself. In that essay he cuts to something very near the bone, showing himself raw in the most extreme of circumstances. I recommend it to anyone who wishes to look unblinking at our humanity.

In the essay Mark wrote, “Recovering from major surgery, we’re helpless as newborns or nonagenarians, moved to tears by the kindness of strangers—or their casual cruelties. Some nurses are candidates for canonization; some missed their calling at Guantanamo. The night after my cancer surgery, I swam up to consciousness, in intensive care, woken by a woman screaming that her oxygen tubes had come loose, that she couldn’t breathe… She screamed and screamed, her voice rising to a ragged crescendo of terror.”

Once I had a brush with pneumonia. And with that I’ve experienced a hint of what this terror can be like. My own dreams haunted by the horrors of suffocation. Anyway, Mark continues.

“When no one came, other voices joined hers. A mass of punctures and pain, held together by sutures and butterfly stitches and Foley catheters, I added my hoarse yelp to the chorus of wails coming from nearby beds; every time I yelled, I felt something tearing inside. (Finally) In the fullness of time, a nurse materialized and, with the dead-eyed unconcern of sleep deprivation and empathy burn-out, plugged the woman’s oxygen tubes into her nostrils.”

I find it interesting and compelling that Mark quickly added, “Yet other nurses were ministering angels, changing my dressings and bringing me ice chips to suck on and tossing me throwaway kindnesses that, in the purgatorial grayness of a hospital day, felt like salvation.” That, too.

What I want to relate here is how in his worst situation, when that other patient was terrified and probably in genuine danger, and began her yelling for help, the other patients, including Mark, who could do nothing else, did what they could, they joined in her chorus of pain and fear and calling for help. Mark, even though he felt a tearing when he did it, yelled, too.

He did something. And, let me tell you, with that, a name was inscribed in the book of life by God himself.

I’m haunted this season by the Jewish calendar and directly connected with it, by the story of Itzhak Perlman and his three strings, and even more by Mark’s story of doing something. These are hard days in this world. You know it. And it is possible for us to feel drained and powerless. And yet. And yet. Within that and yet, I find a promise, the promise of our human condition.

I hope we take the truth in the story of the three strings and in Mark’s account of that calling for help, and remembering the days of awe, all of it, as an invitation. We are given an opportunity, to reflect on what has been going on, how we fit into it, what our individual actions mean, and with that for most of us, to do a little repenting, and perhaps, to recommit to our deeper aspirations, in the ancient religious language of the west, to atone. From here we can begin, again.

The great gift of our humanity.

There’s a delightful and compelling Hebrew term, Tikkun olam. It means, “healing the world.” This is the great project we can embark upon once we’ve seen the state of things as they are. This is the Yom Kippur promise. This is what makes these days of awe. We find this as a truth about ourselves, that we are broken, and that we are in fact about healing; then something mysterious and beautiful is birthed into the world.

It happens each time we notice. And it is a story worth telling and retelling.

Like three strings.

Like helpless in a hospital room, calling out for help for someone else.

The great story of our existence and of our possibility.

Days of Awe.