WHO SHALL WE BE?

A Meditation on Charles Dicken’s A Christmas Carol

James Ishmael Ford

Christmas Day, 2020

First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles

Today I find myself thinking of Charles Dickens and particularly his Christmas Carol.

Some of my friends actually read the original story, a few even aloud, annually. Others watch one of the many film versions. Me, I’m particularly fond of the Alastair Sim version from 1951.

Even the worst of them, the ones that play up the melodrama of it, looking simply to wring a tear from the viewer, also bring something powerfully compelling. The story itself has some deep truth within it. And the really good versions, well, they sing that deep truth into our hearts.

Charles Dickens was a child of poverty. That hard fact was something he never forgot. His writings, and often his actions in life, show his abiding concern for those not born to privilege, and especially those crushed by circumstances beyond their control.

A Christmas Carol casts a harsh light on the grasping and the casual cruelty that marks too much of the culture in 1843, when the book was published. And, truthfully, and part of why it is still relevant, so true of our culture 177 years later.

But it’s not just an indictment. At the same time that he holds up that mirror revealing harsh, harsh shadows, Charles Dickens offers us a way through.

While he was born Anglican and died within the warm embrace of that comprehensive faith, he also had a deep Unitarian connection. One of his closest friends was the Unitarian divine Edward Tagart. And during Reverend Tagart’s tenure at Little Portland Street’s Unitarian Chapel, Dickens’ regularly attended services. He even purchased a pew, which is equivalent today to joining a congregation. It was only after Tagart’s death that he drifted slowly back to Canterbury.

What is most intriguing for me is that Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol during those years while he was attending Little Portland Street’s chapel.

Here, today, in this gathering, I suggest Dickens’ Christmas Carol is run right through with the core sentiments of the liberal faith that enlivens this congregation. As he wrote of his years attending that chapel how good it was joining among people who practice charity and toleration. And how important that was for him.

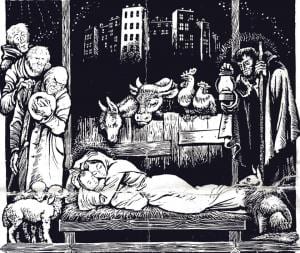

And. As wonderful as those things are, let me suggest there’s something more on offer here than charity and toleration. If we take a more intimate sense of the Christmas story, as something about the mess of our condition, expressed in the story of one poor child and that child’s parents, and with that human dreams of possibility, doors are thrown wide open.

Sophia Fahs sang what that can look like.

For so the children come

And so they have been coming.

Always in the same way they come

born of the seed of man and woman.

No angels herald their beginnings.

No prophets predict their future courses.

No wisemen see a star to show where to find the babe

that will save humankind.

Yet each night a child is born is a holy night,

Fathers and mothers —

sitting beside their children’s cribs

feel glory in the sight of a new life beginning.

They ask, “Where and how will this new life end?

Or will it ever end?”

Each night a child is born is a holy night —

A time for singing,

A time for wondering,

A time for worshipping.

And with that intimations of what might be. A north star for all of us. And a path into understanding the sacredness of our human condition, the sacredness of this very earth. It is a story of who we really are, and what we might be.

Now Dickens in his lived life fell short of his ideals. Like most of us. But that seeing into the connections, and doing justice, and loving mercy, and failing – but then trying again, and trying again, is at the heart of our human way. Just as Christmas rolls around every year offering a new chance, we too, are called again and again.

It’s Universalism. The way of love. Endlessly unfolding, forgiving, welcoming. Whoever we are, we are always welcome. Always angels whisper in our ears, Come, come. Our trespasses forgiven a hundred times a hundred. Come. Just come.

Here a light is being cast showing something. If we’re invited back, and I believe we are always invited back: how do we do it? How, given all the givens of who we are, how do we come back?

Which brings us to Dickens’ story and particularly those visits from those ghosts.

So, a question, an important one: Who is Marley in your life? With whom have you conspired to sell your heart to something less than love and care for others? And with that finding your true heart and maybe even saving yourself? Who do you know who has fallen and in that fall has given you a terrible gift: a warning?

A hard question. And a door.

Then, within that vulnerable moment we might find how are invited to the lessons our ancestors gave us. More doors. As one friend told me, when asked how it was she could find time in her busy life to stop and work at a food pantry, one not all that different than the one that operates out of First Unitarian here in Los Angeles. she replied, simply, clearly from this place to which we are called today: “Because,” she said, “My mother taught me to.” We are surrounded by clouds of witnesses. Our anestors whisper in our ears. What are the lessons you know are right, that you learned so long ago, but perhaps in the messiness of our lived lives have forgotten?

Today we’re invited to recall, to recollect those messages of warning, of hope, and of guidance.

So those messages of Christmas past. Where are they for you? Which ones call to your heart? Do they come from religion, from literature, from your life? Or, in differing measure, from all? Have you reflected on what they might mean for you?

Then, what about today, that here and now thing, the Christmas present thing? You know the gift of this moment. The invitation within our tradition is to come into the doing, to recall we are verbs much more than we are nouns.

As Dickens reminded us, as this day reminds us, we’re invited into the doing. And there is so much to do. So much need, so much. Our task, each of us, is to find that one thing, or that small number of things, which we can do; and then to do it, to do them.

I think of all who need. I think of us. Another gift of questions follow. Who serves and who is served? Who is guest? And who is host?

And, with that, finally, we come to Christmas future, and for that to Christmas day. As with that story of a miraculous birthing the question for each of us, pregnant as we are with many possibilities: Which future are you going to let birth into the world?

You do get to choose. Or, more correctly, at least you get to choose your part. So, out of all these lessons, which one is it going to be?

What will be your gift to this world?

There are many paths we can walk. This New Year coming is filled with dangerous things and wonderful possibilities, fool’s gold, and pearls of great price. What will you reach for? Where does your heart guide you? From Christmas day, where do you wish to go?

And with that a wonderful and terrible question. Who shall you be? Who shall we be?

Finally, my hope for all of us this Christmas Day is that the ghosts of our hearts guide us to the true spirit of Christmas, the spirit that informed the writing of a Christmas Carol – to a life of love and care and out of that, a life of doing.

This is the miracle: Knowing who we really are, all of us relatives: we are the holy family. And knowing that, striving to create a world where no one is left behind, all are carried together.

This is a blessing for our own hearts, a turning from wherever we were unconsciously going, to a life of possibility and care.

To a life engaged with the great family.

Living into the Christmas spirit.

Born like a child in a manger. No one knows what will come of that small birth.

But the possibilities; oh, the possibilities.

Amen.

Amen, my friends.