Every once in a while I feel it important to pause and to assess where my heart is, what I believe, what guides me, what sustains me, and what pushes me forward. Hoping, possibly, this current edition of my confession might be of some small help to others on the intimate way.

My Confession.

James Ishmael Ford

When I was a youth I wanted to know God. Desperately. With all my heart. I even prayed that if God would reveal himself, herself, itself, in the next moment he, she, it could kill me. What I got was silence.

At some point I realized there was motion within the silence. And I began to probe into what that might be. At the same time I was also profoundly aware of hurt. My own at first. But, soon, I noticed it all too common among humans. Everywhere I looked this hurt.

As I turned from adolescent toward adulthood, I continued to be driven by an investigation into the hurt, and the fears and hopes I invested in that word God. I found I could locate much of this dis-ease as existing inside of me. However, I was also, as I said, increasingly aware of the hurt around me.

First, thanks to the civil rights movement I began to see how unjust our country was in its treatment of racial minorities, most especially those of African descent. And, in my time and place, the rise of women’s consciousness and a new women’s liberation movement challenged all sorts of things I just assumed. And, slowly I noticed the injustice of the treatment of sexual minorities. The mistreatment of our planet and how fragile it all is gradually began to seep into my heart. What I saw, I began to notice, was the power and danger of tribalisms, of our seeing an us and a not us.

Then. At one point I hitchhiked into Mexico. Among the wonders, I was most touched by poverty, especially as I saw it in the cities. Beggars. Especially in Mexico City, a tiny indigenous woman with a baby begging on the sidewalk.

I felt I saw Mary and her babe.

Us and not us, me and not me became shaky.

I gave her all my money. I then went into a nearby church and cried.

Then I had the privilege then of calling my parents and asking for enough money to come home. We were poor by American standards. But they could and did buy me an airline ticket and sent some cash.

Home. Home.

So much hurt. Mine. And that of this world. And in the midst of it some holiness calling.

My childhood version of my childhood religion didn’t work. I flirted with Vedanta. I entered a Zen Buddhist monastery for a time, and was ordained. I danced with Sufis. I explored some of the rituals of Christianity. I joined a Unitarian Universalist church, and later was ordained.

For forty years I’ve been a Zen Buddhist and Unitarian Universalist, deeply committed to what each offered, and invited, walking the liminal space between.

I guess my view fits broadly into the spiritual category called nondual. In Zen we would say not one, not two. But with a lot going on between those two poles of not. I learned to value traditions, but to be suspicious of their shadows. Yearning for personal freedom in my explorations, but noticing how for others, too free a wandering often led to disaster. It seemed to me the way was razor thin.

I looked for guidance.

Early on I embraced a naturalistic view of this world and the human condition, finding it to have the fewest internal contradictions. At the same time I try to be wary of facile reductionism that voices as bare materialism. Nonetheless I felt intuitively that I would be wise not to stray too far from the observations of the natural sciences in looking for anything that might be called “the real.” I sought an open mind, but one not so open my brain would fall out.

I noticed along the way that we humans know with a variety of faculties only partially captured by the Western frame of five senses. Buddhism helped to shake that up by counting six, the one’s we’re commonly aware of, but adding in as a sixth the human mind itself.

With that I’ve felt it wise to parse that knowing faculty itself into at least two parts. There is the rational, our ability to slice and dice, and predict. Quantitative appreciations, and what might be learned there. But, there is also a feeling part, a less clear, more ambiguous sense of things. Intuitive feels a right word, if it is engaged modestly. I guess qualitative appreciations, and what might be learned there.

All of it taken taken together is a sort of witnessing. A sort of not knowing. I was exploring something totally of this world. And. There seemed to be a lot in that and. What I saw was that when I’m lucky enough to avoid or drop my opinions, and remain curious, not knowing in the deeper way, things emerge.

I’ve come to speak of mind and heart for how we can engage these things that matter most, that touch on hurt and healing, both internal and within the world. In recent years I’ve come to feel heart is a better word for what I’m encountering. Standing in that place I find it messier, and with that, just a bit truer.

Similarly, I’ve also come to find the word soul helpful when considering this path I’m walking. Not soul as something that occupies my body and continues after my death, avoiding any essentializing of that which passes. Although within the mess I find there are layers which I only partially understand. So, always hesitations. For me soul is a perspective. It is about soulfulness. It comes with living in the heart space of my consciousness.

I also find God a useful term. I like how in Abrahamic traditions it seems to start out as a storm god, then becomes the god of a tribe, and eventually becomes the loving parent of all humanity. So obvious an example of projection. And, like with soul, it seems truer having many layers, some of which, frankly, offend common sense. This big word God also includes several thousand years of philosophical exploration and speculation. it becomes a unity. It becomes a trinity. It becomes absolute nothingness.

God is the hole into which I throw my hopes and fears. The whole within which I discover my hopes and fears and everything else are connected.

For me it becomes a pleroma. Pleroma is a term I lift and adapt from Christian gnosticism to stand for the great unfolding of the universe as things rise and fall, and without substance, and yet, are each and every part, a wonder and a mystery. In all its multiplicity, one thing.

Marking this out I draw my understanding of it from Buddhism.

My Buddhism.

For me the best religious analysis of our situation is found in three Buddhist terms: the four marks of existence, the two truths, and the three bodies of the buddha.

The first three of the marks are observations about the nature of things, and specifically with our human condition. 1) Everything is made of parts and they will inevitably come apart. 2) There is no abiding self. The self is real, but it is mutable, and in the end it is mortal. 3) The motion of things rising and falling is experienced by humans as painful, anxiousness, anguish. Taken together in some schools of Buddhism these are called the three marks of existence.

The fourth mark is an assertion that there is a way through the hurt. It belongs specifically to our human world. Given the size of the cosmos “human” here would be any creature with a consciousness that can discern the first three marks.

The two truths can be summarized as 1) the rising and falling thing of this universe and our human hearts in flux, and 2) the absolute emptiness of these rising and falling things. Humans naturally apprehend the first, while the second is recessive, and normally has to be sought out with the aid of practices of presence.

The three bodies of buddha describe how we encounter these things: 1) within history and that rising and falling of things. 2) as totally empty of substance. And, 3) a third place, of mystery, where the rising and falling feels less concrete, and more fluid. Dream and metaphor become the language of this body.

But, as wonderful as this is, I feel it doesn’t end there. I think of that indigenous woman, so tiny, and her child. Hungry.

And all this is not about lists. It isn’t about the finest analysis. Its about a hungry child. It’s about my restless heart.

It is not about turning away. It is about learning to hold with open hands. A bad metaphor, but I hope it points.

It is as Mary Oliver sings to us: “To live in this world, you must be able to do three things: to love what is mortal; to hold it against your bones knowing your own life depends on it; and, when the time comes to let it go, to let it go.”

I feel the tugs of our connections. While in some ultimate sense, touchable, but not a place we can live. It is boundless and open. ineffable. In my lived experience I found myself tied up with the rest of the world, and most especially with the rest of humanity. Bound within openness.

Those words call us to intimacy.

We are a caravan together, as intimate as intimate can be. And it is what we do together that makes it either a caravan of despair or of joy.

Here I find that most mysterious of stories the Exodus being totally a part of who I am, and how I see the world.

My Judaism.

My biblical studies lead me to understand there’s scant history in the Egyptian captivity and the Exodus. But sometimes it’s fiction that tells the truth closest to straight on. The the story in all its complexity is the story of our human liberation. We foolish and easily distracted, selfish, and yet constantly called and called again to a communal liberation is as true, to me, as true as the bones holding up my body.

Totally a fabrication, probably of captive Canaanites in Babylon dreaming Judaism into existence.

And. And. As true and true can be.

Every terrible word of it.

And I find this exodus story washed through Christianity especially touching my heart.

My Christianity is based on the teaching of a wandering sage, a wonder worker and a teller of stories of oppression and freedom. Maybe half mad on God. And uttering dreams. Dreams about healing inside and out. About a mysterious kingdom that is both within and among.

It seems to be about drawing together. About the intimate.

Dreaming into a mysterious story about who we are and how what we are is sacred down to the earth between our toes.

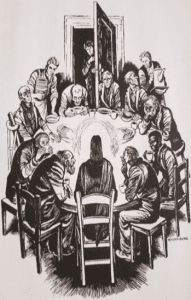

It boils down, for me, not to a cross, but into a meal. A meal where we are all invited, whoever we are.

All of us confronting the mystery in a meal, in a taste of rice, a taste of bread.

Ranking with the Exodus story, I am marked by the sayings of Jesus, and especially the Beatitudes. With more than a dash of Mary’s song, and its terrible justice.

Why? Why this?

Why Christianity and Buddhism? Or, more properly, I suspect, why Buddhism with a significant Christian flavor?

In some significant part these are the things I was born into, and then, by wondrous accident I stumbled on. Good fortune. Poets might say from the good karma of past lives.

Or. Just good luck.

What I can say out of this is that I think my prayer was answered. God revealed herself, himself, itself.

Found in the silent places of our hearts.

Found in sharing a taste of bread.

As natural as natural can be.

And yet, a wonder and a mystery.

My religion.