While Edward Bouverie Pusey died on the 16th of September in 1882, and that day is observed as a feast throughout much of the Anglican communion, the feast itself in observed here in America on this day, the 18th of September.

I noted this about six years ago. And what follows was largely written then. Although, while I continue to be charmed by the title and retain it, I have washed through the meditation lightly, to reflect those past six years.

I’ve always been fascinated with the High Church stream of Anglicanism. And, I must admit, I’ve always wondered why. My, as I like to think it, mature spirituality is pretty straight forward Mahayana Zen Buddhism. I find the insights articulated first by Gautama Siddhartha, the development of the four seals, the two truths insight, and the three bodies of the Buddha, as well as its manifestation within the Zen schools and particularly among the koan schools. That with a bit of a rational wash.

I remain endlessly grateful.

And yet Christianity still whispers into my heart.

My little summation that I have a physiology of faith probably expresses the contradictions as well as anything. I claim that Buddhist brain, Christian heart, and humanist stomach. The Buddhism is very much how I see the world. The humanist stomach, particularly the rational and this worldly sense of that is how I feel the world. But, I persist in dreaming the world through Christianity.

This probably explains in some ways my decades long association with Unitarian Universalism which allows me to be who I am and continue to explore where I need to.

That said, Professor Pusey…

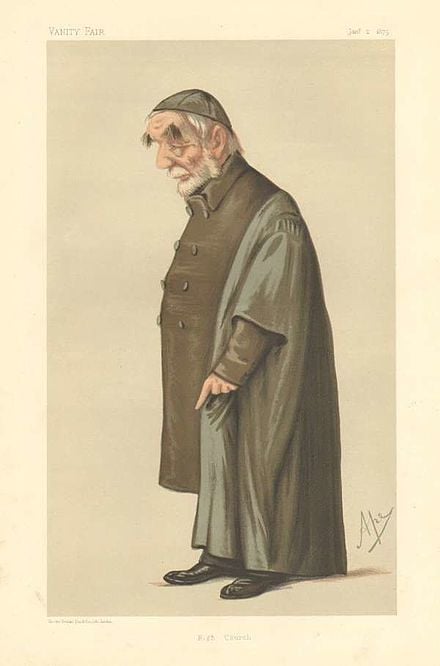

Edward Pusey, Regius Professor of Hebrew at Oxford, and canon of Christ Church, for those who don’t know, was the spiritual leader of the High Church revival within the Church of England in the middle of the nineteenth century. His ruminations on communion in particular helped to breath life into what some saw as a moribund tradition.

What I find particularly fun in re-reading about him in the Wikipedia article were two things. One the persistent assertion, particularly in his younger years that he was a rationalist, despite his sometimes not very convincing assertions otherwise, and a line in that Wikipedia article describing him as “more a theological antiquary than a theologian.”

That hinted to me at something of the attractions I have for the tradition. I do not believe in a deity outside the universe that breaks through time and space to turn the course of cause and effect. And with that the whole edifice of the Christian tradition collapses. But, the shell continues to hold my attention. As I wonder about it, I realize it is because the church itself is a repository of collective wisdom and intuitions about reality. The core story is not factual, but it allows our dreams of connection, our dreams of mutuality and responsibility expression as stories, and in that sense continues to be true.

And perhaps it is because of this that I find Anglicanism becoming a religion of story, of a way of life that can survive without belief in a literal God or, and I do consider this the more problematic thing, without belief in souls advancing to perdition or reward. In short it becomes a particularly attractive form of a liberal Christianity that points to how we can live and how we can die.

A new middle way…

A religion that could be…