The Ten Ox Herding Pictures (Chinese: shíniú 十牛 , Japanese: jūgyū 十牛図 , korean: sipwoo 십우) are a map of the spiritual journey within the Zen schools.

The earliest use of a bull or cow or ox as the self in practice seems to date to the Nikayas, the earliest strata of Buddhist teachings, and may have been used by the Buddha of history.

The earliest use of a series of images seems to date from the Zen schools in China in the eleventh century. At first a series of five pictures. But, these quickly mutated, and by the twelfth century a couple of series of ten became popular.

In the 12th century the Chinese Linji master Kuòān Shīyuǎn’s images and verses quickly became normative. Today when people think of the ten Oxherding pictures, it’s this series that is meant.

According to Wikipedia, “In Japan, Kuòān Shīyuǎn’s version gained a wide circulation, the earliest one probably belonging to the fifteenth century. They first became widely known in the West after their inclusion in the 1957 book, Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A Collection of Zen and Pre-Zen Writings, by Paul Reps and Nyogen Senzaki.”

The version copied below includes the translation of the verses by Senzaki and Reps. It also includes brief comments from Nyogen Senzaki, the scholar DT Suzuki, and the early American Zen teacher Philip Kapleau.

The images copied here are by Tokuriki Tomikichiro (1902-1999)

THE TEN OXHERDING PICTURES

One: Search for the Bull

In the pasture of this world, I endlessly push aside the tall grasses in search of the bull.

Following unnamed rivers, lost upon the interpenetrating paths of distant mountains,

My strength failing and my vitality exhausted, I cannot find the bull.

I only hear the locusts chirring through the forest at night.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: The bull never has been lost. What need is there to search? Only because of separation from my true nature, I fail to find him. In the confusion of the senses I lose even his tracks. Far from home, I see many crossroads, but which way is the right one I know not. Greed and fear, good and bad, entangle me.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: The bull never has been lost. What need is there to search? Only because of separation from my true nature, I fail to find him. In the confusion of the senses I lose even his tracks. Far from home, I see many crossroads, but which way is the right one I know not. Greed and fear, good and bad, entangle me.

Philip Kapleau Comments: The Ox has never really gone astray, so why search for it? Having turned his back on his True-nature, the man cannot see it. Because of his defilements he has lost sight of the Ox. Suddenly he finds himself confronted by a maze of crisscrossing roads. Greed for worldly gain and dread of loss spring up like searing flames, ideas of right and wrong dart out like daggers.

DT Suzuki Comments: She has never gone astray, so what is the use of searching her? We are not on intimate terms with her, because we have contrived against our inmost nature. She is lost, for we have ourselves been led out of the way through the deluding senses. The home is growing farther away, and byways and crossways are ever confusing. Desire for gain and fear of loss burn like fire, ideas of right and wrong shoot up like a phalanx.

Two: Discovering the Footprints

Along the riverbank under the trees, I discover footprints!

Even under the fragrant grass I see his prints.

Deep in remote mountains they are found.

These traces no more can be hidden than one’s nose, looking heavenward.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: Understanding the teaching, I see the footprints of the bull. Then I learn that, just as many utensils are made from one metal, so too are myriad entities made of the fabric of self. Unless I discriminate, how will I perceive the true from the untrue? Not yet having entered the gate, nevertheless I have discerned the path.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: Understanding the teaching, I see the footprints of the bull. Then I learn that, just as many utensils are made from one metal, so too are myriad entities made of the fabric of self. Unless I discriminate, how will I perceive the true from the untrue? Not yet having entered the gate, nevertheless I have discerned the path.

Philip Kapleau Comments: Through the sutras and teachings he discerns the tracks of the Ox. [He has been informed that just as] different-shaped [golden] vessels are all basically of the same gold, so each and every thing is a manifestation of the Self. But he is unable to distinguish good from evil, truth and falsity. He has not actually entered the gate, but he sees in a tentative way the tracks of the Ox.

DT Suzuki Comments: By the aid of the Sutras and by inquiring into the doctrines he has come to understand something; he has found the traces. He now knows that things, however multitudinous, are of one substance, and that the objective world is a reflection of the self. Yet he is unable to distinguish what is good from what is not; his mind is still confused as to truth and falsehood. As he had not yet entered the gate, he is provisionally said to have noticed the traces.

Three: Perceiving the Bull

I hear the song of the nightingale.

The sun is warm, the wind is mild, willows are green along the shore,

Here no bull can hide!

What artist can draw that massive head, those majestic horns?

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: When one hears the voice, one can sense its source. As soon as the six senses merge, the gate is entered. Wherever one enters one sees the head of the bull! This unity is like salt in water, like color in dyestuff. The slightest thing is

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: When one hears the voice, one can sense its source. As soon as the six senses merge, the gate is entered. Wherever one enters one sees the head of the bull! This unity is like salt in water, like color in dyestuff. The slightest thing is

Philip Kapleau Comments: If he will but listen intently to everyday sounds, he will come to realization and at that instant see the very Source. These six senses are no different from this true Source. In every activity the Source is manifestly present. It is analogous to the salt in water or the binder in paint. When the inner vision is properly focused, once comes to realize that that which is seen is identical with the true Source.

DT Suzuki Comments: He finds the way through the sound; he sees into the origin of things, and all his senses are in harmonious order. In all his activities it is manifestly present. It is like the salt in water and the glue in colour. [It is there, though not separably distinguishable.] When the eye is properly directed, he will find that it is no other thing than himself.

Four: Catching the Bull

I seize him with a terrific struggle.

His great will and power are inexhaustible.

He charges to the high plateau far above the cloud-mists,

Or in an impenetrable ravine he stands.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: He dwelt in the forest a long time, but I caught him today! Infatuation for scenery interferes with his direction. Longing for sweeter grass, he wanders away. His mind still is stubborn and unbridled. If I wish him to submit, I must raise my whip.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: He dwelt in the forest a long time, but I caught him today! Infatuation for scenery interferes with his direction. Longing for sweeter grass, he wanders away. His mind still is stubborn and unbridled. If I wish him to submit, I must raise my whip.

Philip Kapleau Comments: Today he encountered the Ox, which had long been cavorting in the wild fields, and actually grasped it. For so long a time has it reveled in these surroundings that breaking it of its old habits is not easy. It continues to yearn for sweet-scented grasses, it is still stubborn and unbridled. If he would tame it completely, the man must use his whip.

DT Suzuki Comments: After getting lost long in the wilderness, he has found the cow and laid hand on her. But owing to the overwhelming pressure of the objective world, the cow is found hard to keep under control. She constantly longs for sweet grasses. The wild nature is still unruly, and altogether refuses to be broken in. If he wishes to have her completely in subjection, he ought to use the whip freely.

Five: Taming the Bull

The whip and rope are necessary,

Else he might stray off down some dusty road.

Being well trained, he becomes naturally gentle.

Then, unfettered, he obeys his master.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: When one thought arises, another thought follows. When the first thought springs from enlightenment, all subsequent thoughts are true. Through delusion, one makes everything untrue. Delusion is not caused by objectivity; it is the result of subjectivity. Hold the nose-ring tight and do not allow even a doubt.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: When one thought arises, another thought follows. When the first thought springs from enlightenment, all subsequent thoughts are true. Through delusion, one makes everything untrue. Delusion is not caused by objectivity; it is the result of subjectivity. Hold the nose-ring tight and do not allow even a doubt.

Philip Kapleau Comments: With the rising of one thought another and another are born. Enlightenment brings the realization that such thoughts are not unreal since even they arise from our True-nature. It is only because delusion still remains that they are imagined to be unreal. This state of delusion does not originate in the objective world but in our own minds.

DT Suzuki Comments: When a thought moves, another follows, and then another–there is thus awakened the endless train of thoughts. Through enlightenment all this turns into truth; but falsehood asserts itself when confusion prevails. Things oppress us not because of the objective world, but because of the self-deceiving mind. Do not get the nose-string loose; hold it tight, and allow yourself no indulgence.

Six: Riding the Bull Home

Mounting the bull, slowly I return homeward.

The voice of my flute intones through the evening.

Measuring with hand-beats the pulsating harmony, I direct the endless rhythm.

Whoever hears this melody will join me.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: This struggle is over; gain and loss are assimilated. I sing the song of the village woodsman, and play the tunes of the children. Astride the bull, I observe the clouds above. Onward I go, no matter who may wish to call me back.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: This struggle is over; gain and loss are assimilated. I sing the song of the village woodsman, and play the tunes of the children. Astride the bull, I observe the clouds above. Onward I go, no matter who may wish to call me back.

Philip Kapleau comments: The struggle is over, “gain” and “loss” no longer affect him. He hums the rustic tune of the woodsman and plays the simple songs of the village children. Astride the Ox’s back, he gazes serenely at the clouds above. His head does not turn [in the direction of temptations]. Try though one may to upset him, he remains undisturbed.

DT Suzuki Comments: The struggle is over; he is no more concerned with gain and loss. He hums the rustic tune of the woodman, he sings the simple song of the village-boy. Saddling himself on the cow’s back, his eyes are fixed on the things not of this earth, earthly. Even if he is called to, he will not turn his head; however enticed, he will no more be kept back.

Seven: The Bull Transcended

Astride the bull, I reach home.

I am serene. The bull too can rest.

The dawn has come. In blissful repose,

Within my thatched dwelling I have abandoned the whip and rope.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: All is one law, not two. We only make the bull a temporary subject. It is as the relation of rabbit and trap, of fish and net. It is as gold and dross, or the moon emerging from a cloud. One path of clear light travels on throughout endless time.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: All is one law, not two. We only make the bull a temporary subject. It is as the relation of rabbit and trap, of fish and net. It is as gold and dross, or the moon emerging from a cloud. One path of clear light travels on throughout endless time.

Philip Kapleau Comments: In the Dharma there is no two-ness. The Ox is his Primal-nature: this he has now recognized. A trap is no longer needed when a rabbit has been caught; a net becomes useless when a fish has been snared. Like gold which has been separated from dross, like the moon which has broken through the clouds, one ray of luminous Light shines eternally.

DT Suzuki Comments: Things are one and the cow is symbolic. When you know that what you need is not the snare or set-net but the hare or fish, it is like gold separated from dross, it is like the moon rising out of the clouds. The one ray of light serene and penetrating shines even before days of creation.

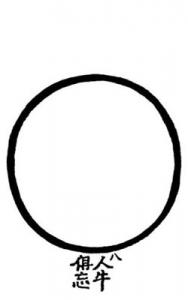

Eight: Both Bull and Self Transcended

Whip, rope, person, and bull — all merge in No-Thing.

This heaven is so vast no message can stain it.

How may a snowflake exist in a raging fire?

Here are the footprints of the patriarchs.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: Mediocrity is gone. Mind is clear of limitation. I seek no state of enlightenment. Neither do I remain where no enlightenment exists. Since I linger in neither condition, eyes cannot see me. If hundreds of birds strew my path with flowers, such praise would be meaningless.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: Mediocrity is gone. Mind is clear of limitation. I seek no state of enlightenment. Neither do I remain where no enlightenment exists. Since I linger in neither condition, eyes cannot see me. If hundreds of birds strew my path with flowers, such praise would be meaningless.

Philip Kapleau Comments: All delusive feelings have perished and ideas of holiness too have vanished. He lingers not in [the state of “I am a] Buddha,” and he passes quickly on through [the stage of “And now I have purged myself of the proud feeling ‘I am] not Buddha.'” Even the thousand eyes [of five hundred Buddhas and Dharma masters] can discern in him no specific quality. If hundreds of birds were now to strew flowers about his room, he could not but feel ashamed of himself.

DT Suzuki Comments: All confusion is set aside, and serenity alone prevails; even the idea of holiness does not obtain. He does not linger about where the Buddha is, and where there is no Buddha he speedily passes on. When there exists no form of dualism, even the thousand-eyed one fails to detect a loophole. A holiness before which birds offer flowers is but a farce.

Nine: Reaching the Source

Too many steps have been taken returning to the root and the source.

Better to have been blind and deaf from the beginning!

Dwelling in one’s true abode, unconcerned with that without —

The river flows tranquilly on and the flowers are red.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: From the beginning, truth is clear. Poised in silence, I observe the forms of integration and disintegration. One who is not attached to “form” need not be “reformed.” The water is emerald, the mountain is indigo, and I see that which is creating and that which is destroying.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: From the beginning, truth is clear. Poised in silence, I observe the forms of integration and disintegration. One who is not attached to “form” need not be “reformed.” The water is emerald, the mountain is indigo, and I see that which is creating and that which is destroying.

Philip Kapleau Comments: From the very beginning there has not been so much as a speck of dust [to mar the intrinsic Purity]. He observes the waxing and waning of life in the world while abiding unassertively in a state of unshakable serenity. This [waxing and waning] is no phantom or illusion [but a manifestation of the Source]. Why then is there need to strive for anything? The waters are blue, the mountains are green. Alone with himself, he observes things endlessly changing.

DT Suzuki Comments: From the very beginning, pure and immaculate, he has never been affected by defilement. He calmly watches growth and decay of things with form, while himself abiding in the immovable serenity of non-assertion. When he does not identify himself with magic-like transformations, what has he to do with artificialities of self-discipline? The water flows blue, the mountain towers green. Sitting alone, he observes things undergoing changes.

Ten: In the World

Barefooted and naked of breast, I mingle with the people of the world.

My clothes are ragged and dust-laden, and I am ever blissful.

I use no magic to extend my life;

Now, before me, the dead trees become alive.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: Inside my gate, a thousand sages do not know me. The beauty of my garden is invisible. Why should one search for the footprints of the patriarchs? I go to the market place with my wine bottle and return home with my staff. I visit the wineshop and the market, and everyone I look upon becomes enlightened.

Nyogen Senzaki Comments: Inside my gate, a thousand sages do not know me. The beauty of my garden is invisible. Why should one search for the footprints of the patriarchs? I go to the market place with my wine bottle and return home with my staff. I visit the wineshop and the market, and everyone I look upon becomes enlightened.

Philip Kapleau Comments: The gate of his cottage is closed and even the wisest cannot find him. His mental panorama has finally disappeared. He goes his own way, making no attempt to follow the steps of earlier sages. Carrying a gourd, he strolls into the market; leaning on his staff, he returns home. He leads innkeepers and fishmongers in the Way of the Buddha.

DT Suzuki Comments: His humble cottage door is closed, and the wisest knows him not. No glimpses of his inner life are to be caught; for he goes on his own way without following the steps of the ancient sages. Carrying a gourd he goes out into the market; leaning against a stick he comes home. He is found in company with wine-bibbers and butchers; he and they are all converted into Buddhas.