DOUBT & FAITH

A Zen Meditation

“The opposite of faith is not doubt; it is certainty. It is madness. You can tell you have created God in your image when it turns out that he or she hates all the same people you do.”

Anne Lamont

With Buddhism like with all religions doubt is considered a problem.

And there are aspects to doubt which can make it count as one of the great hindrances along a spiritual path. There is a superficial skepticism which flirts with nihilism that is doubt. There is a hesitance, an inability to get in gear, to get on with it that is doubt. There is a lack of trust, an inability to think someone else might actually know something important, might actually be able to guide which is doubt. Each of these are noted and are labeled. Hindrance.

The story of Thomas the Doubter only occurs in the Gospel of John. John was written about a hundred years after Jesus’ death and is considered a “theological” document rather than an attempt at capturing the life of that remarkable spiritual teacher. So, in the story when Thomas asserts how he needs to actually touch the wounds before he will believe, he’s set up to be the superficial kind of doubter.

In fact, the point of the story as it is presented is how much better it is to believe without evidence.

I think not.

And one of the wonderful things about the Zen tradition is how it engages doubt.

And, in the Christian story, just by making up the story an archetype appears, a kind of spiritual investigator, someone who must know for themselves. And all of a sudden, we have a figure who makes sense. Bringing their whole being to the project, not putting their brain down as they enter that particular church. Sort of like doubt in Zen.

And Zen certainly runs with that approach to the spiritual. It suggests there is way where doubt is the key. The question is navigating away from the doubts that are unhealthy or at least unproductive and toward doubt as the great engine of our spiritual lives.

This particularly focuses on how we engage koans. And it’s sorted out from run of the mill doubt, the half-hearted thing that prevents our throwing ourselves into some project. It becomes Great Doubt, complete with the capitals. But it has larger applications for our spiritual lives. We’ve set an intention, we’ve made commitments, we have begun a practice, we work with a spiritual director. Perhaps we have a koan. Perhaps our practice is a form of silent presence.

Then what?

Among my memories of my youth studying with the late British born Soto Zen priest Houn Jiyu Kennett, was early on asking her a question. I’d been practicing for a couple of years at a branch of the San Francisco Zen Center. But this was my turning point from something I felt pretty serious about to what would become the bright thread running through the whole of my life.

The question was “How much faith do I have to have to do this?” It was a real question. To be honest, I didn’t have a lot of faith. As I’ve said. I’d left my childhood fundamentalist Christianity and while I’d flirted with Vedanta, I had a lot of trouble with any assertions about reality that moved too much from the observable, the measurable, the quantifiable.

She was a large woman with a quick smile and eyes that I felt cut right into the center of my being. She smiled. She looked. And she replied, “All that you need to believe is that maybe, possibly, you can learn something.” And that was my mustard seed, that tiniest of things. As it turns out, she was right.

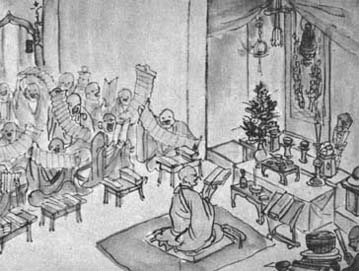

As I began to dig into the Zen way, I learned of the three maxims of our path was framed by the Eighteenth-century Rinzai master Hakuin Ekaku. The work of Zen calls us to great doubt, great faith, and great energy.

Truthfully, I am most strongly inclined to the doubt aspect of this path. The “way of not knowing” is what so obviously differentiates Zen out from almost all other spiritual schools, including most Buddhist schools. I’ve explored deeply, reflected at length, talked, and written on this not knowing a fair amount. Great energy is also so important for a way that famously holds up “self-power,” our own grit, our individual determination and effort as a generative element. I really found it important that what I actually do, or do not do is considered important. And, I really liked when I found a commentator suggest that the word for “energy” could also be translated as “wrath.” I realized there is much to dig into with it.

But, here, I want to hold up faith. Faith is something much less engaged in Zen, at least when we talk about it. When we do speak of it, we usually circle around how little faith we need, like with my memory of my old ordination master, Kennett Roshi. However, it really is important, and calls for our attention.

And with that I’m taken with how the Zen teacher Albert Low once observed he “always balked at the ‘great faith’ part because I could not help confuse faith and belief.” And that was my problem, as well. Let’s unpack.

Now in fact the words faith and belief are synonyms. Faith enters English from the Latin via French, while belief comes out of the Germanic language family. Both carry connotations of trust, and each have other overlays that give them complexity and nuance. The distinction Sensei Low makes is also one we hear from many Christians, and which I first heard in seminary. And I like it. It has emerged because there are legitimate distinctions to be found when we talk about what it is we have faith in, what it is we believe. And in English, as it happens, we have these two words we can work with.

I want to suggest as a working definition that belief be used for those things that are asserted as true by someone in authority, we read it, we were told it, and which we simply accept. And the emphasis is on that acceptance on the face of it. Spiritually this is the “It’s in the book, I believe it, that settles it” stance on a refrigerator magnet I saw in a Christian bookstore.

Often belief in this sense is presented with a modifier like “mere,” showing this is the lesser term of the two. Although, if we’re honest with ourselves, we can see we believe in all sorts of things in this exact sense. As a practical matter you can’t examine everything. We have to have some confidence in some sources of authority, or we can’t function. For example, we believe the sun will rise whether we have investigated the matter in any legitimate sense of that word investigate, or not.

Faith is related to that definition of belief, but it has been parsed out, allowing a more dynamic quality. While we still are talking about trust, we are also talking about engagement and reflection. It is the dynamic of our lives where we accept some guidance, maybe that little bit of “belief that I can learn something.” Then do it. Then reflect on that doing. And maybe finding nope, it wasn’t true. At least for me. Or, yes, there’s something here. At least for me. And, then going at it again from this deeper, or perhaps we can even say, more mature perspective. The process of faith is ongoing.

The Buddhist word that is usually translated as faith is saddha in Pali, and similarly pronounced in Sanskrit. It is understood pretty fully in that second sense of faith, that the assumption is the teachings are only provisionally accepted. Then we are asked to investigate for ourselves, to taste and know whether, as the Zen line goes, “that sip of water is cool or warm.”

Here’s where the lovely observation by Anne Lamont gets really helpful. “The opposite of faith is not doubt; it is certainty.” Certainty is the killer. Faith as not the opposite of doubt becomes the companion of doubt, and together doubt and faith open us to new visitas.

Then, as the Flower Ornament Sutra sings to us:

Faith is the basis of the Path, the mother of virtues,

Nourishing and growing all good ways,

Cutting away the net of doubt, freeing from the torrent of passion,

Revealing the unsurpassed road of ultimate peace.

And it continues:

Faith is generous …

Faith can joyfully enter the Buddha’s teaching;

Faith can increase knowledge and virtue;

Faith can ensure arrival at enlightenment …

Faith can go beyond the pathways of demons,

And reveal the unsurpassed road of liberation.

Here we find that little mustard seed planted and growing. And, I hope, reading these words we find ourselves invited into that dynamic, where a small belief, through active engagement, opens our hearts to ever deeper contours of wisdom, compassion, liberation.

And, there’s another way, yet, into this path of faith.

Let’s talk just briefly about Pure Land Buddhism. Zen is a path of energy and effort, maybe even wrath. The Pure Land goes in an entirely different direction. Or at least it appears to. Its founders suggest we live in the last age, a time of disintegration, where human access to wisdom is lost, and there is in fact no help for us in our own actions. We are all of us too broken, too defiled by our grasping, our aversions, and our endlessly complex certainties. We can’t cut the thread of confusion. Not by our own hand. Me, I’ve felt this. I believe it’s hard to look at the world and our own hearts and not find resonances with this perspective, not if we’re being honest with ourselves.

And, in response to this they tell a story of a Buddha, Amitabha or Infinite Light in Sanskrit, called Amida in Japanese, who presides over a Pure Land, think Heaven. And, he has promised if we just call on him, he will carry us to that Pure Land where the way is open and clear and free. It’s called Amitabha’s Primal or Original Vow. It is the great vow of the heart. I believe if we’ve walked the great way for any length of time, we’ve had intimations of what this story points to.

It is a good news. We don’t have to have a strong practice, we don’t even have to be good people. These are upayas, skillful means, but they’re tools. Whoever we are, what ever our situation in life, we call on Amitabha and we will be saved. Period. We give our heart, our trust, and we will be saved. Sound kind of familiar? Now, one can ask is this just one more tool?

The turning moment for me in this reflection is called shinjin, which according to the great teacher Shinran Shonin means the “mind of reality.” After he had spent twenty years with the disciplines of the Tendai monastery, he turned to that invocation, calling on Amida, Amitabha, Infinite Light. After a year there was a moment, a turning of the heart and mind. He awakened to shinjin.

This is the really important part. Most Pure Land teachings suggest you believe and call on Amitabha, then when you die you will be reborn into that Pure Land. It is another cultivation of a small seed. With Shinran, as I understand him, you surrender into Amitabha’s original vow, into the heart of love for all beings, into the mother of the world, and at that instant you are born into the Pure Land. There is a mustard seed, that smallest of things. It’s always with us. And, and the great mustard bush is already there, as well. Already here. And the birds of heaven, all of them, all of us have already long found their roost.

That sounds a lot like Zen’s awakening to me. A bit flowery in the presentation. But, so are many of the traditional Zen stories. And, oh my, the great invitation. The original vow. It’s all here.

So, in sum: I follow a way of doubt. I follow a way of energy, sometimes even a way of wrath. But, in the last analysis I’ve found this way is one of putting down my opinions and opening up my heart. After all the struggling, finally, finally, this way is actually one of opening my hand and my eyes and seeing the grace of this world.

Zen is a path of great faith. Faith in what is. As we open up we find self-power burns away. As we put it down other power burns away. And, the world changes. Christian is gone. Buddhist is gone. Atheist, Hindu, Muslim. Each are gone, and in their place each a burning beacon showing forth.

And what is found in that light?

Well. Just this. Just this. Right here. The Pure Land. Right here. Heaven. Right here the realm of bodhisattvas and saints, that great bush, the home of the birds of heaven.

And, of course, of course, all the hell realms, as well.

Each seeking integration within the great mystery.