MAY YOU LIVE IN INTERESTING TIMES

A Meditation on Olympia Brown & Navigating Hard Times

James Ishmael Ford

A Sermon delivered at the

First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles

9 January 2022

I come to you today with some bad news.

But, not to worry unduly. I also have good news to share. And they’re connected.

Let me start with the bad.

Okay. For most of us it isn’t exactly news. These are, you may have noticed, complex and troubled times. In fact, a picture perfect example of what is sometimes characterized as that ancient Chinese curse. For those who care about such things, the phrase isn’t in fact from ancient China. Although no doubt the reality of it is recognizable there. The curse goes, “May you live in interesting times.”

These are interesting times, for sure. We’ve just passed that ugly anniversary of Mr Trump’s attempted putsch. And looking at the statistics about people’s views on the subject, we appear to still be in a rolling power grab. American Democracy is tottering at some edge, and where it will land is by no means clear.

Some parts of these interesting times are always with us, it would seem. A very small number of people control more wealth than has been imagined in any empire of the past. A larger number of people are living astonishingly comfortable lives, but precariously, in danger at near any moment of tumbling into the ever-growing mass of people desperately seeking just to survive.

There are great advances in equality in some areas. At the same time fierce scapegoating of the powerless, the poor, immigrants, and minorities of various sorts, all for the ills overtaking us becomes an amazing act of misdirection. Largely and sadly willful, as we are every one of us to some degree complicit in this bit of kabuki.

And of course, of course, there is our hurting planet. Our global climate is shifting in ways we can only put educated guesses to. But those educated guesses tend to be dire. Personally, I am anxiously following the fate of the Antarctic ice shelf, which if it collapses has the chance of pretty much instantly raising the world’s sea level by a couple of feet.

Interesting times, indeed. As we have such an uneven track record of meeting catastrophes, I’m more than nervous on our behalf. Hard to see how much of this turns out well.

And that brings us here. To this place. And to this community.

And to that good news.

Here we proclaim a message of hope. Without exception we and all of life on this little planet are joined. Our lives without exception are intertwined. And what happens to one of us, happens to all. Without exception.

In very real ways this is a fact on the ground. And there’s something more in it. This is a spiritual vision. It is something we can know as more than a very important fact on the ground. It can be a vision that we know from the cells of our bodies, as something that informs our dreams and our actions. We find it by stopping and noticing. Noticing and letting go. There’s a place for action, but first, we need to let go, especially of our opinions. First, to see raw and intimate. We do this by paying attention and letting go.

I’ve found the Zen tradition has the practices down best. Not perfect. Nothing made by human hands is going to be perfect. And all things “made” are made by human hands. But there is a seed of this practice found pretty much everywhere. Pay attention and let go. Both Universalists and Unitarians have it. As do, as I said, other traditions.

It is the ancient heart of all spiritual practices. And it’s something amazing, when we do it. It is a gate to perspective, and even to something that can be called a peace that passes all understanding. And, also, this vision of our radical interdependence has practical consequences. There is work for us out of this great insight.

Today I want to spend the balance of our time examining what those practical consequences are by telling a story. A real story. A true story. Today I want to share the life of one person who met the possibility of despair and overcame it in ways that seemed impossible at the time she did it. And in describing her life, I suggest we might be hinting at ours, and because of her and our connections to her, recall what our lives might be.

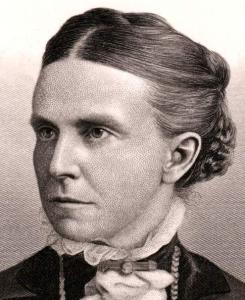

Today I share here the life of our mother Olympia Brown. If we pay attention, she can show us the way. Not the only way. But a true way.

Lephia and Asa Brown were farmers living in Prairie Ronde, Michigan. Their first child, Olympia was born on the 5th of January, in 1835. So, you might note she was born 187 years ago, plus four days.

Olympia was the eldest of their four children. The family was deeply religious. And it seems they valued education as dearly as their Universalist faith. I suspect these things were in some ways connected. Seeing the need in that frontier town, her parents provided the land for a school, Asa then built the schoolhouse with his own hands. And after that went the rounds of his neighbors to solicit support for a teacher.

Young Olympia often rode with her father as he made these rounds. At home her mother gave the children’s education, for both the boys and girls, her highest priority. As a small aside for those with a genealogical interest, according to Laurie Carter Noble who provided much of the background material I use here, Lephia and Asa would in the fullness of time become Calvin Coolidge’s great great aunt & uncle. We really are all connected. Often, whether we like it or not.

When it came time to attend college Olympia was refused admission to the University of Michigan because of her gender. So, she registered at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary in Massachusetts. She was quickly dissatisfied with what proved to be a program more designed to produce a proper young lady than an educated person. After one year at Mount Holyoke Olympia transferred to Antioch College, where the radical Unitarian educator Horace Mann was the school’s president. There were still gender inequities, but she was given access to a real education. At least so long as she was willing to push to the front. She was. And she was so successful her family ended up moving to Yellow Springs to support her siblings who all ended up attending Antioch.

Among young Olympia’s heroes was Antoinette Brown, later Blackwell. She’s so important for Olympia’s story, we need to make a small digression here. Antoinette was not a relative, you may not know this, but Brown is a fairly common name. Antoinette was a Congregationalist, who attended Oberlin and after completing her undergraduate degree continued on with theological studies. Antoinette completed the coursework, but was denied a degree despite her quickly emerging reputation as a theologian, simply because of her gender.

Leaving the school Antoinette went to work for Frederick Douglas, writing for his paper, the North Star. She also was invited to speak at the first National Women’s Rights Convention in 1850. Finally, Antoinette was ordained by her congregation, a bottom line right within our congregational polity. She then served a couple of Congregational churches, although like with her being denied her theological degree, she was not recognized as a minister by the national denomination.

Antoinette became one of the leading intellectual and spiritual figures in the years prior to the Civil War, speaking out on religion, abolition and women’s rights. I want to add with a digression within this digression that in 1878 she crossed over to the Unitarians and her ministry was finally officially acknowledged by a denomination – ours. But, while I find it really, really interesting, that’s getting ahead of the story, which is Olympia’s story.

While an undergraduate at Antioch young Olympia managed to arrange for Antoinette to come and speak. As the chief organizer for the event Olympia got to spend some time with the formidable Antoinette. Formidable meeting formidable. Such encounters can go in several directions. For them, they immediately bonded.

Inspired, Olympia decided that ministry was also her calling, her destiny. As she came close to graduating from Antioch, Olympia began applying to theological schools. Oberlin offered the same arrangement they gave to Antoinette. She could attend school but would not be given a diploma. Our Unitarian seminary at Meadville responded that, “the trustees thought it would be too great an experiment.” And refused her admission.

But the Universalist seminary at St Lawrence University accepted her, if reluctantly. Dr Ebenezer Fisher, the president wrote her saying “It is perhaps proper that I should say, you may have some prejudices to encounter in the institution from students and also in the community here… (However, t)he faculty will receive and treat you precisely as they would any other student.” In this rather long letter he admitted he personally “did not think women were called to the ministry.” But then concluded, “…I leave that between you and (God).” Olympia thought that was where the decision should be made, ignored the warnings, and in 1861, as the American Civil War was beginning, she entered divinity school. Three years later she graduated, was awarded her degree, and, most importantly, was ordained to the Universalist ministry. In 1864 Olympia Brown became the first woman regularly ordained in a national denomination.

In the same year, as the Civil War was winding down, Olympia was called to her first parish in Weymouth Landing, Massachusetts. While serving there, once abolition had been won, for which she was a tireless worker, she threw herself fully into the struggle for women’s suffrage. She worked closely with Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone and others. She also began to speak around the country.

In 1870 Olympia accepted a call to the pulpit of the Universalist Church in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Three years later she married John Henry Willis, shocking the sensibilities of the day by retaining her family name. This appears to have been a perfect love match. John actively supported her dual callings as a parish minister and increasingly as a social justice activist. They had two children, Henry & Gwendolyn.

During her first pregnancy a faction in the Bridgeport church found her swelling midsection unseemly and moved to have a vote of dismissal. While it failed, Olympia felt her ministry compromised and resigned after her son’s birth. From there she entered into a conversation with the leadership of the Unitarian church in Racine, Wisconsin, where she was warned “a series of pastors easy-going, unpractical and some even spiritually unworthy… had left the church adrift, in debt, hopeless and doubtful whether any pastor could again rouse them.”

Olympia would later write, “Those who may read this will think it strange that I could only find a field in run-down or comatose churches, but they must remember that the pulpits of all the prosperous churches were already occupied by men, and were looked forward to as the goal of all the young men coming into the ministry with whom I, at first the only woman preacher in the denomination, had to compete. All I could do was to take some place that had been abandoned by others and make something of it, and this I was only too glad to do.”

With her call, John closed his business, and traveled ahead to Racine, where he purchased a part ownership of the local newspaper, the Racine Times Call. Olympia settled into her new ministry, bringing healing and competence to the work. She also began to make the Racine church a center for progressive social thought, bringing in as speakers her old friends and colleagues Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Julia Ward Howe. The church flourished.

After nine years serving the congregation, and not long after her father’s death, Olympia decided to leave the parish and full-time ministry in order to devote all her energies to the suffrage movement. She was fifty-three. Olympia became the leader of the Wisconsin Suffrage Association and served as vice-president of the National Woman Suffrage Association.

John died, unexpectedly, in 1893. Olympia wrote of this, how “Endless sorrow has fallen upon my heart. He was one of the truest and best men that ever lived, firm in his religious convictions, loyal to every right principle, strictly honest and upright in his life… with an absolute sincerity of character such as I have never seen in any other person.” Often, I’ve found, those who succeed greatly, succeed in significant part because there is someone with them, giving them fierce support. For much of her life thanks to John, Olympia had that support.

She burned for the right to vote, and gradually moved toward more confrontational engagements. As such in 1913 she became a central leader of the Woman’s Party. When President Wilson failed in his promises to support suffrage, Olympia led a protest where she burned his speeches in front of the White House. I tried to find an archive photograph from that event. I couldn’t, but I can imagine it. The time was right. The smell of justice was in the air. And no doubt it smelled much better than the damp ashes Olympia left in front of the White House.

Indeed, finally, finally the tide had turned. Women won the right to vote nationally in 1919. Olympia and her old mentor Antoinette Brown Blackwell were among the few original leaders of the movement who had lived long enough to cast their own votes. In 1920 at the age of 85, Olympia cast her first presidential vote. To my mind somewhat surprising, for Warren Harding. In 1924, her second and last vote for president she supported the radical Robert La Follette, who somehow seemed more appropriate to me than Mr Harding for winning her vote. But that’s how it works with self-determination. We make our choices. And we live with the consequences. Sometimes we even learn lessons.

In those years following winning universal suffrage at least on paper, people of color were still waiting for their full access to the ballot. And Olympia returned to that battle as she had when advocating abolition. Finally, as age overtook her, she retired, spending her summers in Racine and wintering with her daughter who taught Latin and Greek at the Bryn Mawr Prep School in Baltimore. In 1926, at the age of ninety-one, she died in Baltimore. According to the obituary in the Baltimore Sun, “Perhaps no phase of her life better exemplified her vitality and intellectual independence than the mental discomfort she succeeded in arousing, between her eightieth and ninetieth birthdays, among… conservatively minded Baltimorans.”

She was buried in Racine next to her husband, John.

So, briefly, what’s the takeaway? For us, here, today? For you and me? Remembering the interesting times. Knowing the dangers we face. All of them. Well, it’s not that hard. We can follow Olympia’s example. At the front, as a Universalist, she saw the connections. This is a most important thing.

And this is the thing we need most to notice. Olympia saw into the connections and found the mysteries of universal love. Of love beyond belief. Of love as the glue of the worlds, and the ever rising possibility of change. Good news indeed. And then she did the next thing. She acted upon those principles with respect for the dignity of all beings, including herself. Of course. And she brought tenacity to the project. Fierce tenacity.

That’s what Olympia Brown did. Our mother has shown us the way.

And that’s what we are called to do. Today. See the connections. And then act, as best we can.

Nothing more. And nothing, nothing less.

Amen.

My old colleague and mentor Dr Janet Bowering bringing Olympia Brown to life…

And. And…