THUNDER AND LIGHTNING

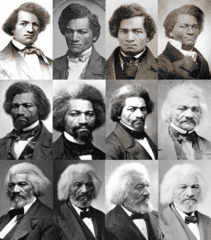

Frederick Douglass’ Liberation Theology

A sermon delivered at the

First Unitarian Church of Los Angeles

February 20th, 2022

“If there is no struggle, there is no progress. Those who profess to favor freedom, and yet depreciate agitation, are men who want crops without plowing up the ground. They want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters. This struggle may be a moral one; or it may be a physical one; or it may be both moral and physical; but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into slavery, probably in February of 1817. Maybe the year after that. In later years he would observe the 14th as his birthday because he had a fragmentary memory that his mother called him her little Valentine.

He was born on a plantation on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay, in Maryland. His mother Harriet named him Frederick and added in those hopeful hints of what he could become with an Augustus and a Washington. He never knew for sure, but his fellow slaves believed his father was Harriet’s owner, Aaron Anthony. As an infant Frederick was separated from his mother and raised by his maternal grandmother Betsy and her free husband on another plantation a few miles away. His mother would visit him at night. Frederick had memories of her cuddling him, but she was always gone before he awoke.

When he was six, he was separated from his grandparents and eventually sent to Baltimore. His mother died the next year. Frederick’s new owner’s wife Sophia Auld made sure he was treated humanely and taught him to read. Her husband disapproved of this, so she stopped shortly after he mastered the rudiments. But he persisted in studying on his own, although he then had to do it in secret.

At about thirteen Frederick experienced a spiritual awakening.

“I consulted a good old colored man named Charles Lawson, and in tones of holy affection he told me to pray, and to “cast all my care upon God.” This I sought to do; and though for weeks I was a poor, broken-hearted mourner, traveling through doubts and fears, I finally found my burden lightened, and my heart relieved. I loved all mankind, slaveholders not excepted, though I abhorred slavery more than ever. I saw the world in a new light, and my great concern was to have everybody converted. My desire to learn increased, and especially, did I want a thorough acquaintance with the contents of the Bible.”

I’ve thought about his awakening, and that critical experience that included even his oppressors. It would play out over the years in very interesting ways. Ways I believe helpful to us, today.

Frederick read what he could, mostly newspapers, pamphlets, and whatever books came his way. In later years he would cite the Columbian Orator, as especially important. He’d been told about it, and saved money from shining people’s shoes, until he had the fifty cents it cost to purchase the book. It was a late eighteenth century anthology of speeches attributed to Socrates and Cato as well as actual speeches by George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and others. He credited it both with opening his eyes to the thought of human rights, and how those rights should extend to him, as well as the potential power of oratory.

For a time, he was hired out to another plantation where the owner allowed the slaves to study the New Testament. Which he did diligently. By the time he was sixteen, fearing his growing knowledge and perhaps lack of proper deference Frederick was sent to a notorious “slave-breaker,” where he was constantly beaten and whipped.

At some point when he could bear it no more, Frederick stood up and physically confronted the man. I am unclear how, but instead of some horrific fate, the slaver backed off. This would be another awakening experience for him. For him, it would seem, in some ways, God would become the spirit that led him to stand up. God was becoming an urge to freedom.

In 1837 he met Anna Murray, a free black woman. She encouraged his desire to escape slavery and had the resources to help. There are several stories of how he did this, but basically, he was able to take the train to Philadelphia disguised as a sailor and carrying documents procured for him by Anna. From there he went up to New York City. It took less than a day to pass from slavery into freedom. I think about that, how close and how far, how easy, and how dangerous.

Years later he would write, “I prayed for freedom for twenty years, but received no answer until I prayed with my legs.” Mark this line. I’m going to return to it before we’re finished.

Once in New York, Frederick was joined by Anna. They married eleven days later, on September 15th, 1838. Their marriage would last 44 years, until Anna’s death. At first, they took the name Stanley, then Johnson, before settling on Douglass as their freedom name.

The couple investigated the predominately white churches in the city but saw that they were segregated, so he and Anna joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. Within a year he was licensed as a lay preacher, where he given the opportunity to hone his rhetorical skills. He also was active in abolitionist societies, and considered William Lloyd Garrison’s weekly Liberator, second only to the Bible in importance to him.

In 1845 he published his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. It was an instant best seller and changed his life, and, well, it would change America. With his newfound resources Douglass traveled to Ireland, Scotland, and England. English admirers purchased his freedom to ensure his safety when he returned to the United States.

While in the British Isles he experienced a level of acceptance he had never encountered before, but also was shocked at some of the extreme poverty he witnessed. He began to see that his call to liberation extended beyond black slaves. After returning to the United States, Douglass started his own newspaper, in Rochester, New York, the North Star. Its motto was “Right is of no Sex – Truth is of no Color – God is the Father of us all, and we are all brethren.”

In 1848 he attended the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, where he made an impassioned speech in support women’s suffrage. In Rochester Frederick and Anna were active in the Underground Railroad until the Civil War, where they hosted, housed, fed, and helped move to freedom more than four hundred escaped slaves.

In 1847 Douglass famously met John Brown at Brown’s home in Springfield, Massachusetts. At that time Brown had a plan for a mass escape of slaves using an armed militia to guard them on their way to freedom. Douglass had long been an advocate of a peaceful end to slavery. But, by this time he had begun to lose hope in a peaceful abolition. While that plan never materialized, they became friends.

And there also was a powerful tension between them. Brown was ready to wade hip deep through blood to end slavery, Douglass had more complicated feelings about the best way through. In 1859 Brown told Douglass of his plan to capture Harpers Ferry and trigger a slave revolt. He asked Douglass to join him. What happened from there is debated by scholars. Some say Douglass promised to recruit volunteers and show up for the attack. Others, and Douglass himself, said that he tried to dissuade Brown, saying the venture was suicidal. What we do know is that Douglass did not join him, and the assault failed, and John Brown was hung for his efforts. Douglass would later write that whether from “discretion or my cowardice,” I did not join Brown. This decision would haunt him for the rest of his life.

However, his name was attached to the event, and Douglass found it wise to go to England for a while. When he returned the Civil War was all but certain, and he threw his efforts into supporting the cause. When the war came, he passionately supported the effort. He and Anne had five children, one died as a child. Of their three sons, all served in the Army, the oldest, Lewis, rising to Sergeant Major, the highest rank open to black servicemen.

Douglass’ relationship with Abraham Lincoln was fraught. In the 1864 reelection campaign, he actually supported John Fremont, a fascinating and quixotic personality worth knowing more about. In a famous speech Douglass delivered in 1876, he gave as good an assessment of Lincoln as I’ve read. “Though Mr. Lincoln shared the prejudices of his white fellow-countrymen against the Negro, it is hardly necessary to say that in his heart of hearts he loathed and hated slavery….” And in the push come to shove, while painfully slow, much too slow, “Can any colored man, or any white man friendly to the freedom of all men, ever forget the night which followed the first day of January 1863, when the world was to see if Abraham Lincoln would prove to be as good as his word?” That was the day when Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, the actual legal beginning to the end of slavery in the United States.

After the war Douglass continued to work for civil rights for African Americans and for women. He served for a time as president of the Freedman’s bank. In 1872 he was nominated as Victoria Woodhull’s vice-presidential running mate for the Equal Rights Party.

Anna died in 1882. Douglass dropped into a deep depression for a year. When he recovered, he found a second love with Helen Pitts, a white suffragist and abolitionist co-worker. His family, well, pretty much everyone disapproved. But they married and remained so for eleven years, until Frederick Douglass’ death. He had a fatal heart attack in the evening after delivering an address at the National Council of Women, in Washington.

It was February 20th, 1895. 127 years ago, today.

Frederick Douglass was believed to be 77 or maybe 78.

For me among the most important things about Frederick Douglass was his spirituality.

Douglass’ narrative as he presented it in the three versions of his autobiography, is essential the story of the conversion of souls. I should add this is not universally accepted. His condemnation of slave holding Christianity is relentless. So much so some say while he tipped his hat to some hypothetical authentic Christianity, the truth was he walked away from the religion. I think that misses the genuine, powerful, and for us potentially liberating spirituality that he actually espoused.

Theologian James Cone observes how “the theme of liberation expressed in story form is the essence of black religion. Both the content and the form (of these narratives, including Frederick Douglass’) were essentially determined by black people’s social existence… They did not debate religion on an abstract theological level but lived their religion concretely in history.”

Now Douglass was theologically literate. He read widely. And was particularly influenced in his mature spiritual reflections by David Friedrich Strauss, who sought to understand the historical Jesus, and most of all by Ludwig Feuerbach, who brought a naturalistic and rational critique to Christianity. And incidentally is considered a signal influence on Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud, and Karl Marx, as well as Frederick Douglass.

And. There is no doubt Douglass’ theological stance was pragmatic. I think that line about his escape from slavery, “I prayed for freedom for twenty years, but received no answer until I prayed with my legs.” And he took that impulse and refined it over the years informed by some of the best thinking of his era.

James Cone, one of the important spiritual thinkers in my life, observes how the will to freedom precedes the shape of religion, but for Black religion, the Bible and Christianity provided the symbols and “conceptual language” to engage and understand what was going on. And, critically, how to proceed. The urge for freedom preexists, but it is expressed as a spirituality, and with spiritual language. I think this is very important.

And equally important, I find, is that for Douglass and the religion of the enslaved, it wasn’t about finding a vehicle to express their urge to freedom. There was no space between that urge and the story of Exodus as something lived, there was no space between Jesus wandering the Galilee proclaiming a freedom that was partially in the future and absolutely in this moment, and Douglass’ feelings of what is and and what might be. This is something visceral, both ancient and as new as our most recent breath.

Freedom is about religion, or, it becomes something else. Freedom, that word, has many faces. Some, frankly, are false. But, others open us into the mysteries of our lives and deaths. And with that I think about the symbols of the Western religious tradition, both the stories of Jesus and his dealings with the poor as well as his call into a realm that partially exists in some future place, and at the very same time is found right here and right now.

Me, I was raised a poor people’s Baptist. In the religion I was taught it was more likely that a camel would pass through the eye of a needle than a rich man would get into heaven. And there was no fooling around hypothesizing that maybe there was a gate into Jerusalem that required camels to get on their knees. Or that the word we translate as camel really meant rope and so while extremely hard, it wasn’t impossible. Both are hogwash. The passage is unambiguous.

There is a thread in Christianity that favors the poor and oppressed. Jesus was born among the poor. He was poor his whole life. He was a carpenter, and some take that to make that to mean he was their version of middle class, or maybe better. But except for some merchants, landowners, and collaborators with the Romans, everyone else was poor. Jesus belonged to that group. And if you’re poor, you know that the world is not fair. And with that comes a sense of what is fair. And, from there. Well, Jesus said he came to cast fire on this earth…

In his classic Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire tells us those “who oppress, exploit, and rape by virtue of their power, cannot find in this power the strength to liberate either the oppressed or themselves. Only power that springs from the weakness of the oppressed will be sufficiently strong to free both.” This is some strange and mysterious truth.

It is here we find Frederick Douglass, who famously named his God, the “God of the oppressed.” Douglass called out the false Christianity professed by people who held slaves and those who remained in communion with them. He proclaimed a religion of resistance, a different kind of Christianity, more clearly informed by the Exodus story.

In the Gospel according to Matthew Jesus is said to have said, “Truly, I say unto you, inasmuch as you have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, you have done it unto me.” I’ve seen people interpret this to mean don’t mess with Christians. While everyone else is fair game. And that’s not what it says. The brethren are the poor, the oppressed, the left behind. To miss this is to miss the possible that is contained within the stories of the tradition.

I find one of the intriguing things about Douglass, a truly important point. He did not want to leave the oppressors behind, condemned. He wanted everyone to come into the kingdom of righteousness. While his universalism was always in potential, it was there. He believed everyone could step into righteousness, into freedom.

All we have to do is join with the poor, the lost, the left behind. A terrible invitation, no doubt. But it opens doors into mystery and grace and possibility.

Frederick Douglass’ life was a physical expression of the Exodus story. With the advantage of being real. He made mistakes. He wasn’t always wise. And yet he persisted. He called us all to better angels. He called us all to a religion that was grounded in human liberation. Specifically, he called us into a freedom that was characterized by holding each other up, by mutuality, by respect, and even by love. Freedom is letting go of what hurts and poisons; and embracing our radical interdependence.

We face terrible times. Maybe we always do. We need moral compasses to guide us, and exemplars to show us how its’ done. On this day, one hundred and twenty-seven years after he died, Frederick Douglass continues to show us how we might walk, and where. It’s about freedom. We do it in this world, or it doesn’t happen. Freedom. We do it together, or it doesn’t happen. Freedom.

An amazing gift. Thunder and lightning.

May we take it up and use it.

Amen.