This is the anniversary of Zen teacher Issan Dorsey’s death on the 6th of September, 1990. I’ve written appreciations a number of times, often expanding over the years on something started a long time ago.

Here, after my brief bio of the roshi, with permission I include Ken Ireland’s appreciation of Issan first delivered at Maitri Hospice, which Issan founded, on the twentieth anniversary of Issan’s death.

Tommy Dorsey, Jr, was born on the 7th of March, 1933, in Santa Barbara. The youngest of ten, he was raised in the Roman Catholic tradition. He dropped out of college and joined the Navy, only to be discharged when discovered in a relationship with another male sailor. Tommy wound up in San Francisco where he became a drag queen, and an occasional prostitute. He also became addicted to methamphetamines. His general trajectory was not good.

Then the rise of the hippie movement sparked his latent interest in religion. There was a brief psychedelic period. And at some point attracted to Zen, he started sitting with the Japanese missionary Shunryu Suzuki, Roshi. He gave up drugs and moved into the San Francisco Zen Center. In a delightful biographical sketch of his life published by Lion’s Roar Kobai Scott Whitney writes:

“Issan claimed never to have read a single book from cover to cover, except for one: Suzuki Roshi’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. Through-out the late 1970’s and 1980’s, he moved through the world of the San Francisco Zen Center like an angel in tabi socks, as graceful and outrageous as the stage-wise drag queen he had been before meeting Suzuki Roshi.

“Unafraid to acknowledge his long history of drug use, cross-dressing and prostitution, Issan Tommy Dorsey served as a kind of fringy shaman to the uptight and elitist Zen Center community of those years-a community with an atmosphere that actor and writer Peter Coyote once called “high Episcopal.” Tommy had always been comfortable in the borderlands of respectability and could serve to welcome anyone to Zen Center, no matter how odd they seemed to the broader sangha. This benefited individual beginners whom Issan could usher through the sometimes unwelcoming veneer of the Page Street City Center. It also helped the sangha, since Tommy’s success in adjusting to the rigors of Zen training proved to them that meditation practice could benefit anyone.”

When the Gay Buddhist Club was formed Issan thought it silly. Zen is Zen, after all. And he was pretty committed to the Zen Center itself, eventually serving as director. But, he soon found himself drawn in, and quickly into leadership for the group. Eventually it was reorganized as the Hartford Street Zen Center, and Suzuki Roshi’s successor Richard Baker Roshi ordained him as a priest and put him in charge. In 1987 in the midst of the AIDS crisis the group started Maitri Hospice and Issan brought their first resident, a man named J.D. into their small community. Maitri would be America’s first Buddhist hospice.

He worked tirelessly serving both the Zen community and the young men dying all around. That strange combination of outrageousness, sweetness of character, welcoming personality, and deep, deep Zen practice attracted men and women, gay and straight. While his own death came as no shock, it was felt as a loss to Hartford Street and the Castro, the Zen Center, the City of San Francisco, the Bay Area, and in some mysterious way, the world. Someone remarkable had passed through.

People often say as Issan is increasingly recalled as something of a Zen saint, a genuinely holy figure, that it is important to remember he was a person with a boatload of personal problems. Those who knew him will then recount some foible or another. And he did have a lot of them. He was, after all, a man with a past. But, in that telling quickly, quickly, the stories of his heart and gentle wisdom, and most of all his love for everyone he encountered would take over.

Issan Dorsey was someone we can all look to as a guide on the way. He really is one of the signal figures of the founding of Zen in the West. He ranks somewhere with Shunryu Suzuki, with Jiyu Kennett, with Taizan Maezumi, with Robert Aitken, with Maurine Stuart, with Dainin Katagiri, with Kobun Chino Otogawa. The gathering cloud of witnesses to the great Zen dharma way, and who would make it Western and American. That crowd.

I only met Issan once. I represented what was then called the California Diamond Sangha at his mountain seat ceremony, installation as abbot of Hartford Street. It was a crowd. I had gotten lost going to the center, then had trouble parking, and only arrived in the building just before the ceremony, when I was escorted to a not quite appropriate spot to put on my robes. I recall Baker Roshi walking by on his way to begin the ceremony and giving me a look that seemed to say, what are you doing, and why are you doing it there? Then, right behind him, Issan also walked by, looked at me, stopped, turned full in my direction, put his hands in gassho and gave me a deep standing bow. As he raised his head, he smiled, winked, and turned to the matter at hand.

I’ve never forgotten his pause, his turn, his bow, that smile, or that wink.

***

One bright afternoon, Isaan was walking down Hartford St. towards 18th with Steve Allen and Jerry Berg. They were headed to the hamburger place that used to be right next to Moby Dick’s, close to the corner. That might not be important unless you want to know if Issan loved hamburgers—he did—but you have to know that Steve is a Zen priest, a close friend of Issan, his dharma heir, and the first Executive Director of Maitri. Jerry Berg was an early supporter of the hospice, a successful lawyer and prominent leader in the gay community.

As they walked, Steve and Jerry were talking about possible legal structures for the hospice while Issan lagged behind. He noticed a bottle lying on the sidewalk and bent to pick it up. Yes, any rumors that he was an incarnation of Mr. (or Miss.) Clean are well founded. But when he noticed that the bottle was rather beautiful and might be worth keeping, he took out the rag that he kept neatly folded in his monk’s handbag, and began to polish it. Suddenly, a Genie appeared! It had to be a Buddhist Genie, a Bodhidharma look-a-like, with a shaved head, droopy ears and a bright robe. The Genie looked at Issan and Issan looked back, a staring match of wonderment. Steve and Jerry turned around to see what Issan was holding Issan up and stopped dead in their tracks.

The Genie spoke the time honored script of genies: “Because you have freed me after many lifetimes of being cramped-up in that god damned bottle, you, yeah, I guess all three of you, get one wish. It’s just one so you’d better make it good.”

Steve didn’t hesitate: he knew his Buddhism and asked to be released from his karma and enter Buddhahood, or nirvana, or the Pure Land, right there and then. Just as he was about to raise his palms in gassho, the traditional gesture of respect—poof, he was gone.

Jerry thought to himself, that was powerful magic. I’m going for it. I’m not getting any younger so how about a great life in a heaven modeled after Palm Springs—but without the humidity—endless pool parties, rafts of handsome men, an eternal nosh that never made you fat? As he smiled and waved good-bye—poof, he disappeared too.

The Genie turned to Issan who was left standing alone—it might have been wonderment on his face, maybe just a bit puzzled. The Genie said, “OK, honey, it’s your turn, what does your little heart desire?

Issan didn’t hesitate, “Get those two numb-nut girls back here. We have a hospice to run.”

Tonight we’ve come together to remember Issan Dorsey.

Jana just lead us in an ancient ritual to call upon the powers that guard the unseen world from which we can still feel Issan’s presence from time to time. Perhaps we can also allow ourselves to enter that world tonight to see him, to hear him, and allow ourselves to be inspired and get the strength we need to live our own lives as completely and authentically as we can.

There are many reasons why we might want to remember him—for most of us who knew him and loved him—we cherish who he was for us, the way he moved through the world. We remember the kindness of his actions—and his great one-liners.

For those of us who meditated with him, he inspired us by his depth of his practice—the way that he carried his understanding of the Buddha’s teaching into his life seamlessly. The man who sat in the zendo was not one bit different from the man who had a martini at the gay bar around the corner or who listened carefully to everyone’s point of view during a staff meeting.

For those of us who worked with him, we knew that his projects had heart. No matter how complex they became when we tried to made them real, no matter what problems or difficulties arose, Issan always directed us back to the heart of the matter—love, compassion, service.

For those of us who only know him by having read about him or heard about him, or having worked at Maitri, you still know him. He didn’t write any books himself, but he left a real example of how humans can look after one another with love and friendship. Here it is! We’re standing in the middle of it right now. And that is perhaps the best way to know him, by trying to look after one another throughout our entire lives in ways that make difference and bring us closer together.

Tonight we are going to try to bring him back into our lives as a way to honor him, and thank him, and be inspired again by his vision for home and hospice for people with AIDS.

I have heard more than 100 versions of this story over the years: “if I hadn’t met Issan at the door of City Center or Tassajara, if he hadn’t really hugged me, told a joke, said a few words that calmed me down immediately, I wouldn’t have struck around—I wouldn’t be here today.” He was a man with the ability to find those few words that you needed to hear in the moment, words that came from the heart, words that gently cleansed the sting of whatever was troubling you. He was a man with an open heart. He was truly a Zen priest.

I have moments when a single phrase that Issan said to me just comes up, for no apparent reason. He had an uncanny ability to take complex issues and say what was important in a few words. Some people can only understand an issue presented in its most simplistic form. But Issan’s few words didn’t show any lack of understanding. When I worked with him (and particularly when I talked about my meditation practice with him), I felt his few words go very deep.

And for gay man like myself, part of the large influx to San Francisco of gay, lesbian and bi men and women during the 70’ and 80’s who were, by and large, alienated from the religious practice of our mothers and fathers, a simple, light-hearted message that went to the heart of the matter was perfect. And if it were delivered with perfect timing and some campy trimmings, all the better.

Once at a staff meeting I was fretting over something that was stamped “urgent” (it seemed as if almost every item in my to-do pile had some red flag, screaming “right now,” “get me done”). Issan just reached out, touched my hand and said, “We’re at war. I’ve been at war, and it’s not fun—well not always fun. We can still have some parties.”

Back in 1988 and 89 sometimes more than a hundred men a week were dying from the effects of HIV/AIDS. It was a disaster the dimensions of which the nation as slow to recognize. There wasn’t time, money or resources to do everything that needed to get done, much less do it perfectly. Somehow, I knew that if I could just focus on what was in front of me, and get that done, it usually turned out to be exactly what was required. And for those of you who know me, it’s something I still struggle with. Thanks Issan—your teaching continues.

And the story also reminds me that when you’re at war, you also find out quickly who your friends are. When the epidemic hit full force, after all the political posturing and bullshitting, our community found resources within itself to care for a tragedy of unbelievable proportions. And we were helped by a huge number of generous men and women from the wider community who saw beyond whatever labels were being thrown around then—forgive me if I’ve blocked them out—and stepped forward to ease the suffering of some fellow travelers.

Issan saw Maitri as much more than just a Buddhist hospice, though it was deeply Buddhist to its very roots. He shaved his head, and wore a Soto priest’s patch-work robe, he bowed and chanted in Sino-Japanese, but he understood very clearly that real wisdom, what we call Prajñā, is not the sole property of any religion.

I want to tell a story about the Mass that my friend, Joe Devlin, a Jesuit priest, said in the zendo at Hartford Street early in 1990.

I had asked Joe to come by and say Mass for the Catholic men in the Hospice. It was a Saturday evening, and Joe was due to arrive at 5. I was scrambling, assembling a few basics, actually just the essentials, bread, wine and a clean tablecloth for the dining room table. Issan, who was at the time in the final stages of HIV disease came downstairs in his bathrobe, to ask when “Father Joe” was due to arrive and see what I was doing. After I explained, he said with a big smile, but firmly, “Mass will be in the zendo, not the dining room.” Then he took over and directed all the preparations with the same care that he would have given to a full-blown Zen ritual. He went back upstairs and when he came down again, he was dressed in his robes. He greeted Joe at the door with a hug and kiss, thanking him for coming and telling him that Mass would be in our chapel, the zendo.

Issan and five or six of us sat in meditation posture on cushions while Joe improvised the ancient catholic liturgy, beginning with a simple rite of confession and forgiveness. When it came time to read from the New Testament, Joe took a small white, well-worn book out of a pocket in his jacket, and said that his mother had told him that the story he was about to read contained all the essentials for a true Christian life.Then he read from the gospel of Luke, chapter 11, the parable of the Good Samaritan. For any of you who need a refresher course in New Testament studies, this is a story about a man who is robbed, taken for everything he has, savagely beaten and left by the side of the road to die. All the people who might have helped, even those who should have helped, chose to walk on the other side of the street when they saw him—except for the Samaritan. Now the Samaritan in Jesus’s day was the guy whom good upstanding members of the community might have called the equivalent of “faggot” or “queer.” He was an outcast, but he was the only person who actually stopped and took some real action to help the poor fellow out. So Jesus teaches here that real love is shown through actions, not words.

The next morning—Sunday mornings were the usual gathering of the Hartford Street community—Issan began to talk about Fr. Joe and the liturgy. He was exuberant. He had fallen in love with Luke’s parable, and Joe. He turned to me and asked, “What was the little white book that Fr. Joe read from?” Startled, I said that was the New Testament. “Oh,” said Issan, “it must have been in Latin when I heard it as an altar boy—or something, but it was exactly how we should lead our lives as Buddhists.” He then said that during the Mass he had the experience of really being forgiven and that the experience had allowed him to feel peace, even appreciation for his early religious training.When Joe and I had dinner together the night before he flew back to Boston, I told him what Issan had said. A few days later, the small New Testament that had been in his jacket for years arrived in an envelope addressed to Issan. Before Issan died 6 months later, during one of out last meetings, he asked me to thank Joe again for the zendo mass after he was gone. I did. And that New Testament which passed from the pocket of Joe’s jacket to Issan’s spare bookshelf at Hartford Street to my altar, I have since passed on to another person who asked a dharma question about one the stories in the gospel of Jesus.

If I were to give a nice sounding Buddhist name to the next story, it might be something “like there’s nothing too small that you can let escape your attention, even if no one’s going to notice,” but I think that “They never get the pleats right” tells the story better.

When Maitri was on Hartford St., we carried on a full meditation schedule plus running the hospice. One Saturday we were sitting meditation from 5 in the morning till dusk. Issan was not sitting, actually he was in bed and his doctor, Rick Levine, was monitoring a fever that had spiked at about 103 the previous day. That evening, he was to preside at the wedding of two men, old friends, at the Hall of Flowers in Golden Gate Park. 20 years ago Issan married same sex couples in the religious tradition of Soto Zen—long before the issue of gay marriage exploded, Prop 8 passed, was then voided—well, you know that story.Sometime after lunch I noticed his white koromo, fresh from the dry cleaners, hanging on the coat rack in the hallway. The koromo is a simple kimono style garment that a priest wears under the Okesa, the Buddha’s robe that is worn over the left shoulder. With the full robe, not much of the koromo is visible. It’s really like ceremonial underwear.

I went back to my cushion in the zendo. When I came up stairs again about 3:30 to fix tea before the last block of sitting, there was Issan in the living room, in his bathrobe, with a little head band, and swear dripping from his forehead behind an ironing board. He was ironing the koromo fresh from the dry cleaners. I stopped on the stairs and I had to stop myself from telling him to get back to bed, follow his doctor’s orders and save his strength. I am sure he saw the shocked look in eyes. He turned to me, chuckled and said, “They never get the pleats right.” I certainly wasn’t going to argue with a man who was obviously in a deep state of meditation.

He did preside over the wedding and it was fabulous. Steve and Shunko who were also part of the ceremonial team, came home relieved though complaining about the two husband’s gift list of toasters and table service, “Nothing for the Hospice!” Issan was quick to diffuse them—it was a very special day for the couple who were setting up house together for the first time.

And here is another lesson I learned from Issan, one that took me a long time to digest and one that I still struggle with: there is always enough money to do what you need to do. And most likely, in the best of circumstances, it will be just enough, not a penny more or a penny less. When you are tight, (or if you’re tight) it’s probably time to reorder your priorities.

Over more than 2 decades, Maitri has rethought its priorities many times and revised its budget accordingly. New drugs have increased the longevity of persons with AIDS, and the death rate has plummeted. But new issues have arisen: some people can’t manage the rigorous schedule of drug administration and need training; partners and family who are caring for people with more limited abilities imposed by HIV need a break to care for themselves and thus Maitri’s respite care program and training in self-care.

The new director along with the board will continue to adapt and reinvent Maitri’s programs to maintain the two hallmarks of Issan’s vision: quality care and a true home. This is also a place where we might dedicate our energy tonight: to support them as they chart new directions and promise to do what we can when they ask for whatever they’ll need, ideas, resources and of course money.

In the last year of Issan’s life, a local musician with some spiritual roots had a minor hit. I’m talking about Bobby McFerran’s, ‘Don’t Worry, Be Happy.” Issan loved the song and sometimes would hum or sing a bit of the lyric and then say, “that’s good but I think he should add, ‘Just do the best that you can.’ We aren’t asked to do more, but that’s more than enough.”

So I’ll end my stories here with the refrain: “don’t worry, be happy, do the best that you can.” Issan, you showed us whatever you can do with your own mind and heart is more than enough to make a lasting impact in the world.

And now finally to wrap it up, I’m going to return to my Buddhist joke:

Issan knew that he wasn’t a one-man show—even in his drag days he didn’t perform alone. He was not the Lone Rangerette, or Mary Tyler Moore facing adversity with a smile and disarming off the wall comments though he had some of that quality. Actually if I had to pick TV character for him it would be Rue McClanahan who played Blanche Devereaux in the “Golden Girls,” one of his favorite TV shows. So I can hear telling me, “Ken, be a sweetheart, and thank everyone.”

All of us are intimately connected with one another. The inner workings of an organization as complex as Maitri are also connected to us. As I look at this web, this net, the list of people whom I should thank is longer than the list of names I am going to read. But I will take a few minutes to read some names and I ask you to join me in acknowledging these people and offering them our deep gratitude.

Steve Allen, who returned from nirvana to help Issan (in his case, an innovative temple in Crestone Colorado), represents the many Buddhist practitioners who interrupted their own lives and practice to be with Issan as death approached. They include Steve’s wife, Angelique Farrow, Shunko Jamvold, David Bullock, David Sunseri, David Schneider, Lucien Childs, Zenshin Phil Whalen, Angie Runyon, Paul Rosenblum, Rick Levine, Zenkei Blanche Hartman, Issan’s teacher, Richard Baker roshi, Kobun Chino roshi, John Tarrant roshi, Joan Halifax, Frank Osteseski, Ram Dass, Wendy Johnson and the gang from Green Gulch who brought cartons of food every week for the kitchen, Rob Lee whose photographs you see displayed here tonight, Tozan Mike Gallagher and Joshi Paul Higley, men with HIV who were ordained as zen priests, who practiced at HSZC and added enormously to the richness of our practice. I’ll humbly include myself among this group. I began my formal Zen practice at Hartford Street/Maitri Hospice and that has been an enormous gift. The privilege of being allowed to do this work changed my life.

Jerry Berg was a wonderful human being and fabulous leader in the San Francisco gay community. He can stand for all the men and women who were not members of the Buddhist community but generously stepped forward into important roles that ensured the success of Issan’s vision. They include, Richard Schober, Will Spritzma, Richard Fowler, George Heard, Jim Hormel, Tim Wolfred, Bill Musick, Tim Patriarcha (who is Buddhist), Tova Beatty, Maura-Singer Williams, Christine Vincent, Lynn, our head nurses, beginning with Jan Clark, and Anne, Visiting Nurses and Hospice, now Sutter-Home-Health, and Glo Newberry-Smith; I want to thank the hundreds of individuals who gave whatever they could afford, whether time or money, Jim Hormel, Al Baum, Jon Logan to name just a few; our volunteers, board members, Traci Teraoka, Sally Anne Campbell, George Stevens, Boone Callaway, Anne O’Driscoll who cooked great hearty meals, Jane Lloyd who cut hair, Bob Gordon and Bill Haskell, and perhaps a hundred more wonderful men and women who gave of themselves to be with our residents; I want to thank all our CNA’s, Gary, Ichto who’s been with Maitri for more than 20 years, Joyce Cabit, who has also been with us almost from the beginning to name just a few; I have to thank the many small businesses that helped with services, like Marcello’s pizza. Friday night pizza dinner was a highlight of the week and allowed the cook a well deserved night off. I also want to include the designers, craftsmen and carpenters who helped us covert 61 Hartford Street into a hospice, only mentioning 2, Alberto, and Juan (Issan thought you were about as handsome as men come), and I have to thank those who transformed the building where we’re standing now, especially Sylvia Kwan and Joseph Chance. You helped Issan create Buddhist heaven.

And finally I want to thank the almost 950 men and women who made Maitri their home during the last months and days of their lives. You allowed us the privilege of being your servants, and walk with you as you completed your earthly journeys. Your generosity taught us lessons we can never forget. You changed our lives.

The list goes on but I have to stop here. To all the many people and organizations who’ve shared and contributed to Issan’s vision over nearly 25 years, our heartfelt thanks.

Thank you all for your kind attention. Thank you, Issan. As is said in the traditional closing prayers for celebrations like this: May the teaching of your school go on forever. May all beings be free from suffering and the causes of suffering.

***

To read more reflections about the life of Issan, see some photographs, read his dharma talks, go to Ken Ireland’s Record of Issan page.

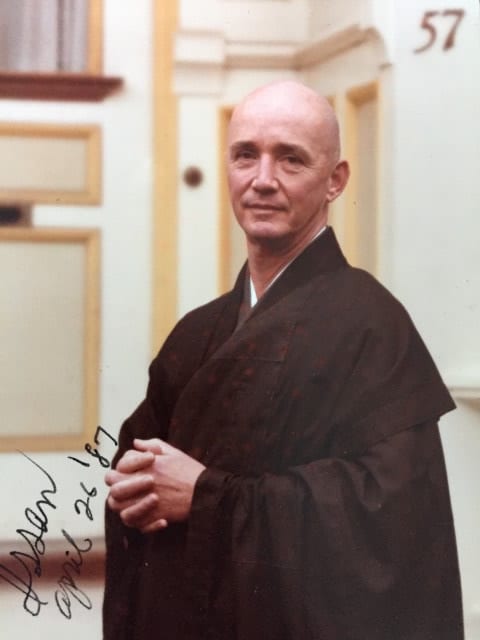

Issan Dorsey, Zen priest and abbot of the Hartford Street Zen Center.

Teacher. Founder.

American Zen exemplar…