THE GOOSE IN THE BOTTLE

Exploring the Possibilities of Interspiritual Dialogue

A Sermon delivered at the

First Congregational Church of Long Beach

United Church of Christ

20 November 2022

First, thank you so much for welcoming me into your community. If you don’t know we Unitarian Universalists and especially the Congregationalist roots of the United Church of Christ share a history. And even today you might imagine a Venn diagram for the UCC and the UUA while largely going in divergent directions, continue to have a substantial overlap joining us not simply historically. But also sharing a radical embrace of personal freedom in walking the spiritual path, along with a profound sense that the spiritual must always have practical and social consequence.

As to those differences. Your touchstone remains that wonderful story of Jesus, held more deeply or lightly for each person within your community. There is that radical freedom in understanding what this means. But Jesus and the Christian tradition writ large is your touchstone. While to know what a Unitarian Universalist believes, well; you have to ask.

With that let me briefly describe my spirituality. An Episcopalian colleague once observed, “James, you’re a Zen Buddhist who loves Jesus.” Of course, there’s more to it than that. But, if you add in a pretty rationalist and naturalist bias, you might see how I ended up a UU. Something of a spiritual mongrel, and frankly, few others would have me. Maybe, you all. But not many more than that.

Over the years of my adult life Zen Buddhism’s core insights and practical disciplines have remained a constant. Still, over the last years, I find the heartful Christian way ever more important within the spiritual stew that is my life. I am, I guess, a walking interfaith dialogue.

Which brings me, if briefly, to the whole idea of interfaith conversations. It can be personal, I’m an example, but hardly that rare. But it’s also a communal project, it has its own disciplines, and it brings many rewards. Recently a colleague cited the poet and musician Nick Cave, who tells us “(A) good faith conversation begins with curiosity, gropes toward awakening and retires in mercy.”

Curiosity is key. I’ll return to that. And I’ll come back to that lovely word “awakening” as well. But first a small consideration of what Cave calls “retiring in mercy,” the fruits of this project. Mercy. Another lovely word. I understand our English term derives from the Latin and means roughly “the price paid.” Big in Christian theology, of course. Bottom line it’s a gift. A kindness. Generally understood as coming unmerited, unearned. It’s something just given.

Mercy brings a certain peace to the matter. It allows us to look beyond our own concerns, to see bigger pictures. Which has a certain healing quality to it for us as individuals. And often it shows us how to be of use in this poor, beautiful, and broken world. One tends to share mercy. Not always, but it lends itself to being shared.

With that, let’s consider awakening. I’ve always liked it. It suggests there are truths that are lost in the slumber of ignorance and self-centeredness. Which vanish like morning dew when we wake up. It’s another word like mercy that doesn’t seem to require much on our part except letting it happen. I won’t go far into it here, but I find the underlying questions around the current political term “woke,” an example of that image shared in our communal lives, and the gifts it offers. Do we notice other people’s hurt? Do we see ourselves waking from being part of continuing that hurt? Waking up is noticing what is already there. And it brings healing.

But. And. What is it we actually wake up to within this spiritual enterprise? This is an important question, isn’t philosophical, it is visceral. And. This is where the multiplicity of perspectives coming to the same common concern, our human suffering, spiritually and materially, and what might be done, begins to reveal itself. There are Jewish ways, Christian ways, Muslim ways. Hindus and Buddhists offer ways as well. And that only begins a list.

Looking at more than one can begin to clarify the matter, can even help us on our own individual paths of awakening. This is the real point of interfaith conversations, as I see it. To see how this might work, to give an example in our brief time here, I’ll stick to Christian and Zen Buddhist. And how considering both we might find our own individual awakening, as well as hints to how we might bring healing to the world.

Christians wake to the “kingdom of God.” The word we we translate as reign or kingdom is “basileia.” The Biblical scholar Walter Wink suggests that “basileia is used in the New Testament to mean a world order exemplified by the life of Jesus. I find that a delightful interpretation of that reign or kingdom as a word for a world that is partially in the future and partially here and now, which expressed within the story of Jesus. And which through that lens, looking at Jesus and his life, especially his actions and teachings, can be restated as a or the “Way of Unfolding Love.” We look at Jesus, the Jesus who lived and taught and suffered to see the kingdom that invites us, to see a way of unfolding love as our intimate path. And as what awakening looks like.

So, awakening. Waking into unfolding love. Accepting differences. Seeing hurt. Not pretending things that exist don’t because its inconvenient or shameful. But relentlessly leaning into unfolding love. Which brings, as I’ve already alluded to, another unfolding, unfolding healing.

So, what about Zen and its awakening? What’s the other angle on the matter?

Traditionally Buddhism is very academic. It looks at problems, it diagnosis their causes, and it prescribes treatments. The great image of the Buddha is as a physician. A core message the Buddha conveys is that we mistake that which is passing for something permanent; and within that misperception much of human ill emerges. Classic Buddhist meditation is about that treatment for our ills, paths of moral conduct and incredible meditation disciplines.

Then Buddhism came from India to China, and encountered another ancient culture, and especially the wild nature mysticism called Taoism. Almost immediately things began to happen. An example of interfaith conversation. Buddhisms, there are several, Buddhisms, which tended to center in the head began to experience the whole body.

Zen is a Chinese expression of Buddhism. And in Zen awakening began to be found in stories, and play, serious play, but play nonetheless. (Parenthetically, Zen is the Japanese pronunciation of the Chinese word Chan. The word points to a school focused on the disciplines of meditation, but colloquially it also means awakening.)

A few minutes back Reverend Anne told that wonderful story about a rooster. There’s actually a traditional koan in the Zen way that’s very nearly the same, although to a slightly different purpose. So. Koan. One more word. The last one for us to unpack here today. It’s a Zen term. And it’s a major way spiritual play happens in Zen.

A koan is an object or theme in meditation that is explored together with a spiritual director. It’s part of a discipline that is more than a thousand years old. I’m sure you’ve heard of koans if only in passing. “What is the sound of one hand clapping” is maybe the most famous in our popular culture. Although for comparison, there’s another saying that gets touted as a koan, “If a tree falls in the woods and no one hears, is there a sound.” That is not a koan. It’s a conundrum. And there’s a touch of wit in it. But that’s all.

The story about the sound of a hand is a koan as an assertion about some aspect of reality, a pointing to what the awakened world looks like, presented together with an invitation to experience that reality here and in this moment. Koans are about awakening. Always. They’re not tricks. They’re not jokes. At least not in a conventional sense. Koans point, and they invite.

Here’s what I believe. I suggest we can honestly see koans as invitations to our personal, our individual awakening into unfolding love. Two angles on something deep. With awakening the tradition that brought us there flavors our insight, Buddhist, Christian as examples. But the insight is, well, a direct seeing into what is. It’s waking up. And we all can wake up, whatever our condition. Whatever our religion.

Here’s the koan that the echoes the rooster story. “Once a woman raised a goose in a bottle. When the goose was grown, she wanted to get it out. How can you get it out without breaking the bottle?”

Now the big difference in the two stories is that in the traditional Western folk tale, the bottle is broken. And we discover the poor rooster has been malformed by all that time in the bottle. An important point. A harsh truth. As we look within ourselves, we get hints about our own lives, and how we’re shaped by our environment as well as by the decisions we’ve made throughout our lives. Shaping and misshaping. A good lesson. One we might wisely heed. It can bring its own kind of healing.

But here’s another question. What happens when we don’t get out of the bottle, when we continue to be constrained? From before our births, we’ve been shaped to fit our particular bottles, yours and mine. Constrained by all the conditions of our lives. You can make your own list. And, it’s important to note, this shaping is not all bad. Some of it is actually very good. But nonetheless they shape and contain us. And much of this is not good. Some is shameful. And it is what we are.

So, how does this koan gather us in with our fears and our dreamings? How does it show us our possible awakening? How do we find that unfolding love in this life that we live? If you will: where is Jesus in this story of a goose and a bottle? The Jesus that can shape our lives into freedom and awakening?

Now, I think it’s interesting that there’s a companion koan to the one about the goose in the bottle. Gathered in our Zen collections of miscellaneous koans as case six. “You find yourself in a stone crypt. There are no windows, and the door is locked from the outside. How will you get out?”

Instead of a bottle we’re in a stone crypt. A tomb. A grave. Mortality is now in the play. A grave with no exit. So, what do we do? Christians can work with this story. It has something to do with Good Friday and Holy Saturday. And it hints at an Easter. If. If we see that story as about us, you and me. And our own awakenings.

Here’s the secret. The bottle is named. The crypt is named. As we see the truths of our lives, even in our sleep, we find a certain power. As we notice ourselves, we find the power to wake up. If we see it, if we own it, whatever it is, good and ill; then miracles can happen. The waters are troubled. And mountains shake. And our unfolding love is named, as in today’s psalm, as God. As our heart. Yours. Mine. The one who stills the waters, who breaks the weapons of war.

And it’s specific. Specifically, the God named there, the god of unfolding love is found ‘within.” Yes, found among, as well. But that’s for another conversation. This is about what we find when we look within. Your within. My within. In the specific of our lived lives. Here we find, or can find, God is with us in the bottle, with us in the shape of the bottle that continues when it is broken.

This God is with us in the crypt, the one that cannot be escaped. Here’s what our awakening wakens to. Wherever we are, God is with us. As the prophet Muhammed said, closer to us than our jugular vein.

Of course, other questions flow from that. Whether we’re Christian or Buddhist or, well, any story of faith and hope. What is the next step? What about after waking up? If we are born into a way of unfolding love. If we taste it, if we notice it, well, then. What are we going to do with it?

Just like a koan. An assertion about reality, and an invitation.

A small question to consider from a visiting friend.

Amen.

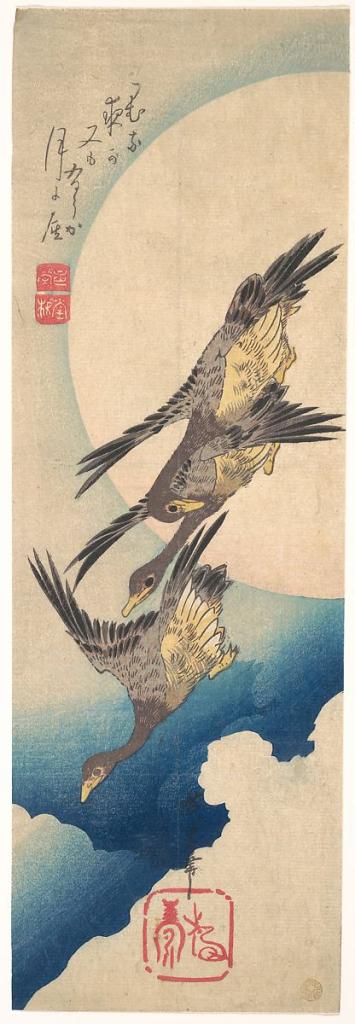

The image is by Utagawa Hiroshige