I recently saw a video clip that described how nineteenth century European immigrants brought Christmas to these shores. It was a reference to how the Puritans had outlawed the holiday, and that it was not observed from the late seventeenth and throughout the eighteenth century.

The immigrants were very important. Essential. But, it required one more step to be absorbed by the culture at large. And, it was the Unitarians, who gave the whole thing the veneer of respectability which was critical for the celebration to jump from a private family observation among immigrants to the public religion it quickly became.

“Unitarians didn’t just inherit Christmas from the orthodox Christian sects,” Doug Muder tells us. “To a large extent we invented it, or reinvented it. For years the orthodox didn’t know what to do with Christmas. Easter was the big religious holiday. In England, Christmas looked more like Saturnalia than anything Christian. The actual caroling tradition was more like trick-or-treating than the way we picture it now. Rowdy mobs of the poor would stand outside the houses of the rich and intimidate them into offering food and drink.”

Mr Muder concludes, “The Puritans hated the whole idea so much that the Massachusetts Bay Colony would fine you for celebrating Christmas.” And that’s how it was for a very long time.

Finally, however, Christmas came to New England. As I mentioned there were various immigrants who quietly observed the holiday. But, there still needed that turn into the larger culture. Well, we can even put a date to when that happened. Obviously with such things and with multiple events going on picking just one is a bit problematic, but, I think this is a pretty good marker. It was in December 1832, when the Reverend Charles Follen placed a tree in his Cambridge, Massachusetts home, and the family decorated it. I see him as the bridge. In fact the Reverend Mr Follen was himself an immigrant, from Germany, but as a minister and professor at Harvard, he carried the full weight of New England respectability.

And, there were no doubt other Christmas trees going up here and there, even in “respectable” homes. But, there was one more thing here. The Follens were visited by the English journalist (and Unitarian) Harriet Martineau, who wrote:

“The tree was the top of a young fir, planted in a tub which was ornamented with moss. Smart dolls and other whimsies glittered on the evergreen and there was not a twig which had not something sparkling upon it… I mounted the steps behind the tree to see the effect of opening the doors. It was delightful. The children poured in, but in a moment every voice was hushed. Their faces were upturned to the blaze, all eyes wide open, all lips parted, all steps arrested. Nobody spoke, only Charley leaped for joy…”

Captured charmingly on paper, the image caught many a family’s imagination. And from there, there would be no turning back.

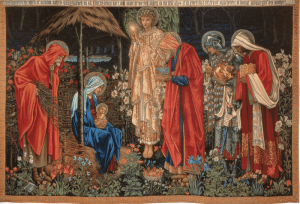

Now, there was a reason the Unitarians did this beyond the joy of sticking a thumb in the eye of authority, as much fun as that can be. Unlike Easter, tied up as it is with stories of mythic events playing out on some cosmic scale that make very little sense when measured against our actual lives, Christmas is about a child being born and how that tiny, tiny event contains everything human beings need to know to find a way to hope and joy and possibility. The bells and whistles, the angels and wise men are window dressing. The story is the miracle of possibility in a single birth.

I like to note the fact that Ms Martineau was visiting Reverend Follen, not to see that tree, but to discuss the organization of abolitionists. And, me, I find the struggle for human liberty, real, tangible physical liberty being a subtext for the witnessing of that wondrous tree something worthy. Deeply, deeply worthy.

Back when I was serving at the First Unitarian Church in Providence, in our annual Christmas pageant the Christ child was usually a baby born close enough to Christmas to be a small baby. But we didn’t worry too much beyond that. one year the baby Jesus was a little girl, another year the baby Jesus was twins. I remember when baby Jesus had two dads. I also recall that year when there were three families who had their babies within days of each other, and we decided, well, we have three aisles, and so we proceeded to tell the story with three holy families.

Ordinary people as miracles. Ordinary hope as a miracle.

I find this resonates with my Buddhism, which is also a tradition of the miraculous ordinary. Of bringing the mystery right into our ordinary lives.

So, the Christmas season is a gift for all of us as the season of ordinary hope, of our body knowing of the light inside the dark. And one more thing. I think ownership of the holiday cannot even be limited to one faith tradition. It is too powerful. It is to universal. It is too ordinary. Ordinary. Just like a little girl baby Jesus. And in that noticing maybe we can find our own miracles. Out of this ordinariness brought to us by a child, brought to us by an enemy who refuses to fight brings with it a call to work, to the real work of our lives, to the work of Christmas.

The poet, theologian, mystic Howard Thurman sings to us of this work of Christmas, of ordinary miracles:

When the song of the angels is stilled,

When the star in the sky is gone,

When the kings and the princes are home,

When the shepherds are back with their flocks,

The work of Christmas begins:

To find the lost,

To heal the broken,

To feed the hungry,

To release the prisoner,

To rebuild the nations,

To bring peace among brothers,

To make music in the heart.

No wonder the wise continue to seek him.

The secret hope of all hearts.