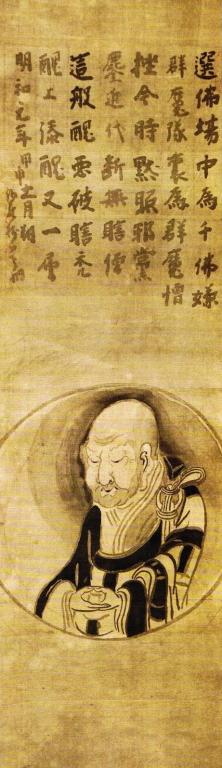

self-portrait, 1764

(A dharma talk delivered at the North Carolina Zen Center sesshin on the 19th of October, 2023.)

A couple of weeks ago I was privileged to attend the first in person gathering since covid of the now venerable American Zen Teachers Association. The meeting was held at Great Vow Zen monastery in Oregon. I’d hoped to see Teshin there, but he was gallivanting around Japan.

For me these gatherings are mostly meant to be checking in with old friends and companions, people who’ve walked similar dharmic paths for years and years. And I think that’s true for most people who attend. But there’s also a component where we are hoping to improve our skill sets as teachers. Of less importance to me these days as I begin to wind down that part of my life, but it’s still there, and there is still so much to learn.

I was especially taken with the panel presentation on just sitting, Zen’s base line spiritual discipline. Mokusho chan, shikantaza, silent illumination, just sitting; lots of terms, usually, although not completely in alignment.

What caught me was near the end of some very insightful observations about the nuances and details of the practice was when one of the presenters, a Zen priest and academic, spoke. After discussing some of the nitty gritty of guiding practitioners on this path, she concluded with, and I think this is close to a direct quote, “Of course, zazen, Zen meditation, is really a koan.”

Now even among Zen teachers the word koan is often used to mean a thorny problem. And there was a bit of that in what she was saying. But she knows the correct usage of a koan as a profound matter to be made clear as the late Aitken Roshi once said, or as an assertion of that deep matter together with an invitation as I usually prefer to explain koan. The powerful tool of spiritual transformation unique to the Zen schools.

I found this really important. Zazen, mokusho chan, shikantaza, silent illumination, just sitting are words for a koan.

As seated meditation is the baseline practice of our way, and as I’ve seen a lot of people struggle with it, I believe it would be helpful to unpack the koan of just sitting a bit here today.

This discipline that is Zen meditation has evolved from classic Buddhist meditation disciplines associated with Gautama Siddhartha. It comes to us blending Vipassana or “insight,” and Shamatha or “concentration.” It’s somewhat simplified from its Indian origins and then is washed through the whole of Chinese culture with some influences by way of Confucian spiritual culture and more from Daoism. Perhaps even more important Zen meditation is infused with the great insight of our original awakening. Like the discipline of koan introspection, just sitting becomes a unique gift of the Zen schools.

In his essay the “Method of No Method,” the Chan master Sheng Yen writes:

“This “just sitting” in Chinese is zhiguan dazuo. Literally, this means “just mind sitting.” Some of you are familiar with the Japanese transliteration, shikantaza. It has the flavor of “Just mind your own business.” What business? The business of minding yourself just sitting. At least, you should be clear that you’re sitting. “Mind yourself just sitting” entails knowing that your body is sitting there. This does not mean minding a particular part of your body or getting involved in a particular sensation. Instead, your whole body, your whole being is sitting there.”

Taking it from there, I’ve also found our great grand teacher Hakuun Yasutani gives a very helpful pointer.

“Shikantaza is the mind of someone facing death. Let us imagine that you are engaged in a duel of swordsmanship of the kind that used to take place in ancient Japan. As you face your opponent you are unceasingly watchful, set, ready. Were you to relax your vigilance even momentarily, you would be cut down instantly. A crowd gathers to see the fight. Since you are not blind you see them from the corner of your eye, and since you are not deaf you hear them. But not for an instant is your mind captured by these impressions.”

I would call this the mind of presence. It’s something rooted in our very humanity. Neuroscience suggests this self-awareness as an aspect of consciousness, arises in the brain in the insular cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the medial prefrontal cortex. Precisely how this works, or even it this is actually the right track, is not a settled matter. However, as important as knowing how it works is, Zen is a sophisticated spiritual technology applying the mind of presence to the deep matters of our being.

It shows us who we are.

The basic practice technical term for this mind of presence is hishiryō, which is variously rendered nonthinking, without thinking, and beyond thinking. I’m increasingly fond of the term before thinking. I’m not sure where the first usage of hishiryō comes from, but it appears in the Lotus Sutra and Faith in Mind, as well as in the classic Chinese Zen collection the Record of the Transmission of the Lamp. Which itself is a primary source document for the great koan anthologies like the Gateless Gate and the Blue Cliff Record. The term is most famously used by the thirteenth century Japanese Soto Master Eihei Dogen.

The principal document unpacking nonthinking, without thinking, beyond thinking, or before thinking for many of us comes from Dogen’s wonderful Fukanazengi. It comes to us in two versions. The first version is dated from 1233. Although it is clearly based on thoughts dashed off earlier. Carl Bieledfeldt suggests the second edition appears to date from 1243, a decade later.

The text is closely based on a Chinese document, the Zuochan yi written by Changlu Zonze which dates from the beginning of the twelfth century. Dogen incorporates substantial parts of that original, what today we would consider massive plagiarism. However, Dogen is in fact quite critical of the original manual, and definitely brings his own stamp to the matter. And with the version of 1243, the so-called vulgate version, Dogen is presenting his mature understanding of the practice.

And here’s where we meet the koan of just sitting. As I read the text in both versions, I see the matter of just sitting, of shikantaza straightforwardly being presented as a koan. For me it’s as plain as the nose on your face. In fact this is the critical key to understanding the entirety of Dogen’s work.

As I read Dogen, it’s obvious how deeply informed he is by koan introspection. It isn’t totally clear what the nature of his koan training was. What we know is that when he was studying was a transitional period where the huatou form of koan introspection, where one spends a lifetime with a single case, was beginning to transform into the study of lists of koans, one after another. Now, speaking as a person following a koan path, it seems obvious Dogen is deeply informed by the depths of the koan tradition, and not merely as a reader of Zen anecdotes. A koan informed insight is present on every page he writes. And often, I believe, it would be difficult to understand him if one is not familiar with the koan way.

However, the master is also critical of a one-sided koan practice. He was especially harsh with those who get lost in the sky castles that shadow the koan project. That said in the Fukanzazengi he tips his hat to the koan way, informing us how “enlightenment brought on by the opportunity provided by a finger, a banner, a needle, or a mallet, the realization effected by the aid of a fly whisk, a fist, a staff, or a shout, cannot be fully comprehended by human discrimination.” He gets engaging koans as a leap beyond the traps of form and emptiness. Of that there can be no doubt.

But, instead of those many koan as we who’ve inherited Hakuin’s way practice, Dogen points us to one. First he tells us, “The practice of Zen has nothing whatever to do with the four bodily attitudes of moving, standing, sitting, or lying down.” So, it isn’t simply a matter of assuming a correct posture. Rather he is inviting us elsewhere. Then he tells us where. “The zazen I speak of is not learning meditation. It is simply the Dharma-gate of repose and bliss. It is the practice-realization of totally culminated enlightenment. It is things as they are in suchness.”

It is, in my words, the mind of presence manifest.

This is what he calls practice-enlightenment. In fact, I’ve seen that term rendered without the hyphen, simply reading practiceenlightenment. One word. One thing. In some ways it is taking up the koan of just sitting as if it were a huatou, the single koan one needs for a lifetime of engagement.

What I am sure of is this. You want a classic koan? Show me practiceenlightenment. Show me the mind of presence manifest.

Here we’re invited into something beyond a mere quietism. And, of course, that’s the shadow of the way of just sitting. People “proof text” the term and warn against “gaining mind” with unfortunate consequences. We are not being invited into being bumps on some log. Although, sadly, I’ve seen people think that is precisely what shikantaza is.

I offer an alternative understanding. With shikantaza we’re given a place to put our great questions, our deep curiosity, our profound longing. With shikantaza we have a place to bring our hurts and wounds. Here we’re being invited into a mysterious alchemy of the heart. So. Yes, gaining mind does not carry us across the river. And it is no different than our awakening.

And for this just one more term. Bodhicitta. It’s a Sanskrit term central to the Mahayana, our great way. It is the mind turned to awakening, to wisdom and compassion. The mystery of bodhicitta, our desire for awakening is discovered as we experience it, and as we surrender it.

But this isn’t surrender in the sense of burying it or throwing it away. Rather it is a transformation into confidence, or trust, or maybe the right word is faith. In Japanese Shinjin, the mind of the Buddha. Here we discover faith as a matter of heart, as an invitation into an ancient love. Master Taizan Maezumi tells us,

“When you do shikantaza, have faith in the fact that your zazen is the same zazen as the zazen of the Buddhas and (Ancestors). Have this kind of faith. Then, just sit. Since your zazen is the same zazen as that of the Buddhas, you don’t need to worry about anything: just sit. Appreciate that your zazen is the zazen of the Buddha. The zazen of Shakyamuni Buddha is okay; the zazen of the Buddhas and (Ancestors) is okay. In other words, you are not sitting; Buddha is sitting.”

If we bring our full selves to the matter, we find something breaks open. Well, sometimes breaks open. Sometimes unfolds like a flower. Our images both liberate and trap. We must walk carefully. Gently. And fiercely at the same time. And so Dogen charges us to “Devote your energy to a Way that points directly to suchness.” And critically he tells us how. “If you concentrate your effort single-mindedly, you are thereby negotiating the Way with your practice-realization undefiled. As you proceed along the Way, you will attain a state of everydayness.”

So, if it’s a koan how do we engage shikantaza? How do we meet everydayness?

Dosho Port, a contemporary Western Zen master tells us about his introduction to shikantaza and his introduction to koan introspection. “Katagiri Roshi’s initial instruction was to become one with the breath and Tangen Roshi advised me to begin muji (the Mu koan) by becoming one with Mu.” Within our discovery of oneness with all things the mystery is revealed, all gates are opened.

Just be present. The mind of presence. The mind of presence manfiest.

A koan is an assertion about reality and an invitation to intimacy. What does practice-enligthentment mean? What is nonthinking? Here the koan is to sit down and become Buddha. The state of everydayness. The koan way. The great Zen way.

Just this.