For those among my friends who do not know, I am working on my next book, a study of Zen meditation with a focus on koan introspection.

The following was deemed by my editor as not precisely on point for the book. Like much of what I write, apparently.

However, thanks to my having a blog you can determine for yourself whether it has some merit on its own. I have added in a few things, and expanded on a point or two, hoping for clarity as a posting. And with that, here you are, some odds and ends on the formation of Zen teachers…

Originally the place of formation for a teacher was the monastery, the traditional lair of Zen dragons. Vinaya-ordained monastics have been the normative carriers of the Dharma throughout the Buddhist world (the Vinaya is the monastic code that evolved out of the Buddha’s original community). And with the exception of Japan it is the normative form of regular practice and of religious leadership in most of the Buddhist world.

Some form of monastic practice has been the container for Zen meditation throughout all of its history. Usually as with the Vinaya model the monastic commitment has been for a lifetime, although there have been numerous instances of individuals who spent periods of time in the monastery and then returned to a lay life.

However, in Korea and Japan, systems of “married monks” have also emerged. In Korea, the vast majority of Buddhist clerics continue to be celibate. But, tiny Taego Order offers a training model that produces clerics that are more akin to ministers or priests than monks. There they continue to profess the Vinaya vows but reinterpret the rules regarding celibacy as constancy within one’s committed married life.

In Japan, however, a model of married clergy has become the principal form of religious leadership. Being aware of this shift in ordination patterns is critical for understanding the Zen transmission in the West. Japanese Zen was the first and continues to be the leading stream of Zen practice among Westerners.

The evolution of Japanese bodhisattva ordination, the unique ordination model in Japan, is a story of fits and starts, of politics and spiritual innovation. It is also a story marked by confusion, conflict, and occasionally self-deception. It is also the story of a remarkable ordination model, one that might be best adapted for carrying the Dharma forward into Western culture. For an overview of how this came to be, I recommend Richard Jaffe’s study of the Soto and Shin schools, Neither Monk nor Layman: Clerical Marriage in Modern Japanese Buddhism.

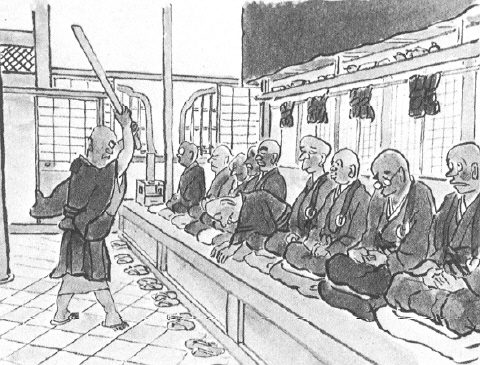

It is important to note that our Western-style, Japanese-derived Zen monastic training is different than what one experiences in Japan. While my own experience has been entirely in this country, I have a good number of friends who’ve trained in Japanese Zen monasteries. The word “brutal” is commonly used when they describe that experience. The system has on occasion been derided as a British boy’s school made really hard. Frankly, this style of training is probably not transferrable to the West, although there are some pretty good approximations.

The American-born Zen priest Koun Franz, who spent substantial time in a Japanese Soto Zen monastery, describes his part of his experience there as simply being a “sock puppet.” He elaborates on that startling image. The practice becomes “a container in which the only real choice you make is to stay or to go; the rest are made for you.” He adds, “There’s a selflessness, a letting go there that’s very powerful.” This letting go is at the heart of all of Zen’s disciplines when fully engaged. Franz underscores how it really wasn’t about control at all, “Your actions are prescribed because your physical expression is considered to be the voice of the Dharma itself, so you’re learning that embodiment as your central curriculum.”

Our Western-style adaptation of Japanese monasticism is both similar and quite different. The most obvious connection is that strong emphasis on seated Zen meditation, hours every day, and many more during meditation retreats. Otherwise, Western Zen monastic training looks a bit more like Western Christian monasticism. It can be quite strict, there are many, many rules to observe, but the application is nowhere near the tightest container one encounters in Japan.

My own monastic experience here in the West was powerful and transformative. It forced me to look at my patterns of behavior, what I considered important, and even who I was. As the container for my meditation practice, it made everything about my Zen training more immediate and urgent. Anyone who can find the time, whether they’re on a teacher-training track or simply digging deeply into the Great Matter, I think the experience is enormously valuable. And I recommend it.

Increasingly we also have ordained and non-ordained Zen teachers who have trained without the formal monastic experience. That training is usually contained within ninety or hundred-day retreats. That retreat model traces back throughout Buddhism’s history, finding its origins in the rainy season retreat during the Buddha’s lifetime.

But the most important part has been meditation itself. And its intensive application. I served on the membership committee for the American Zen Teachers Association for a decade. They are a group that desperately does not want to be a credentialing body. But wanting to be a support group, they do want to limit membership to people who are actually occupying the space of Zen teacher.

Casting about for some external markers of that status, one thing that we who were charged with admission to membership noticed was that the people on the inside of that club pretty much all had sat extensively before being authorized to teach. So, we began to look at what that meant in a quantifiable way.

The minimum among these teachers, not the average, the minimum was about a year of hard pillow time – that is a year of days in retreat with about nine, ten, or eleven hours on the pillow. Surveying the teachers in my own community, Boundless Way, the average was more in the neighborhood of two years.

There were other requirements that the teachers in the AZTA also met. And that’s critical to note. For instance, using Boundless Way as a marker, we usually also require completion of koan introspection practice for full authorization. More on that in a moment.

Whatever. That objective element of a boatload of meditation supervised by people who’ve done this discipline themselves for a boatload of time makes sense in a tradition that’s all about a meditation discipline and guiding people through the interior experiences one encounters within that discipline. So, that seems a constant among teachers of Zen in the West, at least in its normative forms. There are, sadly, also people who have titles, but marginal preparation for taking on the tasks of leadership.

And then there is the matter of koan practice.

For various reasons the Rinzai school has not taken significant root in North America. Both of the principal teachers to take up residence in North America became embroiled in bitter scandals. However, some of their successors are beginning to establish stable communities. And now there is a steady current of visiting Rinzai masters, Master Shodo Harada perhaps the most notable among them.

However, it’s the Harada-Yasutani koan way that has mainly opened the door of a new training model for Westerners. It is a reformed koan curriculum created by the Soto master Sogaku Daiun Harada at the turn of the last century. And its major forms slightly modified by one of his successors, Hakuun Yasutani. As it relates to teacher formation in the West this koan curriculum replaced the monastery as that tight container.

Using the koan curriculum together with shorter intensive retreats of one, three, five, and seven days can be seen in Sanbo Zen, the Diamond Sangha, and the Pacific Zen Institute’s lay lineages. It also becomes a principal training model for the White Plum lineage, following Maezumi Roshi’s training with Yasutani (and a lay Rinzai master, Koryu Roshi). And this includes our own Boundless Way Zen and those closely related communities like the Nebraska Zen Center, the Great Heartland Buddhist Temple of Toledo, the Empty Sky Zen Sangha, and the Sacramento Zen Center, all of which combine traditional Soto lineages with koan introspection.

In addition to the Japanese lineages, there are other schools of Zen presenting in the West. Teachers from China, Korea, and Vietnam have established communities and lineages here. I attempt to sort through some of the history’s thicket in my Zen Master Who?: A Guide to the People and Stories of Zen.

Most have not established substantial followings in the West. There are, however, two substantial communities in the West that do not derive from Japan.

One of these was founded by the Vietnamese monk, Thich Nhat Hanh. However, the Order of Interbeing does not emphasize either shikantaza/silent illumination, nor koan introspection. It offers instead a system called the fourteen mindfulness trainings. There are definitely aspects of the community and the trainings that would be recognized within other Zen communities, and Thich Nhat Hanh himself is widely and justly respected. But there are sufficient enough differences from other Zen traditions of practice that the Order falls beyond the focus of this reflection. It is in many ways a new Buddhist community following its own trajectory.

The other non-Japanese derived community is the Kwan Um School of Zen established by the Korean monk Seung Sahn. After Thich Nhat Hanh’s Order of Interbeing, the Kwan Um School is probably the next largest. Its size and reach into the Western world is rivaled only by the Suzuki and Maezumi lineages. And it has its own penumbra of teachers who have left the Kwan Um school and lead independent communities. The most significant is probably the Golden Wind Zen Order established by the American successor to Master Seung Sahn, Master Robert Jibong Moore.

While the Kwan Um School has monastic practitioners, the leadership is majority lay. The training of these lay teachers usually includes a significant monastic training period, similar to the western-style, Japanese-derived training. And it includes a koan formation system. Any consideration of Zen teacher formation in the West, needs to include this dynamic community in its reflections.