They prayed to the good gods for a child. But without success. Finally, they turned to the Awakened one. They offered incense and flowers and prayed for a child. They made donations to the support of the Awakened One’s community. Not long after, one morning at breakfast, they saw the inside of their house gradually grow light. It continued ever brighter, until it was impossible to see for the shining brightness. Strangely they were not afraid. Then, as suddenly as it arose, light passed away. And everything was normal again.

Not long after the woman knew she was pregnant. The couple decided when the child came, they would name it, boy or girl, Light. Nine months later their son, Light was born.

Light was an unusual child. He seemed completely uninterested in worldly matters. Instead he would wander into the nearby forest and climb up the mountain. He read the sacred texts of the intimate way and began to compose poetry.

When he came of age, he decided to formally inter the intimate way as a monastic. He went to Fragrant Mountain and entered the Dragon Gate monastery. There his hair was cut, and he took his vows. Light began by studying the sacred texts both those of the Elders and those of the Great Way. In time his renown as a scholar began to spread. But he knew something was missing. There continued to be a wound in his heart. Some sense things were wrong that no matter what he did, he could not shake off. He began to wander among the temples and monasteries speaking with various masters. And he spent increasing amounts of time alone in the mountains.

After several years of wandering, at the age of thirty-two he returned to Fragrant Mountain. There while deep in meditation a spirit appeared before him. It looked like an old nun, but he wasn’t sure. He could see her and right through her a the same time. She smiled gently at him, he could see the wall behind her smile, and said, “This is not where you will open your heart. Go south, my child.”

The spirit reminded him of his mother. Something about how its hair curled. Or, maybe it was that smile. At the same time Light was sure it was not her. Still. He felt the words were true. He told the master of Dragon Gate about his vision. The old monastic listened to the story, then ran her hand gently across Light’s shaved head, touching the seven unusal bumps that ran from his forehead and back. They reminded her of mountain peaks.

She said, “Go south, dear one. Head for the monastery of the Wooded Mountain. There you’ll find the master Bodhidharma. He will open your heart for you.”

The next day Light packed up what little he owned, a second robe, a thin blanket, a toothbrush, a razor, his bowls, and three books, and began to walk south. It was a hard journey. Things happened. At one encounter he thought he might die. But, he continued, and finally he arrived. At the monastery of the Wooded Mountain.

There Light was introduced to the master, who set him to the practices of intimacy. Light learned to sit quietly, present, noticing. He began his practice in earnest, sitting with a burning heart, seeking the secrets of the great matter. But instead of seeking trough books, or seeking by wandering in nature, he simply watched the currents of his mind. Light met regularly with his teacher. But, even with all this he couldn’t see through.

One day it all felt too much. His whole life seemed a waste. Desperate, he went to his master’s hut. But the door was closed. He knocked, but there was no answer. He felt a wave of panic. Of desperation. He knocked again, harder. And still there was no answer.

Not knowing what else to do. Not having any sense of somewhere else to go, he pounded and kicked the doorjamb. “Master!” Master!”

Finally the old teacher opened the door. “Yes?”

Light didn’t realize until that moment he was holding his razor. With a flash of the blade he cut his arm and bleeding, presented it to the teacher. “Please, please. My mind is afire. Please set my anxiety to rest.”

Watching his disciple holding his arm to staunch the bleeding while listening desperately for a turning word, Bodhidharma said to Light, “Bring me your mind, and I will set it to rest.”

Light wailed. “I have searched. Deeply. Broadly. With all my heart. But I cannot find any place where there is some thing I can actually call my mind. It is just thoughts and feelings arising and passing away. I find no one thing.”

Bodhidharma sighed. “Yes. Yes. That’s it. Knowing that, your mind is at rest.”

In the moment, Light understood.

The Case

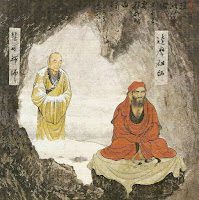

Bodhidarma sat facing the wall.

The second patriarch [Shenguang, later called Huike], standing in the snow, cut off his arm and said, “Your disciple’s mind is not yet at peace. I beg you, Master, give it rest.”

Bodhidharma said, “Bring your mind to me; I will put it to rest.”

The patriarch said, “I have searched for the mind but have never been able to find it.”

Bodhidharma said, “I have finished putting it to rest for you.

Wumen’s Verse

Coming from the West and pointing directly to it –

All the trouble comes from the transmission;

The one who disturbs the monasteries

Is originally you.

The silent master was cautious enough to try the sincerity of the newcomer before admitting him. Shenguang was not allowed to enter the temple, and had to stand in the courtyard, deep with snow. His firm resolution and earnest wish kept him standing continually in one spot until dawn, beads of frozen teardrops on his breast. At last, with a sharp knife he cut off his left arm and presented it, showing his resolution to follow the master even at the risk of his life. Thereupon, Bodhidharma admitted him into the order as a disciple, fully qualified to be instructed in the teaching of Zen. A new name was given to the disciple by the master. It was Huike, which is pronounced Eka by the Japanese. Bodhidharma had a few other disciples, but Huike was the one who received the bowl and the robe from him, becoming the second patriarch of Chinese Zen.

The moment we think we have taken hold of a thought, it is no more with us. So with the idea of a soul, or an ego, or a being, or a person, there is no such particular entity objectively to be so distinguished, and which remains as such eternally separated from the subject who so thinks. This ungraspability of a mind or thought, which is tantamount to saying that there is no soul-substance as a solitary, unrelated ‘thing’ in the recesses of consciousness, is one of the basic doctrines of Buddhism. Huike was brave enough to cut of his left arm, but he did not have the nerve to use the knife upon his own mind and thought. Bodhidharma was like a good surgeon, who uses his knife as quick as a flash. The operation was finished before the nurse could give any anesthetic to the patient. Who was sick? What was the trouble? It was merely illusory; unreal. Your mind is already pacified.

Wumen’s Commentary

The broken-toothed old barbarian came thousands of miles across the sea with an active spirit.

It can rightly be said that he raised waves where there was no wind.

In later life he obtained one disciple, but even he was crippled in his six senses.

Ha! The fools do not even know four characters.

“My mind has no peace.” Only when he has emptied himself has he peace of mind.

“I beg you.” There is no point in begging for one’s peace of mind, but one cannot help doing it all the same.

“Please pacify my mind.” You cannot pacify your mind while you are asking others to do it for you.

“Bring your mind here.” You cannot find your mind, much less bring it forth.

“I will pacify it for you.” Peace of mind is spontaneously brought about.

“I have searched for my mind.” Human beings have long searched for the mind.

“I cannot take hold of it.” You can take hold of it, but not in the way you expected.

“Now your mind is pacified.” Your mind is pacified spontaneously, not by others.

An old Zen Master sang: “For years I suffered in snow and frost; / Now I am startled at pussy willows falling.” Not only Zen, but any religion in the world must have the reason for its existence in the guidance it gives to those who pursue this quest for peace of mind. By making this search one may finally be led to the realization that every effort is in vain. True peace of mind, however, can be obtained only when one is personally awakened to the stark-naked fact that every effort is ultimately in vain. Seek, struggle, and despair! “I have searched for the mind, and it is finally unattainable” — this reply comes from the experience of plunging into another dimension. It is the cry of the person who has experienced that “the whole universe has collapsed and the iron mountain has crumbled.” The key to the koan is in the experience of grasping the live significance of this word “finally” as one’s own.

Anonymous Zen Master’s Commentary (quoted by Shibayama)

Whenever it may be, wherever you may be, your mind is at peace, because there is no mind outside your body; because there is no body outside your mind. Since your body and mind have already dropped away, what is there to be pacified or not pacified? How wonderful is this mind that is always just at peace!

Another Anonymous Zen Master’s Commentary(quoted by Shibayama)

To try to find a man on an uninhabited island may prove fruitless. Once, however, it is definitely established that there is no man there, the island comes into the discoverer’s possession. This is international law. It is the universal law effective through the ages. The whole universe now comes into his possession!

We are all searching for truth and peace of mind outside ourselves, which is like hunting for a man on an uninhabited island. Once you have found out that the island is uninhabited, your desire to search for a man there will end. When you stop desiring, your mind will come to rest. There will be no problems, no discontent, no frustrations, no uneasiness. You will be at peace, just as you are. Is there any happiness other than this?

The anguish of Huike facing Bodhidharma is the anguish of the heroes and heroines of fairy stories and folktales who must strive constantly, practicing that which cannot be practiced, bearing the unbearable. This is a treasure of the Path disguised as sheer misery. This treasure is found in all religions worthy of the name. It is the “dark night of the soul.” Huike had no choice but to enter this dark night. We have no choice either. Bodhidharma said, “There, I have completely put it to rest for you.” The rest that Bodhidharma confirmed in the heart-mind of his disciple is the same rest he sought to confirm in the heart-mind of Emperor Wu with his words, “I don’t know.”

If you ask someone who is on the Way, “Why are you practicing?” the answer you may well hear is, “I don’t know, I simply have to go on,” or some variation of this. Indeed, one could say if a person does know, he or shie is not very far on the Way. If one persists despite the travail, at a certain stage in the practice the frustrations, conflicts, and defects suffered by the personality become the fuel driving the practice forward. It is during this time that, in spite of oneself, one can make immense efforts that in sober moments seem impossible. You will never find it if you look for it; but if you do not look for it, what hope do you have?

Anonymous Verse

The snow of Shaolin is stained crimson;

let me dye my heart with it

as humble as it may be.

Fenyang’s Verse

Nine years the founder faced a wall, awaiting the proper potential;

Standing in snow up to his waist,the successor never relaxed his brow;

Respectfully he asked for a method to pacify the mind:

Searching for the mind and not finding it, for the first time in his life he was free from doubt.

Foguo Bai’s Verse

Thinking, why seek to pacify mind?

Seeking out peace of mind causes pain to the body.

Three feet deep the snow where he once stood:

Who knows who it is in the snow?

Hotetsu’s Verse

No one’s arm was lost,

No weapons, no defenses, cut through;

Thus peace and disarming mutually entail —

And both are always already established.