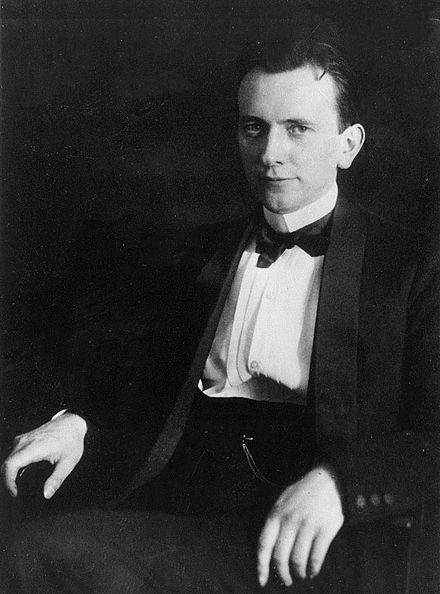

Karl Jaspers

and the Path of the Spiritual if not Religious

Karl Theodor Jaspers was born on this day, the 23rd of February, 1883, Oldenburg, in Lower Saxony, in Germany.

He began studying law but changed to medicine, taking his doctorate in 1908. Two years later he married Gertrud Mayer. Three years after his marriage Jaspers began teaching psychology at the University of Heidelberg. By 1921 he had completely shifted his focus to philosophy. The university accommodated him, shifting his position to philosophy.

When the Nazis came to power, because his wife was Jewish Jaspers was forced to retire from teaching. In 1938 he was prohibited from publishing. Thanks to his prominence as well as the protection of their friends who stood by him, despite a continuous threat of deportation to a concentration camp, the couple were able to survive until liberation. In 1948 the Jaspers family moved to Switzerland, where they would remain for the rest of their lives.

Jaspers made major contributions to both psychiatry and philosophy. But, my interest in him turns on his theological reflections.

He coined the term axial age for that period when the majority of the world’s religions came into being. Karen Armstrong would further develop this concept in her wonderful reflection the Great Transformation.

Jaspers was singularly unimpressed with Rudolf Bultmann’s quest to demythologize Christianity. Instead he steeped himself in the great mystics of the West, as well as the philosophers Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, and very much Kierkegaard and his great “leap.” At some point Jaspers turned his attention to Eastern religions, particularly Buddhism.

Me, I find in this blending a forerunner of a modern philosophy of religion, and something quite compelling.

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Jaspers’ “approach to religion is one of extreme liberalism and latitudinarianism, which dismisses the claim that transcendence is exclusively or even predominantly disclosed by religion. The truth of religion, he intimated, only becomes true if it is interpreted as a human truth, not as a truth originally external or prior to humanity.”

And, so, he also offers a critique. “In its orthodox form, however, religion normally prevents the knowledge of transcendence which it purports to offer.” I wouldn’t call him the original spiritual but not religious. But, he brought a deep sympathy with the project of the religious quest, while clearly skeptical of any particular religion’s claims to own that quest or the winning of that quest.

While he didn’t like the term applied to him, Jaspers is broadly considered an Existentialist. I found his broad humanism, his rejection of any kind of essences in things, and his locus of experience in our lived lives very helpful in my own understanding both of Buddhism and my spiritual longings.

Me, I found Karl Jaspers a compelling thinker. And he is someone who, in the great proof of the pudding, made right choices in hard times. Or, at least, if he didn’t actively resist the evil around him, he didn’t bend his thinking and life to the totalitarians when they came. This has not been true of every philosopher or religious leader. (And, yes, I am thinking of you, Martin!).

As a thinker and person he has helped me in putting some of my larger view together.

So, I remain eternally grateful to that old German.

Happy birthday, Karl! May you long be remembered…