The Dawn of Nichiren Buddhism

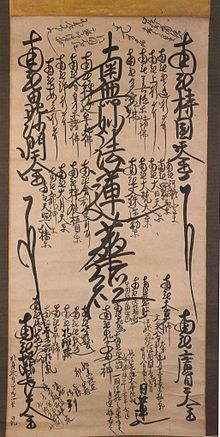

Namu Myoho Renge Kyo

On the 28th day of the fourth lunar month, that would be today, the 28th of April by our reckoning, in the year 1253, the Japanese Tendai Buddhist monk Nichiren Shonin, proclaimed that the Lotus Sutra was the epitome of all Buddhist teachings.

And with that, simply calling upon the title of the Sutra can bring about liberation.

南無妙法蓮華経

Namu Myoho Renge Kyo

Which can be translated variously as “I take refuge in the Lotus Sutra” or “Homage to the Lotus Sutra” or “Devotion to the Mystic Law of the Lotus Sutra” or “Glory to the Dharma of the Lotus Sutra.”

The mantra is called the Daimoku or O-daimoku.

There was a goodly run up to this event.

Nichiren was born on the 16th of February, 1222, in what is today Chiba Prefecture in Japan. He became a monastic at eleven, and was ordained priest at fifteen (or sixteen, I’ve seen both dates). He spent years in study. Eventually being drawn to the power of the Lotus Sutra. And coming to the belief that simply heartfully calling out one’s devotion, as with the mantra, was in itself, by itself the healing of the broken heart. A formula perfectly fitting our age.

This age. In Buddhist tellings of the way things are, everything dies, everything passes away. But, in great cycles of birth and maturity and dying. Followed by another cycle. The end part of that cycle is called mofa in Chinese and mappo in Japanese. And in East Asian Buddhism while various periods have been considered the dawning of the mappo era, in popular Japanese Buddhism, through a calculation of when they thought Gautama Siddhartha lived, and giving each of the three eras, the beginning, the middle, and that end a thousand years each, set the year 1052 as the dawn of mappo. (Which for the calendar minded puts us at the end of the end times.)

Hard times. Impossible times. Our times. Times where our own power fails. And so times calling for intervention. Like this petition to heaven, this call on the Sutra itself, and its salvific powers.

For this project Nichiren drew upon the work of earlier Tendai monks, especially the ninth century Japanese Tendai founder Saicho and the tenth century scholar monk Genshin. Each offered variations on the mantra as expressions of gratitude for the Sutra. But it was Nichiren’s version that worked, at least for many people.

And his teachings of this simple practice did touch many hearts.

Nichiren himself was a vociferous polemicist. He attacked the other schools of Buddhism, and was the subject of denunciations. He was banished from Kamakura twice, condemned to execution, and eventually exiled for years. His followers were subject to persecution. In these years of persecution he began to see himself as an incarnation of the Bodhisattva Visistacaritra.

In 1274 he was pardoned, and returned to Kamakura from exile. However, not long after he retired to Mount Minobu, where he stayed for the rest of his life. There he engaged in extensive correspondence. In 1282, after designating six of his disciples successors in teaching, he died.

Nichiren Shonin was a prolific writer offering a powerful and concise practice for hard times. Like his rough contemporaries Eihei Dogen and Shinran Shonin, he focused a significant part of his teachings to the householder community and in particular noting the equality of women in the dharma. Historians identify 162 immediate disciples of the master, 47 of them were women. Nichiren emphasized the saving possibilities of the practice for all people, men and women, clerical and lay. Apparently the vast majority of his correspondence is pastoral, kind, and sensitive. In strong contrast to the institutional polemics for which is better known.

While most people in the West who encounter Nichiren Buddhism through Soka Gakkai, which has mounted an aggressive evangelizing mission that has both put many people off while inviting many others, it is also possible to have first heard the mantra at peace demonstrations led by members of the Nihonzan Myohoji.

There are several organizations that continue his teachings. The largest are the clerical Nichiren Shu and Nichiren Shoshu, and the lay organizations Risho Kosei Kai and Soka Gakkai.

While SGI has been justifiably criticized for its aggressive evangelizing in the past, as well as early mission emphasizing material gains from the practice, it is also the only Buddhist school to have met and encouraged people outside the normative “convert” profile of the highly educated white population with notable success. It has a lot of poorer and working class members, as well as a large percentage of people of color, especially African American.

I’ve also encountered a fair number of unaligned practitioners. For more on the many branches of the school, Wikipedia offers a good overview.

Here’s a lovely video of a talk by Myokei Caine-Barrett, bishop of the Nichiren Shu in North America. I think of her presentation as sort of where the rubber hits the road. An example of how the practice can seep into a life…

A nice little pitch for the practice.

Basic instruction.

And then putting it together…