GOD IS ONE

Francis David, Reformation Unitarianism & Some of Its Significance for Contemporary Unitarian Universalists

A Sermon

27 January 2013

James Ishmael Ford

First Unitarian Church

Providence, Rhode Island

Text

In this world there have always been many opinions about faith and salvation. You need not think alike to love alike. There must be knowledge in faith also. Sanctified reason is the lantern of faith. Religious reform can never be all at once, but gradually step by step. If they offer something better, I will gladly learn. The most important spiritual function is conscience, the source of all spiritual joy and happiness. Conscience will not be quieted by anything less than truth and justice. We must accept God’s truth in this lifetime. Salvation must be accomplished here on earth. God is indivisible. Egy Az Isten. God is one.

Francis David (arranged by Richard Fewkes)

John Gibbons, our UU minister in Bedford, Massachusetts tells an anecdote. It was 1994. Intrigued by stories they’d heard, and even though few could even find Transylvania on a map, the Bedford congregation decided to sign up for our denomination’s new partner church project. They promptly found themselves teamed up with a congregation in a tiny village somewhere on the outskirts of nowhere at one of the edges of Transylvania. They decided to send a delegation including John to see what they’d gotten themselves into. Arrangements were made, transportation was put together and they took off.

Days later, as the two Volkswagen buses carrying them made their way out to that edge of nowhere, perhaps a mile or so from the village they were stopped by a band young men on horseback and young women in horse-drawn carts, all dressed in traditional garb for the occasion. One of the young people then read from a proclamation in which the villagers declared this visit was as important to them as when the magi made their way to Bethlehem.

All of a sudden John tells us he felt woefully underdressed.

In his tellings of this adventure and all that has followed, John describes something happening that was life transforming, offering both a picture of a different kind of Unitarianism than we know, and an invitation to take our own liberal faith more seriously and, possibly, even, in new and deeper directions.

Our English speaking traditions are firmly rooted in the Enlightenment. But there are antecedents worth noting. For instance we owe much to the naturalistic inclined Unitarianism of the Reformation era Polish Brotherhood, perhaps better known as the Socinians. Certainly bits and pieces of their publications can be found in the libraries of John Locke and Isaac Newton and others of our Enlightenment forbearers. One of the early English translations of the Racovian Catechism, perhaps the most important document published by the Socianians, is usually attributed to the intellectual founder of English-speaking Unitarianism, John Biddle.

However, it appears that until the nineteenth century we English speaking Unitarians were pretty much innocent of our other cousins, the Unitarians who today are found in Hungary and Romanian Transylvania. Oh, an English traveler published an account of these Unitarians in Transylvania in the early seventeenth century. And later in the middle of that century, a Hungarian Unitarian who would later become one of their bishops visited England, creating something of a stir.

But that’s pretty much it, until Sandor (or, Alexander) Farkas visited England and America at the beginning of the Eighteen thirties. His essay, an “Account of the Unitarians of Transylvania” was published in 1832. From that time English-speaking Unitarians were fascinated with these our older cousins, people who had suffered persecution, sometimes-terrible persecution, and often tottered at the edge of extinction, but unlike the Polish Unitarians who were wiped out, survived, and survive to this day.

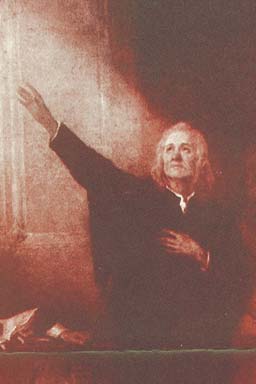

Together with learning of Transylvanian Unitarians we have discovered one of the most compelling spiritual figures, frankly, of world religion. Here we are presented with a fierce intellect and questing spirit, a religious leader and social rebel, with in my opinion more substance, certainly more intellectual and spiritual rigor than either Calvin or Luther, or, any of the rest of that Reformation gang. We have found, thanks to these connections with Hungarian speaking Unitarians not just a distant cousin, of whom we can be proud, but an exemplar, a pointer of the way, a teacher and guide on our own way: we have discovered Francis David. And with him, we get a cast of characters and a story that more truly than most, is our story.

Francis David was born at the beginning of the sixteenth century in Kolozavar, today Cluj, in the kingdom or principality of Transylvania. Kingdom from the perspective of the Transylvanians themselves, principality in fact as they were within the thrall of the Ottoman Empire. His father was a shoemaker, but his mother came from Hungarian nobility, so he had social access. His intellectual capacities were recognized early on and patrons supported his education, even sending him to Wittenberg for four years for advanced studies, after which he was ordained a Catholic priest. Spiritually restless, and intellectually rigorous, he chaffed at the strictures of the Catholic faith, eventually converting to Lutheranism. He quickly was elected the Lutheran bishop for Transylvania. Under the influence of George Biandrata, physician to the king and a significant spiritual intellect in his own right, David continued to wrestle with his faith and eventually declared for the more rationalist Calvinism, then quickly becoming the Calvinist bishop of Transylvania.

The evolution of his faith continued. He and Dr Biandrata found themselves deeply influenced by the Spanish anti-Trinitarian Michael Servetus and the great Dutch humanist philosopher Erasmus. Among the problems for David was the lack of any scriptural clarity around the nature of the Holy Spirit, and with that the whole idea of God being described as a trinity.

In the meantime Dr Biandrata arranged for his friend to be appointed court preacher. His command of the scriptures, his eloquence both in pulpit and in debate, and with his ability to speak with equal eloquence in Hungarian, German and Latin, it appears no one was able to meet him head to head in disputation. And significantly, gradually, actually not that gradually, Francis David’s preaching and eloquence became more and more obviously anti-Trinitarian.

These questions and disputes gradually spread beyond the court. It may be hard in our time and place to understand how powerful and compelling these questions were. Or, the physical danger that accompanied questioning such bedrock assumptions – an area that neither Luther nor Calvin ever dared go. Of course David knew this was dangerous territory. As did Biandrata, naturally more cautious than his friend, who exercised his influence to keep David from fully and publicly expressing the flood of doubts touching on all manner of ecclesial matters that his studies brought forth. For at time.

Not that the central question about the nature of God wasn’t being discussed. In fact the disputes among Hungarian speaking theologians eventually became formal debates and even synods, and these would rivet the public’s attention, as well as the court, and the king. David and Biandrata published a catechism, and David published a book, “On the True and False Knowledge of the One God,” which clearly laid out a Unitarian theology. David dedicated the book to the king, writing, “There is no greater piece of folly than to try to exercise power over conscience and soul, both of which are subject only to their creator.” I find it interesting we won’t hear the likes of this again until Roger Williams.

Here we come to the third of the great personalities who would birth the first church in the world that named itself Unitarian. John Sigismund ruled the “Eastern Hungarian Kingdom,” what we call Transylvania, he was also subject within the swirling political scene to the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Great. I suspect the surprising religious tolerance of the Ottomans may have had some influence on the king. What we do know, is that however many the tributaries that flowed into the king’s heart, two things came out of that deep place.

First, in 1568, the king promulgated an edict of tolerance, the first proclamation of religious freedom anywhere in Europe. In his proclamation the king declared, “Preachers shall be allowed to preach the Gospel everywhere, each according to his own understanding of it. If the community wish to accept such preaching, well and good; if not, they shall not be compelled, but shall be allowed to keep the preachers they prefer. No one shall be made to suffer on account of his religion, since faith is the gift of God.” Here, we find the echoes of his court preacher’s dedication in his book. While not complete freedom, that was limited to Catholics, Lutherans, Calvinists, and Unitarians, it did extended official tolerance to Orthodox Christians, Jews, and Muslims.

It was a significant, an enormously significant act. In the rest of Europe at this time blood was flowing freely over religious disputes, Catholics killing Protestants, and Protestants killing Catholics as well as other Protestants, and everybody killing Jews. In Transylvania something else was happening.

And, second, and in my heart completely connected to that declaration, King John Sigismund embraced the new Unitarian faith preached by Francis David. With the king’s patronage and the institutional insights of Dr Biandrata, Francis David, for the third time in his life was elected a bishop, this time for the new Unitarian church.

For a handful of years something wonderful flourished in Transylvania. But then in 1571, under clouded circumstances the king died. His successor was a Catholic, and almost immediately persecutions began. This led to a bitter division between Dr Biandrata and the bishop. Meanwhile David’s thinking continued to advance, following the dictates of his scholarship, his spiritual insight, and his conscience. Dr Biandrata warned his colleague now was not the time to proclaim his ever more radical positions, they needed to protect their new church. But the bishop refused to be silent.

Finally the doctor, fearing for the fragile church, joined those who denounced the bishop, and he was quickly tried and convicted of heresy. He was thrown into prison, where not long after, he died. The church barely survived the persecutions, which would in fact prove simply to be the first of many persecutions over the ensuing years. But, it survives.

And, today, we have come into contact with that church.

And what do we see? Here I think of John Gibbon’s comment about that proclamation of the significance of the encounter. Like the magi visiting the holy family. Of course, who is who in this is not at all that clear. But, there is a star. There are visitors. And there is something holy and precious being discovered.

From one perspective a rich and intellectually inclined religious community stumbles upon a persecuted church that survives with dignity, if in poverty in the face of continued opposition, sustained by a heart-full faith. From another perspective we have two cousin traditions, each holding up a mirror for the other. They, showing what a simple reformation of the heart, focusing on a God that is an overwhelming love, can reveal, while we following all the questions their founder asked right down to the bottom, discovering the power of intellectual honesty, even in religion.

For me, what I see is the complementarity of heart and mind, of love and wisdom. And in that, a pointing of a way forward for us, here, today. Our way is about an unrelenting questioning of authority, and, while we sometimes forget, it is ever as much about constantly opening our hearts wider and wider.

For me this meeting is that joining of heart and mind, of love and wisdom.

This can be, if we are careful, a call to our own reclamation of a whole faith, the way of the wise heart, the path of our teacher, the remarkable Francis David.

Amen.