THE OLD WOMAN BURNS DOWN THE HUT

A Dharma Talk

James Myoun Ford

7 March 2014

Boundless Way Temple

Worcester, Massachusetts

The Case

An Old Woman Burns Down a Hermitage

Entangling Vines: A Classic Collection of Zen Koans

Case one hundred, fifty-four

Translated by Thomas Yuho Kirchner

There was an old woman who supported a hermit. For twenty years she always had a girl, sixteen or seventeen years old, take the hermit his food and wait on him.

One day she told the girl to give the monk a close hug and ask, “What do you feel just now?”

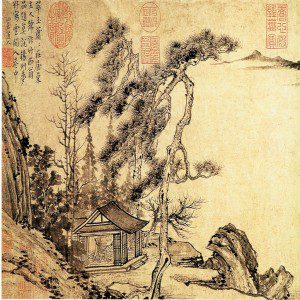

The hermit responded,

An old tree on a cold cliff;

Midwinter – no warmth.

The girl went back and told this to the old woman. The woman said, “For twenty years I’ve supported this vulgar good-for-nothing!” So saying, she threw the monk out and burned down the hermitage.

I first ran across this story, I’m pretty sure, in Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. Maybe I was seventeen. I recall how I was both shocked and fascinated by it. Sex in a spiritual story didn’t get any better for me. And not going to the way my Baptist upbringing inclined me to assume it would go was a clear bonus, even as I didn’t really get where it was going. Where was the simple and clear moral? Why drive the monk out for not responding to the girl? Why burn the hut to the ground? I was just enthralled and haunted and, you know, it continues to be so. It’s one of those stories.

Years later I was a little surprised to not run across it in my formal Zen training, proceeding through the Harada Yasutani koan reform of the Takujo system of Hakuin koan Zen. Yes, I ran across references here and there in my reading. Master Seung Sahn treats it briefly in his anthology of koans with comments, The Whole World is a Single Flower.” My teacher’s teacher Robert Aitken Roshi cites it in his essay on sexuality in his classic Mind of Clover. But, that was kind of it.

For a while I wasn’t even sure it was properly a koan, as it isn’t anthologized in the three “big” twelfth century collections at the heart of the Harada Yasutani curriculum, the Gateless Gate, the Blue Cliff Record or the Book of Serenity. Then Thomas Yuho Kirchner released his wonderful translation of the Shumon Kattoshu, Entangling Vines, first published in Japan at the end of the seventeenth century, and one of the major koan collections in orthodox Japanese Rinzai. Entangling Vines is itself gleaned from various Chinese anthologies that were popular in that day. And it turns out the original of this koan is collected as case six of the Compendium of the Five Lamps, the Wudeng huiyuan.

Okay, besides being novel, and appealing to a seventeen year old, and maybe the seventeen year old in all of us, what do we do with it? Where is the direct pointing and invitation into intimacy that mark all true koans?

No doubt this one is tricky, in fact maybe more difficult to get through to the heart of it than with many others. There are just any numbers of ways we can distract ourselves under the best of circumstances. And, here it turns on a tale of sex. Right at the start there’s that relationship between the old woman and the young woman she sends out to test the monk. In Master Seung Sahn’s version she’s a daughter. In Aitken Roshi’s version, a niece. I do notice the Venerable Kirchner avoids any reference to the women’s relationship. To my ear there’s exploitation of a youth.

And we should attend. There are so many problems about how women are treated throughout history, and, right now. And it is a real issue how the old woman sends her daughter or niece or whatever off as a seductress. And time should be found for that conversation. And we can take the time we need. The koan will wait. But, it will also bubble and burn and whisper and call, like the embers of that burnt hut, like the tendrils of smoke rising from the ashes of that hut.

Another “trap” for the story as koan, is how there is a pretty straight-ahead moral in the story. For instance the Soto priest Nonin Chowaney summarizes that most common and legitimate view nicely when after warning people they should take up a koan with someone who has properly trained with koans, he writes, “If Zen Buddhist practice has turned our hearts into stone and made us oblivious to human sensations and feelings, we have been doing it improperly.”

Here the case becomes a companion to the old story of the two monks walking and who meet a woman trying to cross a river and having trouble navigating the current. The one monk picks her up, carries her across, sets her down, and the two continue on. As you know the story ends with the moralizing “I put her down at the bank of the river, you’re still carrying her.”

Useful.

I do think this sentiment has elements of what we’re looking for in this story as koan. For instance when one of Hakuin’s more famous lay disciples Satsu’s granddaughter died, she was overcome with grief. A neighbor rebuked her, noting how she had Hakuin’s certificate of enlightenment, so, how could she be carried away like that? She replied, “Poor fool! Don’t you see how my tears are better than a priest’s chants? My tears remember every child who has died.” She concludes with the great pointing, “This is me at this moment.”

Returning to the question of respecting the person who is present, there is something that offends the heart in the callousness of the monks rebuke of the girl. And, sadly, it is something not that uncommon among those who throw everything into the path. But also a terrible dead end. I find myself thinking of Gore Vidal’s novel Creation. It offers an important variation on the two monks and the woman and the river. Creation opens with an aged Persian ambassador to Athens incensed as he hears Herodotus lecture on the Persian wars and decide to provide his own reminiscences of recent history, much of which he witnessed at first hand.

The putative author of these memoirs is the grandson of the prophet Zoroaster. Thanks to this privileged condition, he found himself everywhere that counted in what the scholar Karen Armstrong calls the Axial Age, a period of something less than two hundred years that birthed most of the world’s religions. Vidal’s conceit is to shrink that era a little to put them all within the range of his ambassador’s very long life.

So, from when the story begins where he watches his young stonemason Socrates building a wall that keeps falling down, he relates stories of meeting them all, from Mahavira to Confucius. But, it was his interpretation of the Buddha that I find myself reminded of. The ambassador recounts how the Buddha would look right through him when they were talking. Apparently, well, according to Gore Vidal, the Holy One was in the habit of gazing into the middle distance rather than making eye contact with any person.

Sometimes people think spirituality means cutting us off from life. Certainly here we get that is the monk’s mistake. Or, one of them.

Clearly, with the story of the old woman and that monk we see we’re being invited in another direction. Or, I hope we do.

Aitken Roshi says he’s only found two koans that touch on sexuality. This is one. The other is collected in the Harada Yasutani Miscellaneous koan collection as the third question of Sungyuan’s Three Turning Words. “Why is it that someone of great awakening does not cut off the vermilion thread?” The roshi’s comments “the vermillion thread (is) the line of blood itself – the line of menstruation, sexuality, and birth.” I would throw in of death, as well. The whole thing. Messy. Sometimes unpleasant. Sometimes pleasant. Always compelling.

One venerable commentator on the “old tree on a cold cliff,” line the monk said in response to the young woman, that if he had had that encounter, a green sprout would have appeared on that old tree.

Messy. Sometimes unpleasant. Sometimes very pleasant. Always compelling.

And, all this said, acknowledge, and maybe even dealt with to some degree, finally, here, I suggest, we find the koan of this koan.

What is your life? What do you feel? What is it that races through your heart and your mind?

Where is your body in this story?

Where is your body in this story? Is there any part you do not play? Old woman? Girl? monk? How about the hut?

That’s the stuff of your work, my work, our work.

As our teacher master Hakuin once said, “meditation in action is endlessly more important than meditation in stillness.” And in the action, that’s where the koan is revealed.

Of course it isn’t an invitation into licentiousness. I hope “of course.” I fear it isn’t always. Nor is it an invitation into prudery, or denial, or a life of gazing into the middle distance. There are appropriate and inappropriate actions in our lives. Think of it as a dance. And within the dance we all must relate to each other as precious and as valuable as I hope we come to see we are, each of us, as we are. Meditation in action.

As we are.

We do this and truths reveal themselves.

For one, all of us belong to that same great boundless family.

One thing, empty, and bright.

And, that other thing reveals, too. You and me, just as we are, just as we are. Fleshy and messy.

Angry? Lustful? Forgetful? Shy? Aggressive?

Name it as yours, know it, really know it.

It is the Buddha way presented,

It is the Buddha way.

Here, with this racing heart. Here, with my own actions and their consequences, it is all revealed.

No place else.

In the monk. In the old woman. In the girl.

In the burning of that hut.

Smoke rising.

Smell those ashes.

And feel the sap rising, ready to send out a new branch.

Look.

Feel.

Right here.

Right here.