It was on this day in 1717 that Benjamin Hoadly, the Anglican bishop of Bangor preached a sermon before a congregation that included the king, George the 1st. It was in large part a response to the late Anglican divine George Hikes posthumously published “Constitution of the Catholic Church, and the Nature and Consequences of Schism.” Pretty inside baseball stuff for Anglicans and their tension as both Catholic and Protestant. The bishop’s rejoinder, the sermon preached today nearly three hundred years ago, might have been articulating a heartfelt theological principle, but since that principle was Erastian, that is it advocated the primacy of the state over the church, in its more extreme forms, which the bishop advocated, it meant the church has no worldly authority, at all. Which preached before a king, could be seen as well as heartfelt, as convenient.

Small wonder that Queen Anne was said to have remarked that the bishop would be an ideal candidate for archbishop of Canterbury, if only he were a Christian.

Me, I’m more interested in his eucharistic theology, something I stumbled upon in my seminary years, and which I found compelling. The good bishop explored the value of the rite of communion as a purely human ritual, without any need for appeal to divine intervention; rather, it was an exploration of the power and beauty of human memory.

Throughout its own near three hundred year existence, the First Unitarian Church of Providence has never ceased observing the rite of communion, although it is celebrated only a couple of times a year, and for many years, probably more than a century never as part of the regular Sunday service. It’s greatest focus is on Maundy Thursday. Which this year is this week.

It is also the last time I will celebrate the rite of communion as minister of this church.

While theologically a liberal Buddhist, because I am also the minister of a church which if not Christian, is rooted within the Christian tradition, I have been regularly invited to reflect on the ritual of Christian communion. And I have. And I have in the main relied on the good bishop’s sense that the rite is a memorial service as justification for my participation, indeed, for a largely non-Christian congregation’s participation.

And what memory reveals…

There is something powerful in the rite of communion. And small wonder people have all sorts of ideas about what it means.

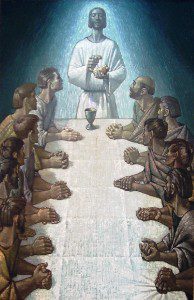

What we have is a meal. Probably the first communion was a Passover meal. I believe so, although there are good arguments against that view. But even if not directly a Passover service, the fact of a sacred meal at Passover no doubt is the indirect if not direct ancestor of the ritual.

And, a sacred meal is in fact much older and vastly more common than the Jewish celebration.

It’s a human thing, to eat and notice the holy.

And for me the secret sauce is our human memory. We recall the meals of our lives. We recall, perhaps, when we didn’t eat. We recall the joys and the sorrows at those, hopefully many meals we have eaten.

And they are all captured, past, and present, and future, in a few minutes of shared time and food and drink.

And, this is important, company.

A mistake I think in some Christian communities is the solitary celebration of communion by a priest.

This meal is meant to be shared.

Here our sacred individuality and the reality of our interdependence is fully presented.

All we need is to join with others, share food and drink, and recall. To do this is to open our minds and our hearts, and be present to what is.

A good thing.