In recent years, the author Neil Gaiman has been getting quite a bit of attention due to the adaptations of his work, from Amazon’s pitch perfect rendition of “Good Omens,” his collaboration with Terry Pratchett, or from the considerably more problematic adaptation of “American Gods,” currently running its third season on the STARZ network. But no adaptation has received more anticipation, speculation and excitement than the work that put Gaiman on the map in the late 1980s, the comic series “Sandman.” Recent casting announcements, after decades of failed attempts to bring “Sandman” to the big or small screen, have raised the flames of anticipation even higher as the forthcoming Netflix series enters production soon.

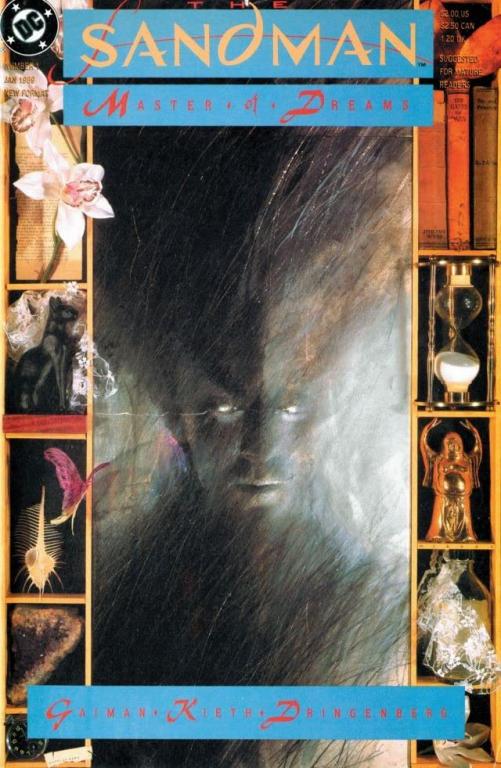

To properly provide the occultural context for “Sandman,” it’s important to recognize the fact that the comic series, which originally ran from January 1989 to March 1996 in 75 issues, is probably one of the most well known artifacts of popular occulture of the late 20th century. The series was also significant for having the most adult readers and the most female readers of any comic title at the time, which Gaiman acknowledged and celebrated.

Preludes and Nocturnes

Often descriptions of “Sandman” mischaracterize it as a “graphic novel” (Alan Moore’s “Watchmen” is similarly categorized incorrectly). And while there have been some specific “Sandman” graphic novels, the main narrative was a series of single comic issues, first with DC Comics and then moving over to Vertigo, DC’s more adult imprint that closed down just last year. These issues were later collected into trade paperbacks, switching between extended story arcs and stand-alone single issue “short stories.” Therefore, most people are familiar with these trade collections of story arcs, the first of which was the collection entitled “Preludes and Nocturnes,” consisting of the first eight issues of the series.

It is this first collection, published from 1988 to 1989, that is heading for adaptation as the first season of the upcoming Netflix series. For those of you unfamiliar, “Preludes and Nocturnes” is the story of Dream of the Endless, a family of archetypes (including Destiny, Desire, Delirium, Death, Despair and Destruction), and how he is accidentally trapped by an occultist for decades, the consequences of Dream being away from his station as the lord of the Dream world, and the actions Dream must take to reclaim that station after he eventually breaks free.

Over the run of the comic, however, that more straightforward narrative style varied considerably, to the point where Dream, also known by his Greek name Morpheus, Lord of Sleep, and in popular folklore as the Sandman, was often not the main character in his own series. Indeed, Morpheus would remain in the background as an influential but mostly hidden presence in favor of other characters who would attempt to navigate his realm, such as Rose Walker of the collection “A Doll’s House,” or Barbie of “A Game of You.”

Ultimately, Gaiman’s “Sandman” series was a story about stories, with the central mysterious figure not as the storyteller himself, but rather as the archetypal inspiration for all storytellers. It is no coincidence, then, that the first “Sandman” story is thoroughly entrenched in the occult world. And there are several reasons for that occult setting.

Magicians of Horror

First, it’s important to note how Gaiman sees himself in the realm of occult fiction. Unlike fellow British Invasion comic writers from the late 80s, Alan Moore and Grant Morrison, who presented themselves as self-made occultists and magicians, Gaiman makes no such claims. Back in 1994, during the creation of his graphic novel “The Books of Magic,” which would go on to be another popular Vertigo ongoing series by another author, Gaiman was interviewed alongside Rachel Pollack, trans activist, esotericist, and comic author, about their use of tarot cards and occult themes in their works. He contrasted himself with Pollack, who had created the Vertigo Tarot deck, calling himself a “dabbler and voyeur” who regards the esoteric as a “delightful playground” for creating stories. Thus, Gaiman is the bard rather than the magician.

In fact, one could say that given how magicians are presented in “Sandman,” it’s safe to say that Gaiman is skeptical, if not outright critical.

All the stories of “Preludes and Nocturnes” indulge in the horrific possibilities involved in denying people the ability to dream and process their inner demons. Further, the series explores what mere humans would do with the tools reserved for the Lord of Dream, as well as what kind of revenge a being of that kind of power would wreak on those who would attempt to control it. In fact, issue #6, “24 Hours,” remains one of the single most disturbing issue of a comic book ever produced by a mainstream publisher, in which an insane supervillain traps victims in a diner and removes their inhibitions one by one. Oddly enough, the tool used to perform these deeds, stolen from Dream, was recently referenced by Wonder Woman: 1984.

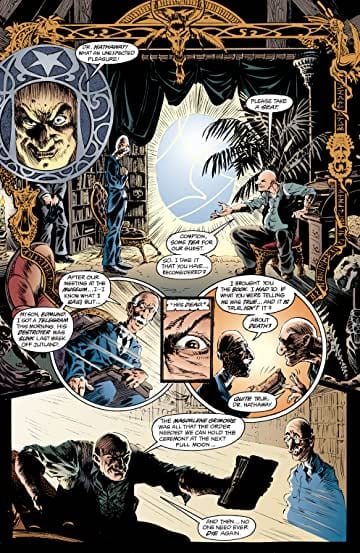

When the story begins, however, we are firmly established in the occult world. When Morpheus first appears, it is in the dingy basement of a mysterious British castle in 1916, where he is trapped in a magickal circle covered in occult symbols and runes. Again, making it clear that the comic itself is a meta-reference to occult stories, the artwork is framed on the page by an outline of demonic images and occult symbols, creating almost a proscenium stage to contain the story unfolding.

The magician who is at the head of this operation is the ambitious Roderick Burgess, who makes a comment about how “after tonight, I’d like to see Aleister and his friends try to make fun of me,” undoubtedly referencing Aleister Crowley, the historical archetype for the early 20th century occult magician. And for the upcoming Netflix show, it was announced that Burgess, who only appears in the first issue of the comic, is to be played by the always compelling Charles Dance (Tywin Lannister himself!), so we know that they’ve got the stereotypical evil magician character set.

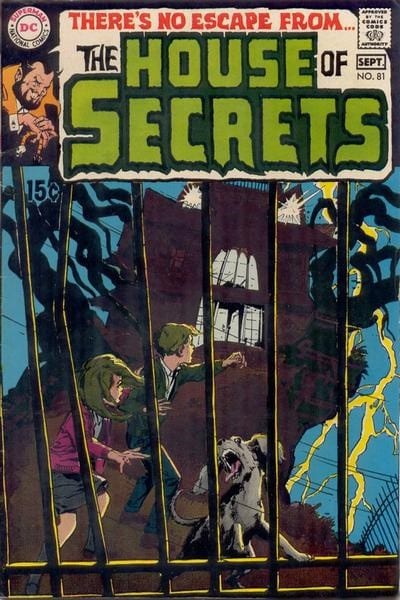

From the outset, Gaiman’s comic was deeply steeped in the macabre horror traditions of the Bronze Age DC titles, a style further invoked by the unsettling, melting artwork of Sam Kieth and Mike Dringenberg. These titles, including “House of Mystery,” “House of Secrets,” “The Witching Hour,” “Secrets of the Haunted House,” and many others, were essentially DC’s post-Comics Code attempt to evoke the glory years of the gory, hilariously over the top EC Comics from the 1950s, the most famous title of which was “Tales from the Crypt” with its endlessly punning crypt keeper “host.” It was these comics that were partially responsible for the strict Comics Code that the industry brought on itself, disallowing violence, gore, disrespect for authority, any supernatural creatures, or even mention of the words “terror” or “horror.” When the Code began to relax in the mid 1970s, DC brought back these concepts through their myriad horror anthology series.

Though many of these were short-lived, a few titles lasted for quite some time. One of these was the “House of Secrets,” which produced the first ever Swamp Thing story in their 92nd issue, before the creature got his own 70s era title. It was a revival of one of these Swamp Thing titles that Alan Moore famously took over and re-shaped, laying the foundation for what would become Vertigo Comics in the late 1980s, and making Gaiman’s “Sandman” possible as a title to begin with.

Stories About Stories

Of course, over the 75 issue run, not to mention a legion of spin-offs, not all of them written by Gaiman, the macabre EC style eventually gave way to an incredibly diverse approach to storytelling and artwork, though the occult roots of the story were always there. One of the most famous single issues later in the series was #19, “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” which depicted William Shakespeare’s theatre company giving a performance of the titular play in the English countryside to an audience of actual faerie creatures, led by the real Titania and Oberon. The issue stirred up some controversy when Gaiman won the 1991 World Fantasy Award for Fiction, being the only winner before or since, to win the award for a comic book.

In the comics, we see Shakespeare make a deal with Morpheus for inspiration and he returns at the end of the series with references to “The Tempest.” Here, as in other areas of the story, it’s clear that Gaiman is focusing on the art of storytelling as magickal practice itself, implying that Dream is behind all great stories. And this works on several meta-levels.

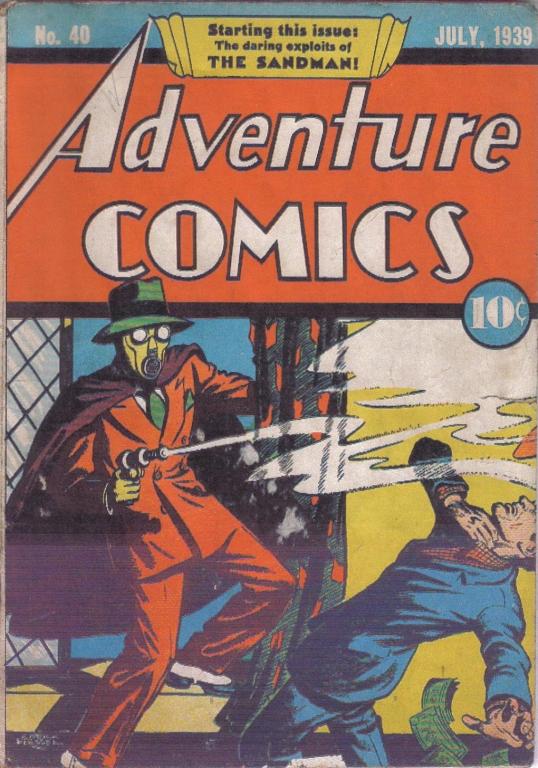

The original Sandman character was a Golden Age 1930’s “mystery men” character with no superpowers who would fight crime with a gas mask and a gun with sleeping gas. Part of Gaiman’s genius is his ability to play with large mythologies, particularly with retroactive continuity. In his version, the Golden Age character is inspired to take on his superhero persona because the dreams of the actual Sandman, Morpheus, are leaking out as he’s trapped in Burgess’ basement during the 30s. Even his gasmask suggests Dream’s powerful helm. This also explains later iterations of the character, including Jack Kirby’s ridiculously spandexed superhero version from the 70s, who also makes an appearance in Gaiman’s series.

And most of the denizens of Dreams’ realm are little known characters from other DC comics, including the raven, Matthew, who is a resurrected version of Matthew Cable from “Swamp Thing,” Lucien, the librarian of all the unwritten books ever imagined, who “hosted” “Tales of Ghost Castle” (1975), and of course, Cain and Abel, the unfortunate Biblical brothers, who “hosted” “The House of Mystery” and “The House of Secrets,” respectively.

In fact, almost all of these ancillary characters served as storytellers themselves in their DC series. The crone Eve was the host of “Secrets of Sinister House,” the Furies narrated “The Witching Hour,” and the list goes on. Even Dream’s enigmatic older brother, Destiny, who is blind but reads from the great Book of Destiny in the “Sandman” series, was originally the host of a DC anthology comic, “Weird Mystery Tales.”

Therefore, Gaiman not only draws on the mainstream superhero DC universe with the creation of his character, he builds his own universe from the established world of DC horror comics and their “hosts,” which themselves were meta-references to old radio and television hosts who would scare listeners and viewers with their terrifying tales.

New Storytellers

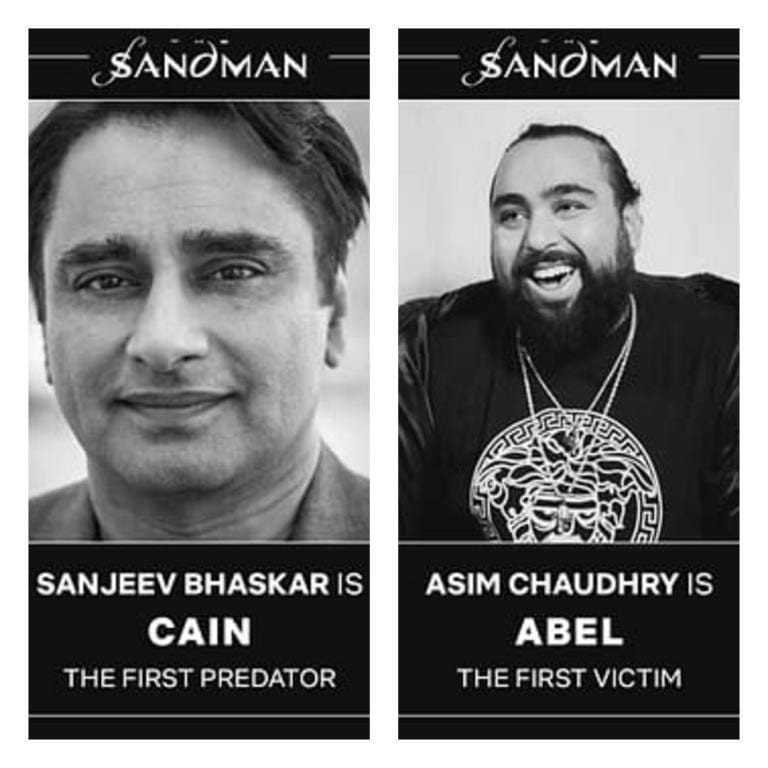

And here is where the recently announced casting gets interesting. While Dream gets a somewhat predictable but satisfyingly mysterious young British actor with pale features (Tom Sturridge), some of the other characters get some interesting choices. First, we get the statuesque Gwendolyn Christie (another well known “Game of Thrones” alum) as Lucifer. More on her in a minute. But we also get Cain, Abel, and Lucien, Dream’s lackeys, all drawn in the comics as somewhat feral-looking bearded and bespectacled white men. Here, they are being cast as two South Asian men (comedians Sanjeev Bhaskar as Cain and Asim Chaudhry as Abel), and a Black woman (Vivienne Acheampong as Lucienne).

Given that there’s very little chance (or reason) that the Netflix show wants to explore 1970s era DC horror comics, the characters of Cain, Abel, and Lucien are free to be released from their roots as DC legacy characters. Therefore, other mythologies can be explored. Billed in the announcements as “the First Predator” and “The First Victim,” it seems we are exploring Cain and Abel even beyond their biblical roots, perhaps implying references to the rich storytelling traditions of India.

In the comic itself, we often see Morpheus appearing in countless different forms, to other cultures, races, even to animals (“A Dream of a Thousand Cats”) and alien species (“The Sandman: Overture”). Therefore it’s already baked into the concept that Dream is a universal concept and can change forms based on who is regarding him. Perhaps the show will lean into that concept just a bit more than the comic did. At the time, Gaiman still assumed a predominantly white readership, since we still see Morpheus primarily as the standard goth dude. Given that in recent interviews, Gaiman has made it clear that the show will be set in the 2020s and not a period piece, and that he has welcomed the challenge to reframe the stories to take into account how our cultural thinking has changed, one hopes that this is one of those challenges he considers.

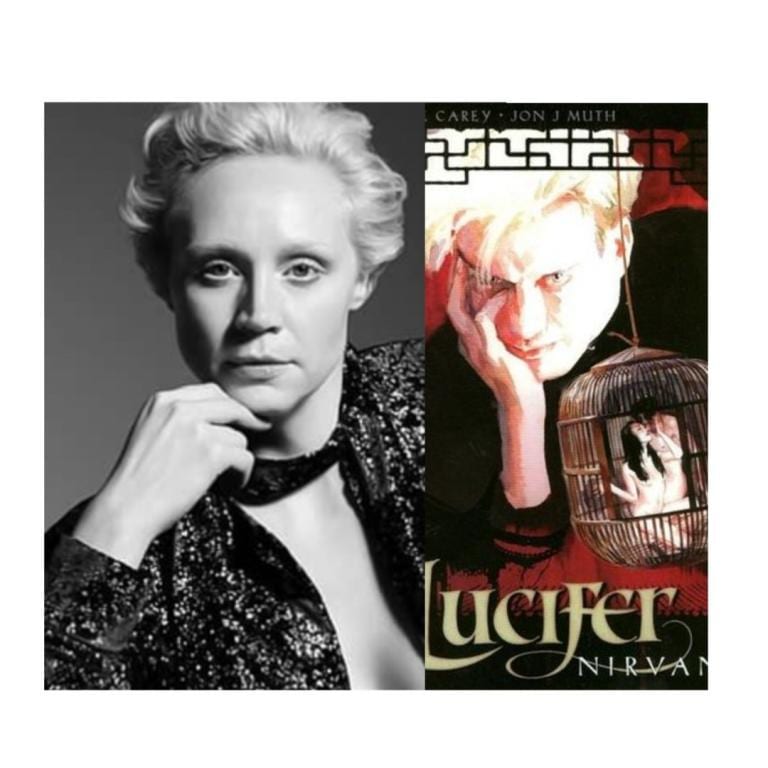

The casting of Gwendoline Christie as Lucifer is one indication that Gaiman is moving in the right direction. Of course, Gaiman’s version of Lucifer already has an avatar in the form of Tom Ellis on the (formerly Fox) Netflix show “Lucifer.” However, Ellis’ Lucifer, as conceived by the Fox showrunners, is quite a different character, delicately balanced between smarmy and charming, self-obsessed (and just plain obsessed), desperate to be adored and needed, teeming with abandonment and daddy issues. Whereas Lucifer as Gaiman imagined him, and later as the brilliant Mike Carey imagined him in his own series that spun-off from “Sandman,” is otherworldly, aloof, menacing, utterly amoral, and immensely powerful.

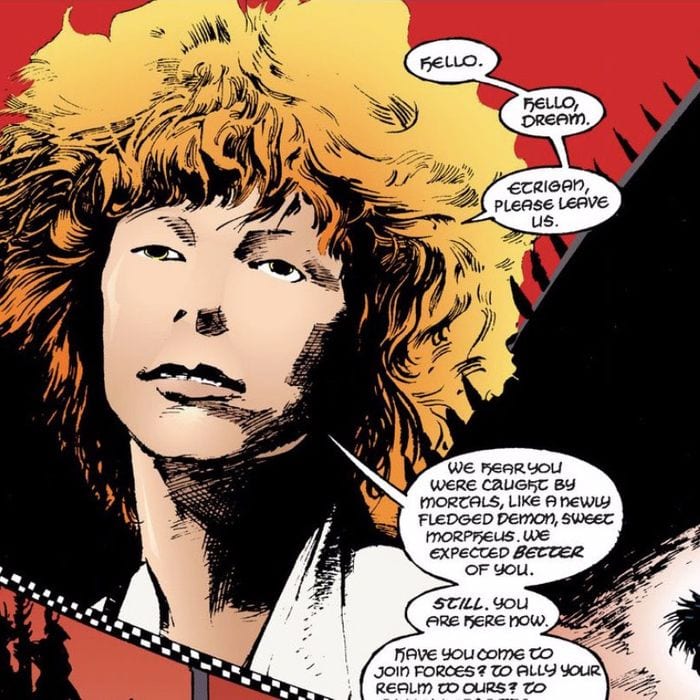

Christie perfectly embodies these characteristics in a way that transcends gender, just as Tilda Swinton did in the lesser role of Gabriel in the Keanu Reeves-led “Constantine” movie (2005), which had its own Lucifer in the form of Peter Stormare. Continuing the odd coincidences, Kieth and Dringenberg’s original depiction of Lucifer in “Sandman #4” is undoubtedly based on early pictures of David Bowie, who Swinton worked with in 2013 and to whom fans have connected Swinton very closely. Further, since Constantine appears as a crossover character in “Sandman #3,” it looks like we might get another version of the Liverpudlian occultist besides the one currently on “Legends of Tomorrow” (played by Matt Ryan), if I’m reading Gaiman’s recent tweet correctly.

Burning Desire

But the idea of cross gender casting, as established with Christie and Acheampong, will present, in my opinion, one of the biggest casting challenges the show will have. I don’t mean with Death, whose casting has not been announced yet, but is usually depicted as an iconic goth teen, imitated by young women with big, dyed black hair, eyeliner and ankh necklaces everywhere. That one probably has the most riding on it, due to the fact that it’s the most recognizable character from Gaiman’s mythos, with much merchandising and spinoff potential.

No, I’m talking about Desire, the other well known Endless character, originally depicted as an androgynous Patrick Nagel-esque painting. In the comic, Desire is presented as both male and female, but I personally wonder if the show will take the more obvious route of casting an attractive androgynous cis-woman (back when a 90s film was in development, Angelina Jolie was rumored to be attached), whether they’ll go for a more gender fluid actor like Ruby Rose, or whether they will take the braver step of casting an unknown non-binary trans actor.

And this undoubtedly reminds “Sandman” fans of one of the more controversial aspects of the comic’s 75 issue run: the character of Wanda in “The Game of You” story arc and collection. One of the first trans women in mainstream comics, Wanda was probably one of Gaiman’s more progressive creations for the time, but looking at the comic by today’s standards reveals quite a few shortcomings and problems that Gaiman himself has acknowledged.

So I’m very curious how the continued casting will play out, as one hopes the show will get to cover all the major story arcs from the comics.

As a prominent part of popular occulture, Sandman offers pleasures for the reader (and hopefully, viewer) that are unparalleled, connecting the human gift of storytelling to oral tradition, mythology, theatre, the superhero genre, the comic book medium as a whole, and beyond, to dreaming, the imagination, and magick. We meet faeries, gods, nightmares, monsters, demons, superheroes, magicians, cosmic archetypes and very imaginative humans.

And pop occulture fans couldn’t be more excited to see what’s in store for us on our magical screens as these stories come alive.

If you’d like to read more about Neil Gaiman and his use of occult tropes in works such as “Books of Magic” check out my essay in the 2011 anthology “Supernatural Youth: The Rise of the Teen Hero in Literature and Popular Culture” by Jess Battis. My essay is entitled “Enrolling in the ‘Hidden School’: Timothy Hunter and the Education of the Teenage Comic Book Magus.”