Warning: This post contains massive spoilers for the most recent season of “Star Trek: Discovery.”

With the events of the last two weeks, I haven’t had a chance to write about the season finale of “Star Trek: Discovery” that came our way recently. Even though we are looking at a new Presidential administration this week, we are far from clear from the problems of 2020, indeed, the last four years. We, as a nation, and in some ways, the world, have been going through a collective trauma. And that’s exactly what I saw reflected on the screen with the latest season of Trek. And while “Discovery” isn’t the first program to explore themes of trauma through genre allegory, this particular show resonated deeply with me and reflects so well where we are in early 2021.

Now, I know Trek isn’t exactly “occult” (except for that awful “Catspaw” episode), but if there’s one thing that Pagans can agree on, it’s that sci-fi/fantasy fandom is a major thing with many of us, to the point where we approach our fandom almost religiously. Personally, I like all things Star. Wars, Trek, Blazers, whatever, they all scratch different itches.

And while my interest in “Star Trek: Discovery” as a program had previously been somewhat lukewarm, this recent third season has kicked it into high gear. Now, your mileage may vary. I’ve heard many complaints, some valid, about how the new Trek shows promote style over substance, that people miss the standalone episodic structure of the 90s shows, that the lead character Michael Burnham is too important and too good at everything (what my friends and I used to call “the best damn pilot in the fleet” syndrome, based on the Starbuck character in the “Battlestar Galactica” remake). But damn if I haven’t fallen for the crew of the Discovery, especially the lovely queer family of Stamets, Culber, Adira and Gray, featuring the first trans and non-binary characters, as well as the first openly gay couple, in Trek history.

However, it was the overarching storyline of season three that nailed it for me. It’s one of those things in which the writers and producers couldn’t possibly have known how resonant their work would be, having made the show long before its airing in late 2020. In watching this recent finale, it struck me that the writers must know their way around depth psychology, as the entire season is an allegory for collective trauma, our responses to it individually and culturally, and the possibility of healing.

If you’re not aware of the premise of this latest Trek iteration (and its streaming on CBS All Access has definitely limited its viewership) – well, I’m going to spoil a whole lot for you. The show started as yet another Trek prequel, set just before the events of the original series, ret-conning somewhat haphazardly, making the lead, Michael Burnham (Sonequa Martin-Green, replacing Sarah Michelle Gellar as the new SMG) Spock’s previously un-mentioned adoptive sister, having the leads interact with the crew of the Enterprise before Kirk in the second season, and generally rewriting everything from the technology of the time to the look of the Klingons, much to the chagrin of continuity obsessed fans.

At the end of season 2, the show came up with an explanation for why these characters and this ship were never mentioned by later Trek shows: they make a jump to the far future for reasons and the Federation (and Spock himself) vows to erase all mention of the ship and its crew from their records. Season three opens in the immediate aftermath of this 930 year time jump.

While the Discovery crew and our lead, Michael Burnham, are initially separated for a year, they independently discover that this Trek universe underwent a cataclysmic event over a century prior: something called “the Burn” that affected all ships carrying a dilithium-based warp core, and depleting the galaxy’s dilithium supply.

What this means, effectively, is that warp drive is no longer a thing for the most part, pockets of the various quadrants have become utterly isolated, the Federation is a mere shadow of its formal self, and oligarchic criminal enterprises based on slave trade, like the “Emerald Chain,” have propped up in its place. At the beginning of the season, Federation outposts can’t even communicate with each other because long range sensors are affected. We later find that the Earth has left the Federation and are actively hostile to it, waging war with what it thinks is an alien race, but is actually abandoned human colonists (“People of Earth”). Most other Federation planets have left or are cut off from their fellow planets. Eventually the Discovery crew finds the heart of what’s left of the Federation, led by the weary, and wary, Admiral Vance (Oded Fehr).

Thus, “Discovery” leans into its themes of isolation and disconnection, emphasizing the fear and distrust that have overtaken the cosmos in the century since the Burn. The crew has to overcome those tensions within itself in the same episode as the new character Adira has to come to terms with the Trill symbiote inside of them (“Forget Me Not”). I found this episode probably one of the most beautiful episodes I’ve ever seen in the history of Trek, that focuses on Adira fully embracing not only the multiple entities of their Trill symbiote, but also their non-binary identity.

But what we see as a whole is a universe broken by isolation, fear, distrust, division, lack of communication and connection. People across various planets and species are hurting deeply. Every time one of these themes emerged across the thirteen episodes of the season, I found myself profoundly moved by how well it reflected our current state of mind in late 2020/early 2021. After almost a year of the pandemic and various levels of quarantine, we’ve all felt isolated, disconnected, wistful for the “before times.” We’ve all experienced fear and distrust based on deep divisions that have been so widely amplified in the Trump years.

Now I acknowledge there’s a whole political dimension that I’m not even touching here, in which the Federation is dubiously cast as a benevolent power, a colonizing status quo that still polices various societies and wants to regain that status. Critiques of the show as a neo-liberal fantasy softened by the presence of queer characters and people of color in leadership roles are probably not that off base.

However, I found myself deeply invested in the Discovery crew’s quest to find the source of the Burn, to reconnect societies, to heal divisions, and to once again offer up hope to the galaxy.

They eventually do find the cause of the catastrophe, and without getting too bogged down in the technobabble (something to do with how his DNA interacts with dilithium or whatever), it comes down to a Kelpian (the same race as Discovery’s captain, Saru, played to perfection by the sublime Doug Jones), who has been trapped in an elaborate holo program for over a century yet still functions more or less like a child.

The Kelpian, Su’Kal (the always genius Bill Irwin) apparently has been in this program so long, set up by his dying mother as she and her family succumbed to radiation poisoning, that he has no idea what the outside world is like, or even that he is in a program. When members of the Discovery crew infiltrate the collapsing ship and enter the program, they appear as other species (and for the first time, we get to see Jones’ very expressive but usually heavily prosthetic face as human). We also get a fantastic moment where Gray, part of Adira’s Trill symbiote and usually only visible to them, becomes visible to everyone else through the program (“You can see me!”).

We further learn that a seemingly malevolent force in the program is actually a figure from a Kelpian children’s tale that teaches a lesson that you have to face your shadow and confront your fear before you can grow. Sound familiar?

Over the course of the season’s final two episodes, Saru and Dr. Culber (Wilson Cruz) help Su’Kal gradually come to terms with the fact that his constructed reality is just that and support him as he faces the traumatic memory that triggered his extreme emotional reaction, which in turn, caused the Burn: witnessing his mother’s death and his subsequent abandonment.

And here, I’m noticing, once again, we are dealing with a character navigating a fake reality. Unlike the malevolent Blackwood on “The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina,” who uses a magick wish to gain power, Su’Kal is truly an innocent, surviving with the help of a collective artificial intelligence that his mother has created for him to cope with being alone. But as Saru eventually explains to him, Su’Kal’s mother never intended him to stay in the program for over a century. The holo training was always meant to prepare him to interact with the real world. And of course, the fact that the ship is now collapsing around them, leaking radiation, lends some urgency to the proceedings.

And of course, all this happens while an intense Trek action movie is taking place back on Discovery. But the key to the season’s theme lies with the Kelpians. When he does come out of it, Su’Kal wants to make amends. Saru agrees to help him, yet reassures him that what happened is not his fault, ending the episode showing the traumatized Kelpian the sights of his homeworld, Kaminar, as a deeply caring mentor and caretaker.

Throughout the season, we see the importance of empathy, in terms of how the crew has to literally deal with the trauma of leaving all their family and loved ones behind forever, as well as the dangerous journey to the future that they barely survive. We see this particularly taking its toll on Detmer, one of the under-developed bridge crew characters, who is responsible for piloting the ship. In earlier parts of the season, we clearly see that she is dealing with a kind of PTSD and Dr. Culber has to work hard to convince her to seek help.

In the voice over medical officer log that opens up the emotional fourth episode, “Forget Me Not,” Culber, who had his own experience coming back from the dead in the previous season, describes what the crew of the Discovery is experiencing after some amount of time in the far future:

“It’s starting to hit everyone. Just how little we have to hold on to. The personal moments we use to define ourselves. Birthdays, anniversaries, graduations, funerals. We’ve jumped past all of them. They feel lost, disconnected. I tell them, I’ve been alone. I’ve been lost. Both are survivable. And surviving can become living again.”

I can’t imagine a better description of what we’ve all gone through during the pandemic. I get weepy even replaying that one scene. That the writers were so prescient, crafting this before the pandemic was even a thought, is nothing short of incredible.

Culber later notes that the crew’s goal of finding the Federation again gives them the only hope they have. Here again, I was struck by how resonant this felt: the notion of returning to a central authority who you can trust, knowing that someone competent is in charge, perhaps a presidential administration that knows how to handle the pandemic. This particular episode aired on November 5, when we were still uncertain who won the election.

Of course, when I look closely at that longing to have faith in one’s government again, I know I’m being somewhat naïve, but there was definitely something primal in hoping for healing after all that we’ve been through since 2016. And the fact that the same episode also beautifully affirmed the identity of its trans characters, after we’ve seen LGBTQ rights erode in this country over the last four years, was especially compelling.

In other instances in this season of “ST:Disco,” we see evidence of empathy from Saru towards his crew, of Tilly towards Georgiou, of all people, and the fact that Michael’s partner in future hijinks, Cleveland Booker, comes from a race of beings who can literally connect with other species through biological empathy. So much so, that when we see Book’s home planet in the eighth episode, “Sanctuary,” we see him interact with other men in a way that I thought at first that the show was hinting he might be bisexual. But no, this is actually what non-toxic masculinity can be.

Regardless, the theme is clear. Only through empathy and confronting our own responses to trauma can we heal and move forward.

That got me thinking about other shows that have tackled trauma. In the past year alone, we’ve had “Lovecraft Country” looking at racial and generational trauma, “Umbrella Academy” looking at family trauma and how it manifests through a superhero narrative that could literally destroy the world. A year earlier, Damon Lindelof’s “Watchmen” limited series juxtaposed the responses to the horrific “squid” event at the end of Alan Moore’s graphic novel to the very real legacy of trauma from the Tulsa massacre of 1921. In the series, the characters are constantly living under the shadow, even 35 years later, of an event that rocked the psyche of the world. But it’s the Tulsa trauma that most drives the world’s first superhero, Hooded Justice.

And of course, Damon Lindelof is no stranger to basing tv shows around world changing traumatic events. His masterful HBO series, “The Leftovers” (2014-2017), was built around a rapture-like event called “The Sudden Departure” in which 2% of the world’s population simply disappear with no explanation ever given in the show. Over three seasons of incredibly somber and depressing episodes, the show explored how the world would cope with such unspeakable trauma, as individuals, communities and society as a whole. In my viewing experience, unlike most shows that get darker as they go, “The Leftovers” starts dark and gradually uplifts its characters in unexpected, painfully earned ways.

It’s also important to note that Lindelof’s earlier claim to fame was as a co-showrunner to that glorious mess that was the cultural phenomenon, “Lost” (2004-2010). Part of that “mystery box” (an occult concept if there ever was one) trend popularized by J.J. Abrams, “Lost” tended to focus on the individual traumas that its wide variety of characters experienced in their own lives, in order to tell the story, somewhat haphazardly, of their collective experiences on the mysterious island.

Another show that was popular at the same time as “Lost” was the updated version of “Battlestar Galactica” (2004-2009), that involved a community of people severely traumatized by the near-annihilation of humanity by the Cylons, trying to survive and thrive at any cost. And in the course of the show, it turns out that the robotic Cylons have severe parental issues, and we eventually see their side of it. While so many people complained about the ending of BSG (just as they did for “Lost“), I remember feeling satisfied that the characters had earned their reprieve by the end with everything they had been through.

However, it was the first episode after the BSG pilot, the harrowing “33,” that solidified the show as a depiction of the constant stress, fear, and (of course) trauma involved with wartime and terrorism. Both BSG and “Lost” emerged from a very particular post-9/11 moment of fear and paranoia, where writers were exploring how a society changes, evolves, and struggles after a traumatic event that changes everything.

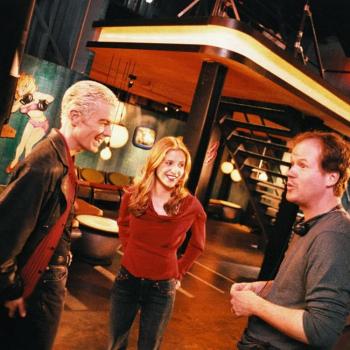

And while it’s not about a society, but a very close knit community group, no show reflected the underlying unease, withdrawal, isolation, and trauma responses of that time than the notorious sixth season of “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” For that season, Buffy is dealing with the severe trauma of readjusting to life after sacrificing herself, dying and being resurrected against her will (“I think I was in heaven“), Xander leaves Anya at the altar, Spike almost rapes Buffy, Dawn melts down, and of course, Willow famously loses her shit after Tara is accidentally murdered.

Like the case with ST:Disco, BTVS’ season 6 was written before 9/11, with its initial episodes premiering in October 2001, yet what the country went through in the aftermath of the national trauma is reflected deeply in the characters’ individual struggles that season. And while much has been made about how season 6 prefigured important conversations about the toxicity of geek culture, the “darkness” of season 6 is rarely discussed in the context of 9/11.

I think fans viewed that season so negatively at the time because of what we were all going through. And that’s how it works. Art, music and film tend to land differently depending on what is happening in the world at the time. And if you’re tuned into that zeitgeist, you can’t help but see it reflected in how you analyze a cultural artifact.

And that’s not a trend going away any time soon. As the MCU continues after an almost 2 year absence, our first glimpse, with “Wandavision” (which just aired its first episodes on Disney +), hints that the main character, Wanda (Scarlet Witch) is somehow using her powers to cope with loss. Marvel Cinema’s guru, Kevin Feige, has noted how the upcoming Marvel properties will address “the Blip,” in which half the world’s population returns after the Thanos snap in the “Infinity War”/”Endgame” films, revealing that it will reflect our experiences with the pandemic.

During this last year of isolation, as many of us have turned to tv binging (for better or worse), it can be a comfort and even an opportunity to address issues and heal, through shows that resonant so well, personally and societally.

The voice over monologue given by Michael Burnham at the end of the season finale of “Star Trek: Discovery” is worth citing:

“Disconnection. That’s how this future began. One moment in time radiated outward, until no one even remembered that connection was possible anymore. But it is. The need to connect is at our core as sentient beings. It takes time, effort and understanding. Sometimes it feels impossible. But if we work at it, miracles can happen.”

Like Su’Kal, we were never meant to stay in isolation forever. We don’t have to be trapped in the moment of our trauma, in denial, not confronting what we must.

I can only hope that Burnham’s optimistic sentiment here will lead us through the rest of the pandemic and into a future beyond it.