Warning: Contains spoilers for the “WandaVision” series.

I have to admit, I hit a wall there for a while. I started this blog back in late December, knowing I’d be doing something a little different than most of the Patheos Pagan blogs. I’m not teaching you spells or discussing Pagan beliefs as such, not even commenting on the broader community on the whole, but rather looking at popular culture and media through a somewhat Pagan and occult lens. My years of teaching about “occulture” from an academic standpoint, even as an erstwhile practitioner who still maintains deep ties to the community, contributed to a somewhat insider/outsider viewpoint on these topics.

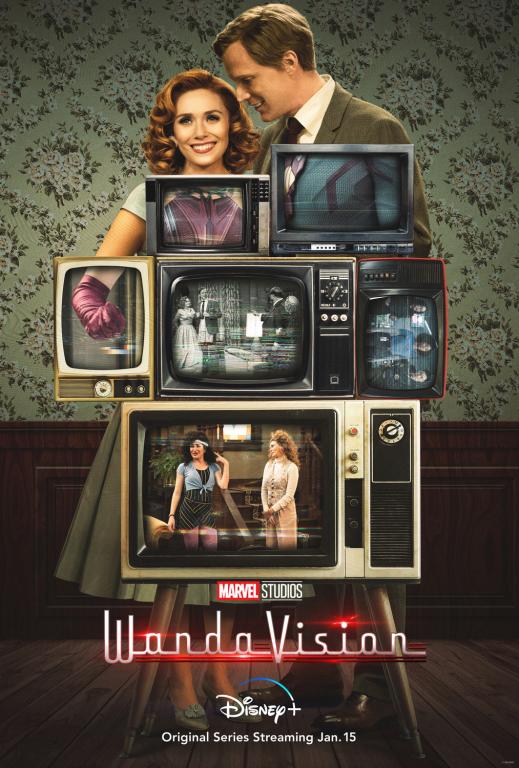

I confess I began to doubt my approach had a place in a pandemic-affected culture, wondering if there was any purpose philosophizing about television, media and “pop occulture.” And then came “WandaVision,” breaking through the hex of my reality like a ton of bricks.

Not too long ago, I wrote a piece on “Star Trek: Discovery” and how the writers and showrunners were ultimately prescient about how resonant the themes of isolation and reaching out for connection would be for viewers during the pandemic, made doubly so due to the fact that the situation of isolation emerged from a very real trauma response experienced by one of the characters in that universe.

And here we are again, but this time it’s a main character – someone who has suffered an intense loss (several, in fact) and whose innate, perhaps even biological power, processes that trauma by literally changing the universe around them. Unlike ST:D’s Su’Kal, whose one time trauma response wreaked havoc across the universe, mostly at a great distance, Wanda Maximoff’s response is painfully local, intense, intimate and ongoing.

As I finished the show a few weeks ago, I began to wonder to what extent we idolize superheroes who would be utterly narcissistic and abusive if they existed in reality. In WandaVision, we see the effects of the main character’s grief and trauma on everyday people, where manipulative magick is a metaphor for gaslighting. In Wanda’s case, she literally projects her denial on a screen for others to watch.

Which Witch?

But first, let’s take a step back and look at the setup. For those uninitiated in the MCU (the Marvel Cinematic Universe) – and I’m sure some of you are out there somewhere – the main character, Wanda Maximoff was an Avenger, joining the group of superheroes after being experimented on by evil Hydra scientists and manipulated by the robotic genocidal maniac, Ultron. As in the comics, Wanda was initially a villain. While her comics origin came out of the X-Men as a member of the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants (with her later ret-conned brother Quicksilver and father, Magneto), Wanda eventually emerged as an Avenger, but with a problematic character life, which included going insane and killing several teammates (“Avengers Disassembled”), creating an entire alternate reality where mutants ruled the world (“The House of M”) and then taking away the powers of the majority of the mutant population by whispering the three words, “No More Mutants” (“Decimation”).

In the comics, Wanda (aka The Scarlet Witch) was always an extreme wild card, whose reality was messed with by others so much, often affecting her synthezoid husband, The Vision, and her two “children” whose actual existence was never quite clear, that readers could almost sympathize when she started to take control and reform that reality herself.

In the MCU, Wanda (Elizabeth Olsen) and her brother Pietro are orphaned in the fictional eastern European country of Sokovia, the focus of much of the “Avengers: Age of Ultron” film and whose tragic events necessitated the “Sokovian Accords,” the international law which now governs superhero behavior and the source of the conflict between heroes in “Captain America: Civil War” (which contained a scene that showed Wanda accidentally causing destruction and mayhem with her uncontrolled powers).

We know from Wanda’s introduction in “Age of Ultron” that she particularly has it out for Tony Stark, Iron Man, because the missile that destroyed her home and killed her parents literally had his name on it. In that film, she reserves her most intense mind-games for him, offering him an apocalyptic vision of all his friends and teammates dead, somewhat of a premonition of what would occur in “Infinity War” and “Endgame.”

In the Disney + show, we see this actual moment when a Stark Industries missile destroys the Maximoff home, through a magically manipulated flashback, and we also see Wanda, as a child, manifesting her ability to alter reality for the first time, many years before her powers were heightened by contact with the Mind Stone from Loki’s Staff, first introduced in the “Captain America” film as the tesseract, and later being a major part of Thanos’ Infinity Gauntlet.

Of course, to comics fans, this scene could indicate the long-awaited introduction of mutants to the MCU, since we know Wanda has innate ability long before Hydra got their hands on her. And many fans seem to assume this is the route the MCU is going, as the rights to the X-Men have finally reverted from Fox to Marvel Studios.

However, that doesn’t seem to be the case at all, considering how the story unfolded on the show and the involvement of Agatha Harkness, the first actual witch in the MCU.

Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered

Given that this is a superhero universe, it’s not surprising that the MCU would present witchcraft as fantasy superpowers and flashy spells, rather than anything approaching realistic practice, and the typical tropes of fantasy witchcraft, including a secret coven of witches in Salem during the time of the trials, fit right in.

And just as we have ceremonial magicians and occultists in the Doctor Strange world, here is where we are introduced to the notion of magickal power through the realm of witchcraft. We also have the Darkhold book playing a role, which has appeared twice before in two previous Marvel television properties, “Marvel’s Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.” and “Runaways” (the canonicity of both being now up for debate). Interestingly, Agatha refers to the Darkhold as the “Book of the Damned,” a phrase also used to describe the Lovecraftian “Necronomicon.” And given that we know Wanda’s next appearance will be in the forthcoming Doctor Strange sequel, “The Multiverse of Madness,” helmed by Sam Raimi, the creator of the Evil Dead trilogy that relied so much on the Necronomicon, all these connections track.

And while all this confirms the full on 0ccult pedigree of these magick-based Marvel properties, “WandaVision” early on establishes itself within another tradition of popular occulture.

If you started watching the show without any preparation, even if you were already an MCU fan, you could be forgiven for being horribly confused by the first few episodes. The black and white sitcom format, directly paying homage to “I Love Lucy,” “The Dick Van Dyke Show,” and “Bewitched,” with the first episode, “Filmed Before a Live Studio Audience,” being actually filmed before a live studio audience, was enough to throw viewers off for a while. We were presented with straightforward, somewhat mundane stories, even with magical superpowers, with occasional Twilight Zone-esque touches, but no clear clue what was actually happening.

Not until the end of the third episode, inspired by a 70s era “Brady Bunch” style, do we start to get a sense of what’s happening in the “real world” of the MCU. We come to learn that Wanda has manipulated the reality of Westview so much as to appear as a sitcom “broadcast” to the outside world, as discovered by astrophysicist Darcy Lewis (Kat Dennings) and FBI Agent Jimmy Woo (Randall Park), who work with S.W.O.R.D., the government entity tasked with investigating the Westview phenomenon.

The story leans into that meta quality, having Darcy and Jimmy watching the Wanda/Vision “show,” investing in the storyline and “shipping” the main characters. Each episode and time period directly references actual sitcoms, down to the title sequences. As the time periods progress, we get an 80s show whose title sequences references “Family Ties” and “Growing Pains,” an early 2000s “Malcolm in the Middle”-style show, and later, a 2010 homage to “The Office,” “Modern Family” and “Happy Endings” with hand-held camera and documentary-style “interviews” that were so pervasive in those shows.

But it’s the “Bewitched” references, including a version of the animated title sequence, that places “WandaVision” squarely (or should I say, hexagonally) in that meta pop occulture context. As I mentioned in a previous post, Wanda’s magical powers fit into that particular world in a direct way, referencing her role as a typical American mid-century housewife. Much has been written about the original 1960s sitcom in which the magic is seen as a metaphor for the anxieties around women’s power in the age of the nascent second wave feminist movement. And given Samantha’s flamboyant family, queer readings of the show have also been popular.

Here, WandaVision acknowledges those tropes, indulges in them and asks us to have sympathy for Wanda in these situations where she must hide her magic and appear as a normal couple in her traditional neighborhood. But when we learn of Wanda’s agency in the creation of this fictional town, all those assumptions go out the window with the flying lobsters.

When we learn that Wanda is directly responsible for the role she has chosen for herself, as well as for “casting” all the Westview residents in their respective roles, the “Bewitched” comparison no longer holds. And we see that the casting of Agnes/Agatha as the “nosy neighbor” role was a feint, a way for the witch Agatha to infiltrate Wanda’s world and tweak it a bit (it was “Agatha all along!”), all while observing Wanda’s magic.

What Stage of Grief is This?

In the penultimate episode, “Previously On,” we see that these sitcom homages aren’t just clever meta references that the showrunners, including creator Jac Schaeffer, want to reference, but they are actual in-universe memories that Wanda had of escapist entertainment as a child growing up in war-torn Sokovia. This is the episode where we see Wanda’s painful and traumatic experiences, although oddly enough for a show about meta-performance, we watch Wanda and Agatha watching them.

It is this episode we get the flashback with the Vision, in the aftermath of Pietro’s death in “The Age of Ultron,” comforting Wanda and uttering the perfect line, “what is grief if not love persevering.” We see that Wanda’s escapism into American sitcoms is borne of her extreme trauma, grief and PTSD.

As audiences, dealing with collective trauma and grief over a year of quarantine and 530,000 deaths, we deeply relate and acknowledge how simple acts like binge watching television can be a balm in an otherwise cruel world. We sympathize with Wanda wanting to escape into a television world where conflicts are resolved at the end of the half hour, where communities remain intact despite conflicts. We gladly lose ourselves in the nostalgia and meta-references that the WandaVision showrunners have created because we feel similarly inspired by classic television (or at least that’s the audience empathy that the showrunners counted on).

And yet…

Early on, we accept the structure of the sitcom setting for the first few episodes, though I’m sure many viewers were confused. Even after we learn that Wanda is controlling things and broadcasting her “show” we watch with glee along with Darcy and Jimmy. But yet, the show never explains why there is a “broadcast” at all. If Wanda wants to escape into the perfect world depicted in sitcoms, why doesn’t she just imagine those worlds as real? Why does she create the conventions of sitcoms, with audiences, canned laughter, and then later, directly acknowledging the camera, and breaking the fourth wall (actually the name of episode seven)?

Wanda even creates commercials, presumably a manifestation of her subconscious, that name check Stark Industries, Hydra, and other aspects of her comic and MCU history. The final “commercial” is particularly telling. In what many have suspected is a reference to the “nexus of all realities” in Marvel Comics, the ad promotes an anti-depressant called “Nexus,” in parody of typical drug ads: “ask your doctor about Nexus, because the world doesn’t revolve around you. Or does it?”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NKEFG7B0nIo

My performance studies scholar identity reels at the possibilities here. Wanda doesn’t just create a fantasy world. She creates an elaborate performance that can be watched. She makes sure it’s a fantasy world that imposes her will entirely on the Westview town, and then makes sure that the fantasy world is viewable from the outside. It’s never clear how much Wanda intentionally makes any of this happen or whether it’s just an odd side effect.

Perhaps this is what Agatha means when she accuses Wanda of performing “chaos magic,” affirming she is the “Scarlet Witch” mentioned in the Darkhold book (up until that point in the MCU, she didn’t have a superhero name, which Darcy reminds us of when she first appears). I could write a whole other article on the intersection of chaos magic in pop culture, and its particular association with nostalgia and the media, in everything from Sabrina (sometimes known by the acronym CAOS, for Chilling Adventures of Sabrina) to the comics of Grant Morrison. As well as the ways that WandaVision itself created its own chaos which inspired endless theorizing by viewers, much of which were proved to be completely red herrings.

Suffice it to say, there are no rules for Wanda and her power seems practically unlimited. In the final episode, “The Series Finale,” we get the long awaited superhero battles, including the reconstructed Vision without a memory or conscience (the “white Vision”) vs Wanda’s reconstructed but still independently thinking hex Vision (which is fascinatingly resolved in a Ship of Theseus debate).

And we also get a midair sky battle between Wanda and Agatha, done up finally in an over the top witch costume and makeup. We even get a hit-you-over-the-head “Wizard of Oz” reference when Wanda throws a car at Agatha and we see her feet sticking out in a crushed house. Clearly, this is a battle between the classic Hollywood witch trope and the more contemporary empowered but off-kilter superheroine with magickal powers.

But in the midst of the battle, we get a crucial scene. Agatha releases the townspeople from Wanda’s spell and as they become conscious, they surround Wanda, pleading with her to reunite them with their partners and children. Sitcom queen Debra Jo Rupp’s character, horrifyingly, even begs to be killed in order to be permanently released from Wanda’s influence. Another character tells Wanda that they dream her nightmares. The townspeople literally say “your grief is poisoning us!” One would be forgiven for thinking that Agatha is the hero for actually saving the townsfolk and Wanda is the villain.

Angels to Some, Demons to Others

And that’s the question. In the comics, Wanda goes back and forth from hero to villain with regularity. But here, the effect of Wanda’s powers is depicted rather realistically. She has terrorized the townspeople of Westview. After Agatha has been defeated and Wanda decides to undo her spell, she walks away as they all glare at her in contempt. And while Wanda vehemently denies Agatha’s accusation that she’s a witch, I half expected the townsfolk to point their fingers and accuse her themselves. She acknowledges that they hate her, but still walks away without a thought for recompense or in any way making up for what she has done.

And oddly enough, we get Monica Rambeau, the closest we have to an audience surrogate on the show, and now a superhero herself because of Wanda’s powers, empathizing with Wanda, saying “they don’t know what you gave up for them!” Monica has her own struggles with grief, waking up from the blip in “Avengers: Endgame” to learn that her mother had succumbed to cancer during her absence.

But here’s where I started to wonder. We tend to hold up superheroes in our culture as answerable to a higher law and moral standard, to in fact be above the law, quite literally. Since their inception in the 1930s, critics of the superhero genre have associated its characters with a certain kind of fascism, and recent works, such as “The Boys,” have hammered that point home.

At the end of the show in the mid-credit sequence, we see that Wanda has gone to a cabin retreat, perhaps to recover and actually confront the grief that she denied before the series started. But we find that her astral form, dressed as her fully realized Scarlet Witch identity, has doubled down on the dark magick and is studying the aforementioned “Book of the Damned,” the Darkhold. The image of Wanda’s bifurcated self both being at peace and indulging in chaotic power is a troubling one.

Superheroes, especially in the MCU, are a troubled bunch. It’s too bad that Leonard Samson (played by Modern Family’s Ty Burrell) was such a throwaway character in “The Incredible Hulk” back in 2008. In the comics, Samson, powered by a certain amount of Hulk-inspired gamma energy, is actually a therapist for the Marvel superheroes. One of the more well known appearances of Samson was when he therapized the X-Men spin-off, X-Factor, including Quicksilver, Wanda’s brother.

The MCU heroes definitely need some serious therapy (note: after I first posted this, the premiere of the next Disney + show, “The Falcon and the Winter Soldier” actually showed Bucky…in therapy!). Yet we forgive them their trespasses. We’re meant to feel sympathy for Wanda in dealing with her grief. Articles, like this one, inspired by the “grief is love persevering” sentiment in the show have been popular and others have used the show to talk about the five stages of grief.

Narcissism and Superheroes

But what about those severely traumatized Westview residents? We usually don’t see the fallout from the superhero adventures, other than brief scenes such as the confrontation between Alfre Woodard’s character and Tony Stark in “Captain America: Civil War.”

But the depiction of Wanda and her actions in WandaVision begs the question, are superheroes just giant narcissists? Watching Wanda Maximoff casually manipulating a whole town I couldn’t help but think of toxic people who draw others (sometimes innocent bystanders) into their dramas, who gaslight and impose their inner life and often warped perspective on others, who project their unresolved and unaddressed feelings and abusive behaviors onto others.

Again, usually it’s the villain who does this, such as Father Blackwood on “The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina.” Or a certain former President who attempted to create a different reality in which he won the election (and still tries!).

Wanda not only manipulates the town, but creates a clever program for others to watch her do it! Are we not entertained?

Now, don’t get me wrong. I grew up on Marvel. I love the MCU and I think the characters are fantastic adaptations of their comic counterparts for the most part. But I wonder just how much we excuse, in fact, celebrate, awful behavior even in our fictional characters. I was struck by a recent piece in Vox, that addresses this very question, discussing “story karma” in relation to WandaVision. While again, as a rabid MCU fan, I found myself a bit more forgiving than the author, her point that WandaVision doesn’t follow through on the culpability of its main character is well taken:

“What many WandaVision viewers are waiting for is…that reassurance from the show’s storytellers that they know what she did was just that awful. In that case, Wanda could get away with far worse, and we’d all breathe easier, knowing that somebody somewhere had their eye on the scales of justice.”

Perhaps those consequences will be seen in Wanda’s next MCU appearance, the Doctor Strange sequel, that is still a year away. But somehow I doubt it. And that leaves us to determine if we can see ourselves superior to Wanda, and actually discern between television and reality.

Final note: I watched WandaVision with my teenage daughter and she’s an avid Wanda fan and aspiring editor and created this fantastic video of scenes from Wanda’s appearances in the MCU! Enjoy!