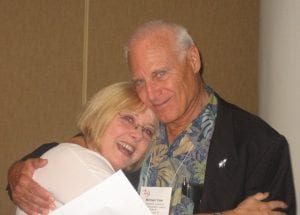

Last week, the world of academic Pagan Studies lost a giant. Scholar, author, researcher, and drummer Wendy Griffin passed away at the age of 78 on February 12th. Her death was deeply affecting to me and to many others who knew her, were influenced by her or supported by her as she strove to legitimize the academic study of Paganism.

While I am ridiculously unqualified to offer tribute, I did encounter Wendy and work often throughout my career. She was an ongoing presence in the Pagan academic circles I frequented for many years, and I got a strong sense of who she was personally and professionally. And given the pedigree of this site, I think many of us, academic and non-academics alike, owe her debt of gratitude.

Pagan Studies

My first encounter with Wendy was through the Contemporary Pagan Studies focus group for the American Academy of Religions (AAR) convention. I was in the final stages of completing my dissertation and was presenting a paper on festival drumming at the 2006 AAR convention in Washington D.C. As a result of that presentation, I was recruited to turn the drumming paper into a fully realized chapter in the “Brill Handbook of Contemporary Paganism” anthology (2009).

At that conference, I was welcomed warmly and encouraged by the lovely folks of the Pagan Studies group, including many whose work I was already using in my scholarship, such as prominent academic Pagan authors Michael York, Helen Berger, J. Gordon Melton, Chas Clifton, Sarah Pike, Sabina Magliocco, Jone Salomonsen, the late Nikki Bado, and of course, Wendy, who was always at the center of every social activity. Always smiling and cheerful, and always ready for the post-panel dinner and drinks, the group very rightly gravitated around Wendy’s infectious energy, humor, and positive outlook.

Of course, by that late date, I was just stepping into what Wendy had helped establish some 25 years prior. Of the many tributes offered on Cherry Hill Seminary’s memorial page, Helen Berger describes Wendy’s tenacity at advocating for the serious study of Paganism within the broader academic field of Religious Studies. According to Berger, Wendy “knew how to organize, how to get things done, and how to make change happen.”

Even by the mid 2000s, to an AAR newbie, it was apparent that the struggle for legitimacy was ongoing. The more established focus group on Western Esotericism, where one would go for academic work on ceremonial magick and occultism, seemed to be overwhelmingly male and focused almost solely on historical and theoretical concerns.

In contrast, Contemporary Pagan Studies had a more vital feel, crossing over with anthropology, sociology, gender studies, queer studies, and ritual studies, among other fields. They focused on what people were actually doing now, rather than just what people did centuries ago. More importantly, rather than the openly displayed disdain for practitioners writing about their own work in the Western Esotericism group (despite the fact that those same concerns were never an issue in other areas about ordained priests writing about Christian practice), in the Pagan Studies group, writing from the position of practitioner/scholar was not only accepted but encouraged. I believe that was primarily because of Wendy and her efforts, as she was one of the first, if not the first, American scholar to openly identify as Pagan.

At the 2006 AAR, while certainly not everyone in the field was writing from the position of a practitioner, and debates over the effectiveness and impact of that positionality were active and lively, many younger scholars were beginning to feel more free to address their own personal practice and its role in their academic work. As a performance studies PhD candidate at Northwestern, I struggled myself to be taken seriously when I began to out myself as a Pagan and ceremonial magician in my coursework, school functions and conferences. So naturally, I was drawn to the academic community that Wendy had helped establish.

Researching Paganisms

One text particularly emblematic to these debates, published as part of the Pagan Studies series for Alta Mira Press that Wendy and Chas Clifton shepherded, was the anthology “Researching Paganisms” (2004), edited by Jenny Blain, Douglas Ezzy and Graham Harvey. The third chapter was an essay penned by Wendy herself, “The Deosil Dance,” in which she recounts not only the awful experience of losing her daughter during graduate school, but also her personal journey to address the notion of “objectivity” as she formed her scholarship on Goddess Spirituality while attending Dianic rituals and forming women’s drumming groups.

Wendy’s self-reflection on how she navigated drumming in ritual and social spaces was particularly influential to the work I did on my drumming and festival essay, as well as my own perceptions of my role as a participant/observer in ritual spaces where I drummed. Wendy’s willingness to engage with deeply personal experiences in conversation with scholarship, not only in terms of content but in methodology, was typical of the ethos that reverberated throughout Pagan Studies.

Even beyond Wendy’s contributions to Pagan Studies, which are indeed vast, the role she played in bringing change to the academy at large are also considerable, to the point where those developments in turn influenced popular notions of spirituality and women’s issues. For instance, she started one of the first Women’s Studies programs in the country, at California State College in Long Beach, which she eventually chaired, as the Department of Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies.

Wendy has a pretty amazing life story, which involved details like working in theatre Off Broadway with prominent actors, traveling as a gigging folk singer through Europe, devoting her time to being a leading activist for women’s issues, and being a published novelist.

Professionally, Wendy was also known for her involvement with the aforementioned Cherry Hill Seminary, where she served as their first permanent Academic Dean until her retirement in 2018. An online school before its time, Cherry Hill is a unique establishment focusing on Pagan theology and training. Wendy herself recruited me to teach for Cherry Hill, and I did propose courses. However, due to circumstances, including low enrollment, I never did teach any of them. Though caught up in some controversy and financial troubles in recent years, Cherry Hill remains one of the only educational centers for Pagan clergy.

Drumming and Identity

I didn’t know Wendy on a personal level all that well, but she was always very kind and encouraging to me. When I created a pre-conference at the 2012 AAR convention here in Chicago, called “Mapping The Occult City,” which consisted of international scholars, local leaders and practitioners, and DePaul students, Wendy attended the entire thing and actively engaged in the discussions and personally gave me feedback.

As I look back on my connection with Wendy, I keep coming back to her essay in “Researching Paganisms.” When I cited the essay in my own published work in 2009, I focused on her confessional statements about being a drummer and how drumming was still a way for her to “hide” in public spaces. She writes about drumming as a safety net of sorts, “whenever I felt that I was outside my comfort zone or being drawn in too far into emotions or self-revelation.”

Given that my scholarly agenda in my own essay was to present drumming as a potentially political act, representing a range of possible social interactions, I attempted to provide a contrast to Wendy’s views on performance as “safe.” While I didn’t necessarily disagree with her, I felt it important to note that her characterization was only one of many possible approaches. But ultimately, it’s one of those moments most academics will recognize where you find an authoritative voice that touches on certain topics, and use that voice as a jumping off point for your own claims.

Yet, here I am, almost a decade later, having effectively left academia, but continuing to drum at festivals, rituals and onstage (well, in the Before Times). As I’ve gotten older, and I’m more honest with myself about my social and public interactions, I realized that Wendy was absolutely right. I have often brought a drum to an event as a kind of social buffer, giving me a way to engage with the social activity, while at the same time distancing myself and maintaining a safe space.

I can’t help but think I’ll always be reminded of Wendy whenever I drum.

Our Deosil Dance

At the end of her “Researching Paganisms” essay, Wendy concludes “Who we are, where we have been, and how we go about our research all contribute to shaping both our understanding of the spiritual practice and the practice itself. Knowing this, I cannot help but wonder what Paganism will look like tomorrow and if the next generation of researchers in Pagan studies will be looking at the results of our deosil dance.”

I think of women like Margot Adler, Nikki Bado, and Patricia Monaghan, my late friend and colleague from DePaul, and the ways that their work and their dances reverberate still in the Pagan and academic worlds.

Not only have Pagan academics looked to what those like Wendy have created and danced, but I’d venture to say that most of the Pagan writers on this very website, a religiously oriented site run by a Christian organization, have learned and benefited from that work, even if they don’t necessarily realize it.

May we continue to honor Her work.

What is remembered, lives.

Post-script – While my experience with Dr. Griffin was minimal and at somewhat of a distance, I do want to acknowledge that there has been some significant discussion amongst my Pagan Studies colleagues about her problematic legacy, particularly with regards to transphobic views and policies that she actively supported (as suggested by the controversy I linked in the article). While I’m hoping others with more direct knowledge and experience do continue to address those issues in the future, I did not feel I had enough exposure to that side of Wendy’s career and relationships to comment effectively. As with so many things nowadays, we must be clear-eyed about the multiple sides to the artists and scholars we revere.