I was nine years old and in fourth grade the Christmas Eve Santa Claus visited my brothers and I in the flesh. Nine is the age when most kids have stopped believing in Santa Claus but haven’t necessarily admitted it to their parents yet, so when Santa made his visit I was pretty dubious. He came in through the front door with a bag slung over his shoulder and he gave all four of us boys the toy type present we were interested in at the time. My brothers were into match-box cars and they each got a set that suited them perfectly. I liked those little green army men back then, but Santa did one better, he got me a set of army men with Japanese soldiers, the holy grail of hard to find two inch plastic toys. Completely mind blowing.

I was nine years old and in fourth grade the Christmas Eve Santa Claus visited my brothers and I in the flesh. Nine is the age when most kids have stopped believing in Santa Claus but haven’t necessarily admitted it to their parents yet, so when Santa made his visit I was pretty dubious. He came in through the front door with a bag slung over his shoulder and he gave all four of us boys the toy type present we were interested in at the time. My brothers were into match-box cars and they each got a set that suited them perfectly. I liked those little green army men back then, but Santa did one better, he got me a set of army men with Japanese soldiers, the holy grail of hard to find two inch plastic toys. Completely mind blowing.

I spent the rest of the night trying to figure which adult in my family had dressed up as Santa Claus, but they were all in the back-room when he made his entrance. It had to be someone who was familiar with us because he knew all of our names, but I couldn’t come up with any probable candidates. We were also a hundred miles away from home at my Grandparents’ house, so it wasn’t a neighbor. It was a Christmas Eve mystery, and one I’ve never solved. The next year I asked my Dad about the Santa incident who replied that he had no idea who our visitor was, and that his parents didn’t know either. Over the succeeding years I continued to ask the question, and always got the same reply.

Deep down I know that we weren’t visited by a citizen of the North Pole that evening, but the mystery of it all makes it special. It’s a magical memory, the exact type of thing that the image and myth of Santa Claus should conjure up. Santa Claus has power and an energy all his own. To say that Santa “isn’t real” completely misses the point. Few myths are as universal in the Western World as that of Midwinter gift-bringer, and it’s a myth that speaks to the best of who we can be as people. Santa is the spirit of giving and child-like wonder, two impulses that are often in short supply.

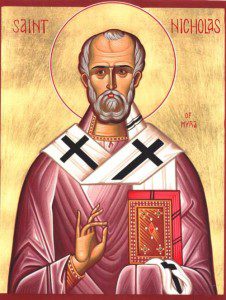

Any serious discussion on the origins of Santa Claus has to begin with Saint Nicholas, even though it’s difficult to know exactly just where to begin. Just like Santa Claus the story of Nicholas is myth; there’s just not enough evidence to say with any certainty whether or not Nicholas actually existed. According to legend Nicholas was the Bishop of Myra (a coastal town in present day Turkey) and was active in the early Fourth Century. He allegedly died on December 6, in the year 343 CE, which later became his feast day.

Any serious discussion on the origins of Santa Claus has to begin with Saint Nicholas, even though it’s difficult to know exactly just where to begin. Just like Santa Claus the story of Nicholas is myth; there’s just not enough evidence to say with any certainty whether or not Nicholas actually existed. According to legend Nicholas was the Bishop of Myra (a coastal town in present day Turkey) and was active in the early Fourth Century. He allegedly died on December 6, in the year 343 CE, which later became his feast day.

Over the ensuing centuries all sorts of miraculous stories began to circulate involving Nicholas. He fed the hungry, calmed oceans, and gave generously to those in need. Many of the Nicholas stories are so ridiculously over the top that they read more like comic-books than events with any basis in reality. Nicholas was apparently capable of flight and was able to teleport; appearing suddenly out of thin air to confront individuals about their misdeeds.

The most famous of the Nicholas stories involves a poor old widower unable to provide a dowry for his daughters, condemning them to a probable life of spinsterhood. Upon hearing of the old man’s plight Nicholas anonymously tossed bags of gold into stockings hanging in the man’s house over three consecutive nights. Nicholas’s act allowed the widower to provide a dowry and the girls were subsequently wed and lived happily ever after. In early versions of this tale Nicholas provides dowries, but the socks are absent, most definitely a later addition to line up more favorably with the later myths of Nicholas as gift giver.

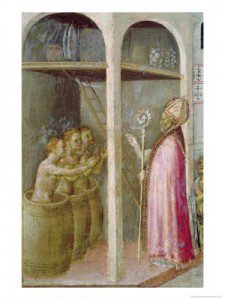

Nicholas also had the ability to overcome death. One of the most famous of his myths involves a murderous inn-keeper and the murders of three university students. Upon entering the establishment of the evil inn-keeper Nicholas immediately sensed that something horrible had happened. He strode into the inn’s cellar and found the corpses of the murdered boys in a pickling barrel, and then promptly resurrected them from the dead. Instead of condemning the inn-keeper Nicholas forgave the man and even blessed his barren wife with the ability to produce offspring. Stories of Nicholas’s miraculous powers, love of children, and ability to forgive made him the favored Saint in much of Europe, and by the year 1100 he had become the most revered Saint in the Catholic Church. (It didn’t hurt that by 1100 Nicholas was the patron Saint of almost everything.)

Nicholas also had the ability to overcome death. One of the most famous of his myths involves a murderous inn-keeper and the murders of three university students. Upon entering the establishment of the evil inn-keeper Nicholas immediately sensed that something horrible had happened. He strode into the inn’s cellar and found the corpses of the murdered boys in a pickling barrel, and then promptly resurrected them from the dead. Instead of condemning the inn-keeper Nicholas forgave the man and even blessed his barren wife with the ability to produce offspring. Stories of Nicholas’s miraculous powers, love of children, and ability to forgive made him the favored Saint in much of Europe, and by the year 1100 he had become the most revered Saint in the Catholic Church. (It didn’t hurt that by 1100 Nicholas was the patron Saint of almost everything.)

Nicholas was also renowned as the patron Saint of sailors. Stories tell of Nicholas saving the lives of sailors “perishing at sea” while also being involved in the deliberations happening at the First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE. The stories of Nicholas at sea are interesting because it’s been speculated that at least some of his myth was borrowed from pagan sea-gods, most specifically the Greek Poseidon. In fact, one of Nicholas’s earliest cathedrals was built on the site of a temple dedicated to Poseidon and several other places dedicated to Nicholas are near those once reserved for the Greek god of the sea.

One of the most interesting things about the Nicholas myth is that the Saint simply died of old age. He did not die a martyr, nor are any stories of martyrdom associated with the old Bishop. How much this factored in the popularity of his cult is an open question. Instead of a grisly end, it’s the stories of Nicholas’s generosity and good-nature that are remembered.

Whatever the origins of Nicholas’s myths his popularity in Medieval Europe was indisputable. He was even said to assist Muslims and Jews in their times of need (along with any other “unbelievers”). By the year 1100 French nuns were leaving gifts at the homes of poor children on the night of December 5 in the name of Saint Nicholas. Soon St. Nicholas would be doing the same thing in other places, but only after going through yet another re-imagining of his mythos.

Whatever the origins of Nicholas’s myths his popularity in Medieval Europe was indisputable. He was even said to assist Muslims and Jews in their times of need (along with any other “unbelievers”). By the year 1100 French nuns were leaving gifts at the homes of poor children on the night of December 5 in the name of Saint Nicholas. Soon St. Nicholas would be doing the same thing in other places, but only after going through yet another re-imagining of his mythos.

The legend of Nicholas is an important piece of the puzzle that eventually became Santa Claus, but it’s not the only one. The Santa Claus myth was affected to a large degree by a whole host of Norse myths and gods. The most influential of these are the Norse Odin and Germanic Woden (two similar deities that share a great deal of mythology). One of the most important holidays in Norse and Germanic paganisms was the celebration of Yule, the Winter Solstice. On that day Odin would lead the Wild Hunt, descending from the skies upon the back of a magical horse to punish the wicked. It’s from these myths that St. Nicholas would derive the white horse (Schimmel) he now rides in the Netherlands in order to give gifts. Odin’s horse was also capable of landing on rooftops, an important development. Odin was also a gift-giver like Nicholas, sharing his wisdom with mortals via the runes.

In 1980 a theory began to circulate that Santa Claus was a direct descendant of Siberian shamanism. According to this theory everything related to Santa can be found in Siberian shamanic tradition. In this hypothesis Santa flies like a shaman in a sleigh, reindeer are representative of Siberian reindeer spirits, and his red and white robes derive from the agaric mushrooms used to facilitate shamanic trance. In reality shamans never rode in sleighs, rarely contacted reindeer spirits, and only used mushrooms on very rare occasions. In addition, reindeer were a Nineteenth Century addition to the Santa-mythos and Siberians didn’t wear red and white clothes. In other words, if Santa is related to shamanism, it’s very indirectly. (See Ronald Hutton, Stations of the Sun, pages 117-119.)

In some parts of Scandinavia it’s possible that Thor was the more influential of the Norse gods. In those areas Nicholas would end up with a goat pulling his cart, or in the case of the Yule Goat, the goat would become the gift-giver. Like Odin, Thor was also capable of great generosity and was honored near the Winter Solstice.

In some parts of Scandinavia it’s possible that Thor was the more influential of the Norse gods. In those areas Nicholas would end up with a goat pulling his cart, or in the case of the Yule Goat, the goat would become the gift-giver. Like Odin, Thor was also capable of great generosity and was honored near the Winter Solstice.

Several other holiday gift givers would later influence the Santa Claus myth, with many of those “others” also coming from Scandinavian paganism and folklore. Until relatively recently no one ever characterized Saint Nicholas as “elvish” or small, but before Santa Claus there were several elvish and gnomish gift givers. Many of them bare far more similarities to early versions of Santa Claus than to the St. Nicholas myth. It’s possible that remembrances of gift-givers like the Tomte led to not only Saint Nicholas/Santa being an elf but to the big-man having an elven workforce.

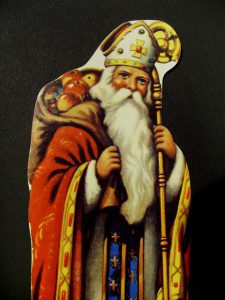

During the Reformation, Protestants tried in vain to cease the veneration of Saints, especially Saint Nicholas. Reformers suggested switching Saint Nicholas with the Christ Child (Baby Jesus) and leaving gifts on Christmas instead of the Feast Day of Nicholas. Their efforts had some success in Eastern Europe and Germany, less so in the Netherlands where children led protests demanding the reinstatement of Nicholas as gift-giver. Nicholas won. (Eventually the Christ Child became the Christkindl and evolved from baby Jesus into an angelic figure, generally portrayed by a young woman. In English Christkindl was often pronounced Kris Kringle and led to another name for Santa Claus.)

It’s logical to assume that the Dutch colonists who settled in North America brought their tradition of Sinterklaas with them (a Dutch term for Saint Nicholas, who is also sometimes known as Sint Nicolaas in the Netherlands) but remarkably, there’s little to evidence to back up that claim. The first mention of Saint Nicholas as magical gift giver in what would become the United States dates back to 1773 when the New York newspaper Rivingston’s Gazatteer makes mention of Saint Nicholas “otherwise called St. a Claus.” It’s likely that several Dutch families maintained the cult of Nicholas, but it’s impossible to say with absolute certainty.

What is known is how interest in Sinterklaas reawakened in the Nineteenth Century, and how it quickly spread everywhere in just a few decades. In 1809 Washington Irving released A History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker with references to Saint Nicholas as New York’s patron Saint and guardian along with stories of him delivering presents and sliding down chimneys. Irving was a New Yorker, but he wasn’t Dutch, and his history was meant as satire, but people responded to his imagined reminisces and interest in Nicholas was revived. In 1810 a poem about the gift-giver appeared in the New York Spectator, complete with the line “Oh good holy man! whom we Sancte Claus name.” Santa Claus was in business.

In 1821 an uncredited poem appeared in a small book entitled The Children’s Friend: A New Year’s Present, to Little Ones From Five to Twelve. It’s one of the most important poems in all of Santa history, though mostly forgotten today. Not only does it establish “Santeclaus” as a magical Christmas gift-giver, but it also marks the first recorded instance of Santa having reindeer. (Until 1821 Santa still generally travelled by horse.) The picture of Santa painted in The Children’s Friend is far more stern than our modern Santa, but it’s recognizable. The pictures that accompany the poem show a very Saintly looking Santa, though he is wearing red. (You could buy a hand-colored edition of the The Children’s Friend at extra cost.)

Old Santeclaus with much delight

His reindeer drives this frosty night,

O’er chimney-tops, and tracks of snow,

To bring his yearly gifts to you.The steady friend of virtuous youth,

The friend of duty, and of truth,

Each Christmas eve he joys to come

Where love and peace have made their home.Through many houses he has been,

And various beds and stockings seen;

Some, white as snow, and neatly mended,

Others, that seemed for pigs intended.Where e’er I found good girls or boys,

That hated quarrels, strife and noise,

I left an apple, or a tart,

Or wooden gun, or painted cart.To some I gave a pretty doll,

To some a peg-top, or a ball;

No crackers, cannons, squibs, or rockets,

To blow their eyes up, or their pockets.No drums to stun their Mother’s ear,

Nor swords to make their sisters fear;

But pretty books to store their mind

With knowledge of each various kind.But where I found the children naughty,

In manners rude, in temper haughty,

Thankless to parents, liars, swearers,

Boxers, or cheats, or base tale-bearers,I left a long, black, birchen rod,

Such as the dread command of God

Directs a Parent’s hand to use

When virtue’s path his sons refuse.

The most important poem ever written about Santa Claus was first published in 1823. Though there is some dispute over the authorship, most people attribute An Account of a Visit From St. Nicholas (The Night Before Christmas) to Clement C. Moore who originally wrote the poem for his children. The following year it was reprinted without his permission and in 1844 Moore made his first public claims of authorship. Once his claim to authorship became public knowledge he tweaked the poem in several places, most notably changing the names of the reindeer formally known as Dunder and Blixem.

The most important poem ever written about Santa Claus was first published in 1823. Though there is some dispute over the authorship, most people attribute An Account of a Visit From St. Nicholas (The Night Before Christmas) to Clement C. Moore who originally wrote the poem for his children. The following year it was reprinted without his permission and in 1844 Moore made his first public claims of authorship. Once his claim to authorship became public knowledge he tweaked the poem in several places, most notably changing the names of the reindeer formally known as Dunder and Blixem.

Santa is instantly recognizable in The Night Before Christmas, yet a closer reading of the poem indicates that the stately figures of Odin and Saint Nicholas have been completely revised. Santa is now a “right jolly old elf” and with a belly like “a bowlful of jelly.” His clothing had changed too. No longer was in he robes, now he was “dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot, And his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot.” Santa’s reindeer have also multiplied since 1821, and due to the influence of Moore’s poem “eight” (nine with Rudolph) has become the agreed upon number of sleigh pullers. Even if Santa doesn’t look quite right in Christmas it contains all the other essential Santa elements.

While Moore’s Santa became the accepted version after the publication of his poem, several alternate versions of the character persisted over the next few decades. Some writers took the “elf” idea a little too far and made Santa the size of a mouse. Other variants on the character had him riding a broomstick instead of driving a sleigh, there was even a clean-shaven Santa with a turban on top of his head. An African-American representation of Santa also existed, forever putting to bed the stupid theory that “Santa is just white.” Santa was all kinds of things, but the image that resonated most involved a little driver, lively and quick.

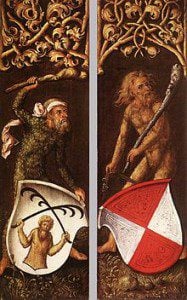

For most Americans it would be the Bavarian-born Thomas Nast who would forever define Santa Claus. Nast’s Santa was much like Moore’s, but a short man instead of a jolly elf, and most likely influenced by the customs of his homeland. Nast didn’t look for his Santa in the images of Saint Nicholas, he found them in the European folk traditions of characters like the Belsnickel (German for Nicholas in Furs). His Santa looked similar to the Wild Men of legend in Europe (essentially boogie-men living outside of society), but less scary. His Santa Claus wasn’t a bishop but a man of the people.

For most Americans it would be the Bavarian-born Thomas Nast who would forever define Santa Claus. Nast’s Santa was much like Moore’s, but a short man instead of a jolly elf, and most likely influenced by the customs of his homeland. Nast didn’t look for his Santa in the images of Saint Nicholas, he found them in the European folk traditions of characters like the Belsnickel (German for Nicholas in Furs). His Santa looked similar to the Wild Men of legend in Europe (essentially boogie-men living outside of society), but less scary. His Santa Claus wasn’t a bishop but a man of the people.

Nast built upon the Santa Claus being established by other writers and illustrator. In Nast’s illustrations Santa was seen living at the North Pole (one cartoon even lists it as his proper address). He also established the tradition that Santa knows “when you’ve been bad or good.” Nast also showed Santa getting mail from children listing their yearly wants.

Nast built upon the Santa Claus being established by other writers and illustrator. In Nast’s illustrations Santa was seen living at the North Pole (one cartoon even lists it as his proper address). He also established the tradition that Santa knows “when you’ve been bad or good.” Nast also showed Santa getting mail from children listing their yearly wants.

When Nast’s Santa Claus drawings were reprinted in magazines the furs he drew in black and white were often colored red. By the 1850’s the red and white suit was already Santa’s most popular outfit, and when Nast’s drawings appeared in color the same way it cemented the deal. It’s cute to think that Coca-Cola had some sort of input on the design of Santa’s suit, but they were simply going along with what was already popular.

The famous Coke adds depicting Santa that began in the 1930’s were the work of Haddon Sundblom, and they did help contribute to the Santa Claus mythos. Sundblom made his Santa taller than Nast’s, and that increased height for Santa increasingly became the standard. Sundblom’s Santa also lacks the ocassional rough edges Nast gave to his versions of the character. When you look at Sundblom’s illustrations it’s clear that Santa belongs in every house on Christmas Eve, it would be hard to mistake this Santa for a burglar or vagrant. Sundblom’s vision of Santa became the standard image of the gift-bringer, and remains so nearly eighty years later.

The famous Coke adds depicting Santa that began in the 1930’s were the work of Haddon Sundblom, and they did help contribute to the Santa Claus mythos. Sundblom made his Santa taller than Nast’s, and that increased height for Santa increasingly became the standard. Sundblom’s Santa also lacks the ocassional rough edges Nast gave to his versions of the character. When you look at Sundblom’s illustrations it’s clear that Santa belongs in every house on Christmas Eve, it would be hard to mistake this Santa for a burglar or vagrant. Sundblom’s vision of Santa became the standard image of the gift-bringer, and remains so nearly eighty years later.

Santa’s had a long and bumpy road on his way to becoming a modern icon, but now that he’s here he doesn’t look likely to leave anytime soon. In a world that so often lacks any magic, Santa provides a doorway into a realm of imagination and wonderment. A world without Santa is a world I don’t want to live in. We share so little myth these days, and what myth we do share rarely transcends religious boundaries, but Santa is different. With his origins in Greek myth, Catholic tradition, Norse paganism, and the wilds of the human imagination, he’s capable of not just magically jumping down chimneys, but of jumping into the hearts of whoever will have him.

A Santa Bibliography

Santa Claus: A Biography by Gerry Bowler. McClelland & Stewart, 1997. There’s a lot to like here. His history of Saint Nicholas is thorough and the look at Santa’s first 100 years is pretty thorough. Sadly, Bowler dismisses any pagan connections to Santa Claus with a footnote directing interested readers to other sources.

Stations of the Sun by Ronald Hutton. Oxford University Press, 1996. Hutton’s book is dedicated to the history of the ritual year in Great Britain, as a result his treatment of Santa Claus only gets a few pages, but they are insightful few pages.

Santa Claus, Last of the Wild Men: The Origins and Evolution of Saint Nicholas, Spanning 50,000 Years by Phyllis Siefker. McFarland and Company, 2006. I don’t buy into any origin story of Santa dating back to pre-history, the gaps in the historical record are just too large. That being said, this is still an interesting take on the Santa mythos and I believe it has some merit.

When Santa Was a Shaman by Tony van Renterghem. Llewellyn Publications, 1995. I just got through re-reading this book, it’s an experience I don’t ever want to repeat. There’s some information here, but mostly bad history. Any book that attempts to equate the gods Herne and Pan is not going to sit well with me. There are some nice pictures.