I have been a devotee of the god Shiva for nearly fifteen years. While my experiences with Him haven’t quite been as dramatic as those with Pan, Dionysus, or Cernunnos; he still holds a place in my heart. On an emotional level I feel as if I understand Shiva, on an intellectual level when reading about Him I sometimes feel as if I’m reading about dozens of different deities that all just happen to have the same name.

Writing about Shiva presents a multitude of challenges for a variety of reasons. The worship of Shiva is a very real, continuing thing, and has been for over 3000 years. I worship several gods that have been a part of the historical record for at least that long, but they all have long gaps in their worship. Shiva’s worship has been constant, and he’s not a god re-emerging in the Modern World, he’s been an active part of things since he was first worshipped. Gods like Pan have been reconstructed to some degree to fit the modern age, Shiva has just always been. Any “tinkering” has been done on the fly.

There is also a large cultural gap that has to be bridged when writing about Shiva. Shiva is an Indian god, and his myth and worship have elements that are extremely alien to most of us in the West. In addition to that, Shiva’s worship generally falls into the category of “Hinduism,” which is in its self a terrible and misleading term. There is no one Hindu religion, there are hundreds of traditions in India lumped under the word.

The idea that “All gods are one” is a very real one in India, and also contributes to the difficulties that arise when one writes about Shiva. In Hindu tradition Shiva is said to have “1008 names,” which means that Shiva has appeared in various roles over the millennia, and in each role attributed to Shiva, a different name gets attached to Him. To further complicate matters, one aspect of Shiva might be vastly different from another one. Sometimes the only thing linking “two Shivas” is tradition. If a deity is traditionally thought of as Shiva, he is Shiva, regardless of how well that idea fits within the other aspects of the god.

While most of you out there have probably heard of Shiva, there is some debate over whether or not that is really even his name. Most anthropologists and religious historians spell his name “Siva” today, as most of the “h’s” have begun to be removed from the Western spellings of Indian names. This brings them closer to the actual Indian pronunciation, but can be kind of confusing if it’s not explained to you. I continue to use the word Shiva because it’s how I know Him, and He seems to always respond to it. It’s also the name most other people know the god by. (For another perspective on Shiva from a Modern Pagan be sure to read Shiva the Witch God by Niki Whiting.)

This essay is not meant to paint a complete portrait of Shiva; instead it focuses on the attributes and aspects of His worship that I feel might most interest Modern Western Pagans. This might not be a completely honest approach, but it this is already a 4000 word article, it’s recommended that our pieces here run at 500 words. And instead of using his “1008 names” I generally use the term Shiva when describing any and all aspects of the god. I chose that method because it was less confusing, and also because it’s the one name of his that I use in my own personal practice.

I originally wrote this bit on Shiva for a book on the Horned God and during that process I tried hard to respect the traditions and culture(s) that Shiva arose from. Shiva certainly belongs to India and the people that cherish him so greatly, but I’ve been lucky enough to be blessed with His light in my own life. This bit only truly represents my take on the god, and my experiences with Him; as a result my interpretation of the god might be a lot different from some of his other followers.

I often feel like my love for Shiva exists “in the broom closest” so to speak. I don’t invoke Him in circle and I’ve never lead a public ritual in His honor. He’s an Eastern god, and I feel strange about brining him into my Western style worship. My time with Shiva is something that happens in private, but I sometimes feel that the Shiva I know wants to be introduced to a wider audience. At the heart of it, Shiva is a phallic and horned god, and a popular one at that. He doesn’t need me to introduce Him to a wider audience; he’s on plenty of Contemporary Pagan altars and the like, but if by sharing this someone draws closer to Him alls the good.

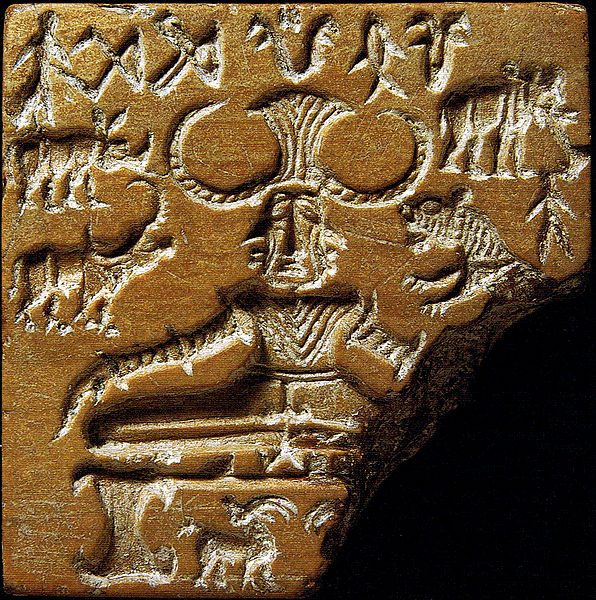

Shiva is an ancient god, though how old is a matter of debate. The oldest representation of Shiva dates back to the Indus River Valley Civilization in 3000 BCE. (The Indus River Valley Civilization was one of the first truly great cultures in the world. The Indus River Valley is a part of a modern day Pakistan, but its influence on the current nation of India was immense.) An image found there depicts a man sitting cross-legged with horns on top of his head. The figure is surrounded by horned (and tusked) animals, including bulls, deer, and elephants. The horns on top of his head are curved, and seem to suggest a crescent moon, a symbol that often adorns modern representations of Shiva.

There is a great deal of scholarly debate about this figure. Many are convinced it represents an early version of Shiva, or a proto-Shiva. Others suggest that it’s simply a man with a horned helmet on, or perhaps a strange depiction of an actual bull. The image also looks remarkably like those of seated bulls from the same time period. As with anything having to deal with ancient, ancient, history the jury is still out on this first depiction of (possibly) Shiva.

Judging from the animals around the image I think it’s pretty safe to say that it’s a god of some sort. The human-like figure is bigger than the animals he is pictured with and he dominates the scene. The Shiva-figure is clearly shown to be in a position of power, which makes a good case for the godhood argument. What strikes me the most about this early depiction of Shiva is how much he looks like other Horned Gods, especially Cernunnos. (This is most certainly a coincidence as Cernunnos doesn’t show up in the archeological record for nearly 3,000 more years, but it’s still interesting.)

One other criticism of the picture in regards to its likelihood of being an early image of Shiva is that it’s from the Indus River Valley Civilization. Most Indian history and culture is Aryan, as are most Hindu deities. However, since most deities in Hinduism are simply one part of a greater whole, it’s possible that this 3000-year-old figure is one of the first representations of Shiva, even if he wasn’t called that specifically.

I have always associated Shiva with the phallus, but in some traditions he is seen as an ascetic. Shiva has millions of followers who have renounced almost every pleasure in life in order to get closer to Him. In modern India it is still common to see beggars smeared with the ashes of the dead, wearing only rags as a way to honor the god. Followers of these “renouncer” sects are usually vegetarians, abstain from all sex (even masturbation), and generally wander alone in search of Shiva.

It’s odd to me that a god I associate with sex and pleasure can inspire his followers to behave in ways that seem so alien to me, but the ascetic aspect Shiva is the result of a continually evolving deity, and most likely the cultural tastes of India’s conquerors. Muslims and Christians have both imposed some of their value systems on the people of India, value systems that see any honoring of a sexual organ as sinful and obscene. Early Shiva worship was undoubtedly phallic, but over the years that aspect of his character has been repressed in some traditions dedicated to Him.

The worship of the phallus alongside Shiva is as old as the god Himself. Representations of the phallus have been found in the remains of the original Indus River Valley Civilization, and all modern temples dedicated to Shiva contain some sort of “sacred phallus” image/statue within them. When people go to worship Shiva they don’t bow down to an idol or statue, they pray to a lingam, a sacred recreation of the male member. The lingam is the one common item present at all levels of Shiva’s worship. Even the ascetic followers of Shiva pray to the lingam, and they are common in homes across the Hindu world.

A lingam is generally made out of clay, but can be made out of anything. In Kashmir there is a six-foot tall lingam made out of ice that has became a sacred pilgrimage site for followers of Shiva the world over. There are many other giant lingams across the subcontinent that are equally honored, some that are hundreds if not thousands of years old. Many followers of Shiva honor a more natural lingam, perhaps a leaf from a tree standing upright in a base. Eggs, and egg shaped objects are also sometimes used to represent the lingam (which might give Easter an entirely different meaning.)

While the materials used to make lingam might differ from place to place and follower to follower, two elements always remain the same. The first is the representation of the phallus; something upright, straight and erect. Every lingam needs a grounding point, a place to arise from, and that base is generally known as a yoni, a representation of the sacred vulva where all life emerges. While the phallus aspect of the lingam is the most obvious, a lingam is really a symbolic representation of the two forces that create life, and I can’t think of anything more horned and horny than that!

This joining of male and female within the lingam is the probable origin of the male/female Shiva. It many depictions of the god he appears more as a she than a he. This asexual Shiva is the natural blending of the yoni with the erect portion of the lingam. To many devotes of Shiva the god is Everything in the entire universe, and since the universe is full of both male and female, it makes sense to represent the One who is everything as encompassing all genders.

(Just a little note here, but isn’t it amazing how many phallic deities have these overwhelmingly female edges to them? Not only Shiva in his asexual form, but Dionysus and Kokopelli too. Our modern world seems to associate “being male” with violence and aggression, but some of the best male gods certainly represent a softer side of things. We’d be in a much better place as a society today if we ignored the screaming of the war gods like Yahweh, and focused more on gods like Shiva who transcend gender stereotypes.)

In modern day India the sexual aspect of the lingam is often downplayed, and tends to look more like a small nub coming up through a flat base than a glorious erection, but there is no denying the lingam’s origin. A lingam is seen as The God, and honoring it in the home (or temple) is equal to honoring the god Himself. People often decorate their lingams with flowers, anoint them with oil, and treat them better than they do their pets. It’s a very real and sacred connection to Shiva in all of his forms.

Lingams are not always made out of physical things; sometimes the lingam is honored as a pillar of fire. There is an old myth told about Shiva where he reveals himself to the other gods in the form of a large column of fire. This blazing wall of flame was so long as to have no visible beginning or end, and was seen as the source of all life by followers of the god. I like to think of it as a blazing phallic axis on which the world turns. As a result of that myth, many followers of Shiva associate fire with the god, and have a living flame upon their altar as a lingam.

Fire is also a great way to commune with Shiva. You can honor Shiva by offering him a sacrifice in whatever sacred fire you have going when performing ritual. I know what you are thinking; when we in the West think about sacrifices we often assume that means an animal sacrifice. While animal sacrifices are not uncommon in India, they are also rare. Most sacrifices involve putting cakes or liquor into the flame. The most sacred sacrifice in India contains no blood and is probably in your refrigerator, milk. The next time you call Shiva, sprinkle some milk into whatever flame you have going, He’ll appreciate it. (I’m curious as to what He might think about my wife’s almond milk . . . .)

There are many ways to honor Shiva in daily life. Some do it through sexual union and some devotes of the god do it through strict abstinence. For a long time this made absolutely no sense to me. How can you be a follower of Shiva praying to your lingam, and then not use your own lingam? I don’t think anyone can deny that sex is a very important part of our very being. Even when we aren’t having it, we focus on it. It’s a constant hum in the brain and between the legs, but what if it was possible to focus all of that energy elsewhere? Those who honor Shiva through abstinence aren’t denying their sexual natures, or even the sexual nature of the god, what they are doing is channeling the energy that would normally be used for sex and thinking about sex. If I could ignore my own sexual urges I would blog more. Abstaining from sex (and thoughts of sex) is a common tool in ceremonial magick too; it allows one to build up a stockpile of magickal energy that can be directed for whatever purpose. When a woman becomes so devoted to Shiva that she forsakes all others, she’s not forsaking passion in her life, she’s just focusing that passion on Shiva.

India is full of gurus devoted to Shiva who have forsaken sex in order to become closer to the god. While I’m not sure I could ever make such a commitment, I have engaged in sexual fasts before. With a little help from Shiva, you can keep the most carnal part of yourself quiet for a few days here and there. It’s not something I do it often, but there are times when I need to focus all of my energy on a certain project, and direct all of myself towards that goal. (The original draft of this piece took over a month to write, I needed much better focus back then.)

More than a fast; voluntary abstinence is magick. Magick is simply focusing energy on a particular goal, and focusing all of one’s simmering sexual energy on a specific thing is some pretty heavy-duty mojo. A god like Pan is going to allow one to get distracted, Shiva has a great deal of discipline when He wants too, and devotees of the god can use this to their advantage. The end of a great spell is almost like an orgasm too, all this crazy energy rushing out everywhere. When done right both orgasm and spell can be overwhelming and life altering. You don’t have to think of a period with no sex as a chapter of your life without cosmic release.

The most well known image of Shiva in the West is that of the cosmic dancer, the four armed Shiva dancing in a ring of fire. I think my first reaction to Dancing Shiva (this incarnation of Shiva is more accurately referred to as Nataraja) was one of fear and awe. Growing up I always associated this aspect of Shiva with destruction and saw within the swirling fire a Shiva intent upon destroying the world. This was probably the result of some bad comparative religion courses, but it was something that stuck with me for years.

Nataraja is certainly capable of destroying the world with His dance, and he’s been known to do so on a few occasions, but the dance of Shiva encompasses everything. While it certainly can be a dance of destruction, it’s more often a dance of joy. Honoring Dancing Shiva is to lose yourself in union with Him and ignore the outside world, much like dancing its self. Shiva is a god of dualities, and if something can be used to destroy, it can also be used to create.

When your life is built on the foundation of the Horned God it’s easy to lose your balance. You can either do everything in total excess, or cut yourself off from your passions in order to not let them get the best of you. Nataraja is the god of cosmic balance, and whom I look to when things get carried away one way or another. A great dance is a performance that hangs on the brink of anarchy. One misstep, can lead to disaster and the end of the dance. Dancing Shiva bridges the gap between living life to its fullest and falling victim to over-indulgence. Nataraja wants us to live life to its fullest, but to not over do things so that we go spiraling out of control.

Dance has been used in ritual and to achieve altered states of consciousness for thousands of years. (People have been dancing for at least 25,000 years or so, if we assume that they started dancing with the creation of drums and flutes, but people might have been doing it even before that!) Dancing to the sacred sound of the drum, which Nataraja-Shiva holds in his right hand, frees the mind from the pettiness of daily concerns. It allows for the individual to get swept up in Him.

In most depictions of Dancing Shiva the god is shown stomping on the demonic dwarf Muyalaka. Many interpretations have been offered as to why the Cosmic Shiva is nearly always shown with Muyalaka. Some think that Shiva’s trampling of the dwarf represents Shiva’s triumph over the individual’s ego. Some think that Muyalaka is put in the frame as a reminder that Shiva’s touch can reawaken the spirit of joy in even the most downtrodden individual, demonic dwarf or human being.

As a god with 1008 names Shiva has a whole host of holy days, but the best ones generally take place in the spring. The most important yearly festival honoring Shiva is Shivratri, which occurs during the first new moon after our Imbolc (so sometime in February or early March). Shivratri is the celebration of Shiva’s wedding day, so it has all kinds of sexual connotations (much like Beltaine in the West, it’s a rather fertile evening).

On Shivratri the lingam in the home is honored and given special care. It’s washed every three hours with milk, yogurt, or clarified butter and adorned with the leaves of apple trees. The homeless and poor are also honored, and giving generously to them is seen as a part of the holiday. Shivratri is said to be the day when Shiva makes himself most available to his followers. Sounds like a good night to honor Shiva in ritual to me.

Staying with the springtime fertility theme, Shiva is also honored on the next full moon after Shivratri. This holiday, called Holi, celebrates Shiva’s triumph over carnal desires and passion, even thought it features people leading processions with giant phalluses down city streets. It’s also a day full of sexual suggestion, as men often brag about their sexual prowess to the ladies on Holi. Holi is rather like a raucous carnival, and vistors to India are often told to stay in their hotels during Holi. In some areas it’s a day of crazy pranks, and I’ve read of excrement flying through the air on more than one occasion.

Since I have no desire to lead a celebration filled with flying poop, I tend to honor Shiva near the Wiccan holidays. I sometimes feel like it’s intellectually dishonest, but it feels right to me to worship him near Beltane and Ostara. As I mentioned earlier I don’t invite him to ritual, but before the festivities get underway I find time for Him.

For a phallic deity, Shiva seems to show a large degree of self-control. He can be worshipped in the form of a penis, yet abstain from sex. He doesn’t have the drinking problems of Dionysus or the urge to masturbate like Pan, but he’s not totally free from over-indulgence; Shiva loves hemp (marijuana).

People have been smoking marijuana in India for at least 6000 years, and Shiva’s association with the plant goes back at least 2000 years, maybe longer. Shiva’s cannabis indulgence is not an integral part of his mythology, but it’s around enough that you can’t help but notice it. Most references to it are in passing, and usually involve his wife Parvati nagging him about it.

In India, marijuana is considered to be a gift from the gods, and it’s thought to bring joy, courage, and sexual bliss to those who use it. While it’s certainly a part of Shiva’s existence, it’s not his entire existence, and that’s what separates one who enjoys a little bit of self-indulgence on occasion from a full blown addict. Shiva uses it to enhance his existence, not define it. Addiction is a terrible, very un-magickal thing, but being able to enjoy everything that this world has to offer, in moderation, is divine and magickal indeed.

The idea of enjoying all this world has to offer is the basis of the “tantric” tradition. Most of us in the west have heard of “Tantra” before, and usually associate it with sexual energy and the kama sutra. Such associations are not entirely accurate, as the tantric revelations involve all sorts of things, with sex simply being one small part of the whole. Tantric traditions are generally concerned with breaking down social barriers and challenging traditional morality.

In Tantric traditions women are given larger roles in ritual, and allowed divine secrets usually reserved for men. Caste and social barriers are flung aside, and peasant and noble are allowed to eat at the same table. Prohibitions against eating meat and drinking alcohol are ignored, and people engage in all sorts of sexual expression. For a long time in India religious figures taught that sex was strictly for the purpose of procreation. In tantra sex might lead to procreation, but it’s pleasurable attributes are also honored, and using every part of the body to receive and give that pleasure is encouraged.

Tantra arose to counter the growing ascetic nature of Indian religion during what we call the Middle Ages in the West. Tantra teaches that everything in the world is sacred, and that using all that this world gives us brings us closer to God (Shiva). Instead of looking at food as just a necessary act for our continued existence, tantra teaches that eating should be a joyful and pleasurable act unto its self. You can see where this is leading with regards to sex. The Tantric Shiva teaches that all pleasurable acts are sacred and lead to the divine.

While it’s hard to imagine a sometimes-ascetic god teaching that all acts of pleasure are divine, that’s the paradox this is Shiva. Shiva is everything to everyone. For many of His followers, Shiva is not just a god that they pray to-He is the universe! If Shiva is everything then it makes sense that both sex and abstinence would be a part of His existence. I think it’s very difficult for the Western Mind to reconcile all that is Shiva, but that’s what makes worshipping the god so much fun.