The Christian celebration of Easter has always been a good time to contemplate the nature of the gods and the relationships amongst the gods. As a Christian I was led to believe that the ministry of Jesus was a unique event in human history. To put it simply “Jesus was God made flesh,” and to have deity here on this planet as a human was a one-time only thing, never before written about or comprehended. Jesus-God was also able to overcome death, which becomes less shocking when your theology is essentially saying that Jesus is God, but as a kid that sounded pretty amazing.

In Paganism the idea that Jesus was simply one of many “dying and resurrecting gods” is an often repeated assertion. That particular idea has made its way into a large number of books over the years, and it’s often repeated ad nauseam on the internet, especially around Easter. In the 90’s I took that information as a gospel truth (sorry about the pun there), and found a lot of power in it. Like many Pagans I was searching for some sort of “validation” when it came to my new spirituality, Jesus as a brother/direct descendant of the gods of pagan antiquity worked as that validation.

The myth of the Dying and Resurrecting God is powerful, and it’s a myth I’ve used time and again in my own rituals. It speaks to my modern existence, and it works in my own cosmologies that revolve around The Wheel of the Year. It’s an effective metaphor at harvest time, and has been the source for several epic battles at the solstices. It also illustrates truths I believe about the gods; namely that the gods love the Earth and her children to such an extent that they would die to keep that Earth in balance.

If there’s a problem with the myth of the Dying and Resurrecting God it’s that the myth is essentially a modern one. The story of the Dying and Resurrecting God was best told in Sir James Frazer’s seminal work The Golden Bough, but the idea had been gaining steam for quite some time. Writing in 1875 Kersey Graves connected Jesus to several figures from pagan antiquity, and did it with such poetic grace that it’s hard not to buy into the whole theory:

If there’s a problem with the myth of the Dying and Resurrecting God it’s that the myth is essentially a modern one. The story of the Dying and Resurrecting God was best told in Sir James Frazer’s seminal work The Golden Bough, but the idea had been gaining steam for quite some time. Writing in 1875 Kersey Graves connected Jesus to several figures from pagan antiquity, and did it with such poetic grace that it’s hard not to buy into the whole theory:

“These have all received divine honors, have nearly all been worshiped as gods, or sons of Gods; were mostly incarnated as Christs, Saviors, Messiahs, or Mediators; not a few of them were reputedly born of virgins; some of them filling a character almost identical with that ascribed by the Christian’s Bible to Jesus Christ; many of them, like him, are reported to have been crucified; and all of them, taken together furnish a prototype and parallel for nearly every important incident and wonder inciting miracle, doctrine and precept recorded in the new Testament of the Christian’s Savior.”

The problem with the ideas both Graves’s, is that they aren’t an accurate depiction of history.

Pagan gods were never crucified (a Roman punishment for crimes against the state) and they were all conceived via sex. Sure, that sex was often miraculous, but it was sex. Hercules wasn’t born of a virgin, nor would I want him to be. I’m glad my gods were all having sex. Born of a virgin? No thank you, and you can take your oppression theology when you walk out the door.

Frazer wrote of gods that died in an annual cycle only to be reborn, but our pagan ancestors didn’t conceive of deity in such a way. Gods either die or return (think of Persephone, she certainly doesn’t die when she comes back to this world from the realm of the dead). In their individual myths they aren’t constantly dying only to be reborn or return from the dead. In The Encyclopedia of Religion historian Dr. Jonathan Z. Smith writes:

“The category of dying and rising gods, once a major topic in scholarly investigation, must be understood to have been largely a misnomer based on imaganitive reconstructions and exeedingly late or highly ambiguous texts . . .

All the deities that have been identified as belonging to the class of dying and rising deities can be subsumed under the two larger classes of disappearing deities or dying deities. In the first case the deities return but have not died; in the second case the gods die but do not return. There is no unambiguous instance in the history of religion of a dying and rising deity.” (1)

So if Jesus wasn’t a “dying and rising deity” in the alleged traditions of Adonis and Tammuz, what is his relationship to the deities of ancient paganism? When Christians argue that Jesus was unique among the gods of the Ancient World they are half right. There are certainly things about Jesus that are radically different from the pagan gods he is often associated with. On the other hand there are many things about Jesus which certainly have their origins with the pagan religions of antiquity. Even though Frazer was mostly wrong, he was right about one thing: without the pagan gods there would be no myth of Jesus the Christ.

Deity in the flesh. Pagan myth is full of gods that could be seen, touched, and heard. My favorite is Dionysus who spent a lot of time walking around the Mediterranean setting up grape fields and driving those who didn’t worship him literally mad. There are some myths that talk about the god even visiting ancient India. Dionysus and Heracles were both gods that “did stuff” in human bodies and where then eventually made into immortal deities. (In the earliest Christian theologies this is a direct parallel to Jesus who was not originally a part of any “trinity.”)

Deity in the flesh. Pagan myth is full of gods that could be seen, touched, and heard. My favorite is Dionysus who spent a lot of time walking around the Mediterranean setting up grape fields and driving those who didn’t worship him literally mad. There are some myths that talk about the god even visiting ancient India. Dionysus and Heracles were both gods that “did stuff” in human bodies and where then eventually made into immortal deities. (In the earliest Christian theologies this is a direct parallel to Jesus who was not originally a part of any “trinity.”)

Gods who resided in the heavens also came back to Earth in human form as well. One of the best known tales of this sort can be found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and involves the gods Jupiter and Mercury (Zeus and Hermes). The gods descend to Earth disguised as mortals and ask every house they visit for a meal and a place to sleep; thousand of doors are slammed in their faces. Eventually they stop at the home of the couple Philemon and Baucis, who are poor but welcoming. The gods of course bless the couple and eventually grant them their wish to “die together.” (The gods also destroy the homes of those that refused them a meal, lots of parallels to Yahweh here.) At the moment of their simultaneous death the couple are transformed into two trees sharing one trunk, together forever. Ovid ends his tale with “They now are gods, who served the Gods; To them who worship gave is worship given.” (2)

Miraculous conceptions. As I wrote earlier pagan gods were not born of virgins, but that doesn’t mean their conceptions were any less fabulous. Just because the Christian conception of Yahweh made sex “icky” doesn’t mean there aren’t parallels. The writers of Matthew and Luke write of Jesus’s conception in the following fashion:

This is how the birth of Jesus the Messiah came about[d]: His mother Mary was pledged to be married to Joseph, but before they came together, she was found to be pregnant through the Holy Spirit. (Matthew 1:18)

The angel said to her, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born[d] will be holy; he will be called Son of God. (Luke 1:35)

Both quotes taken from the New Revised Standard Edition of The Bible

The passage in Luke is especially telling. “The Holy Spirit will come upon you” is not that far off from how Zeus visited several young women. The child Perseus was born after Zeus visited Danae as a “golden rain.” The only difference between a golden rain and the Holy Spirit is that Zeus certainly enjoyed his visit a little bit more. Many myths tell of how humans were incapable of directly looking into the face of a god, so the gods had to transform themselves in order to have sex with mortals. Figures from myth weren’t the only children of Zeus either, famous historical personages were also said to be born of unions between gods and mortals. In some histories the father of Alexander the Great is said to be Zeus himself.

The passage in Luke is especially telling. “The Holy Spirit will come upon you” is not that far off from how Zeus visited several young women. The child Perseus was born after Zeus visited Danae as a “golden rain.” The only difference between a golden rain and the Holy Spirit is that Zeus certainly enjoyed his visit a little bit more. Many myths tell of how humans were incapable of directly looking into the face of a god, so the gods had to transform themselves in order to have sex with mortals. Figures from myth weren’t the only children of Zeus either, famous historical personages were also said to be born of unions between gods and mortals. In some histories the father of Alexander the Great is said to be Zeus himself.

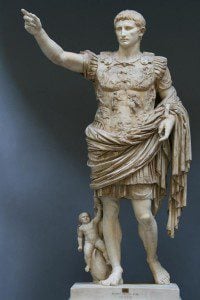

The Roman Emperors as gods. I’ve had Christians tell me that there is only one person in history ever referred to as the “son of god.” Figures like Heracles were always called “son of Zeus” they tell me. That’s true, most gods were identified specifically by their parents, but it’s not true that Jesus was the only person referred to as “son of god,” and he probably wasn’t even the first. That honor belongs to Octavian (63 BCE to 14 CE), Caesar Augustus, who was first hailed as the “Son of God” as early 40 BCE, before he was even emperor. As the adopted son of the deified Julius Caesar it made sense for Augustus to be considered a god, but he was also said to have been the son of Apollo, born ten months after his mother had a tryst with the god in the form of a snake. (3)

Much like the Jesus, Roman Emperors were seen as both divine and human figures. Truly great Emperors, such as Octavian, were sometimes worshipped during their lifetimes (a thing Octavian was not comfortable with), but most emperors became deities after they had died, by a vote of the Roman Senate. Bad emperors were often denied the status of godhood, but good emperors generally received it. If your predecessor was a god, wouldn’t it make sense that you too were a god in some sort of sense? Going from human emperor to god wasn’t just a “status” thing either, deceased emperors really were worshipped as gods, though gods very low in the hierarchy of deity. (4) That the development of Jesus as “God” ran concurrently with the rise of the Roman Emperors as gods cannot be just a coincidence.

Much like the Jesus, Roman Emperors were seen as both divine and human figures. Truly great Emperors, such as Octavian, were sometimes worshipped during their lifetimes (a thing Octavian was not comfortable with), but most emperors became deities after they had died, by a vote of the Roman Senate. Bad emperors were often denied the status of godhood, but good emperors generally received it. If your predecessor was a god, wouldn’t it make sense that you too were a god in some sort of sense? Going from human emperor to god wasn’t just a “status” thing either, deceased emperors really were worshipped as gods, though gods very low in the hierarchy of deity. (4) That the development of Jesus as “God” ran concurrently with the rise of the Roman Emperors as gods cannot be just a coincidence.

The Logos or Word. The most mystical and theological of the four gospels in the New Testament is the Book of John, the latest of the four (written between the years 90 and 100 CE) and it has clearly been influenced by (pagan) Platonic philosophy. At the start of his book the author of John writes:

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being.” John 1:1-3 from the New Revised Standard Version

In Platonic philosophy there are two realities. One of those realities was spiritual and the other physical. Deity is seen as spiritual, and that “pure spirit” is unable to have direct contact with the physical. In order to have contact with the world of matter the spiritual needs an intermediary, in Platonic theory that go-between is the Logos, the Greek word for word. In addition to being the intermediary between the two realms, the Logos is something that also exists within ourselves. It’s the little bit that helps us connect to the divine, the realm of spirit. (5)

In Platonic philosophy there are two realities. One of those realities was spiritual and the other physical. Deity is seen as spiritual, and that “pure spirit” is unable to have direct contact with the physical. In order to have contact with the world of matter the spiritual needs an intermediary, in Platonic theory that go-between is the Logos, the Greek word for word. In addition to being the intermediary between the two realms, the Logos is something that also exists within ourselves. It’s the little bit that helps us connect to the divine, the realm of spirit. (5)

In this particular case, Jesus is the Logos (Word) because it’s the only way for a much higher god to interact with humanity. Yahweh can’t possibly visit Earth, so he must send another entity. In religious scholar speak the Logos is a hypostasis, a part of Yahweh, yet also distinct from him. (Wisdom written about in Proverbs Chapter 8, “Does not Wisdom call out? Does not understanding raise her voice?” is another hypostasis.) Ultimately this type of thinking would be referred to as Neo-Platonism, but the author of John was writing before Neo-Platonism became an established school of thought. Both Christian and Jewish schools of thought were influenced by Plato, again proving that no religion arises in vacuum and that no religion ever completely escapes the philosophies and cultures that surround it.

(I have often remarked that we Pagans sometimes spend more time talking, processing, and belittling Christianity than we do discussing “Pagan things.” Because of that I had reservations when I began writing this article, but I think the majority of this article is about Paganism. There’s Frazer in here, lots of mythology, and it’s certainly not an attempt to belittle Jesus. If you disagree feel free to let me have it.)

Notes

1. That quote comes from the second edition of the Encyclopedia of Religion and the article Dying and Rising Gods by Jonathan Z. Smith. I first came across the quote in Did Jesus Exist by Bart Ehrman (Harper Collins, 2012) on page 227. I was influenced directly by Smith in the writing of this article due to his book Drudgery Divine.

2. How Jesus Became God by Bart Ehrman, Harper Collins Publishers, 2014. Pages 19 and 20 I’m a big fan of Ehrman, one of the most easily digestible of modern scholars on the subject of Jesus. Sometimes his books are a bit too simplistic for me, but few writers have done a better job articulating the origins of the New Testament and the history of Jesus.

3. How Jesus Became God pages 29 and 30

4. How Jesus Became God page 32

5. How Jesus Became God pages 74-75