Fakelore is a word often used to dismiss “made up” folklore or history. If it sounds insulting or condescending, well, I think that’s the point. Instead of using fakelore to describe some of Modern Paganism’s more controversial (and historically dubious) origin stories I prefer to think of them as what they are: mythology. Even if these stories aren’t always accurate in the details, they do often express universal truths. There are things that can be learned by examining the ideas behind Matriarchal Pre-history, the Burning Times, and the Modern Witchcraft Revival.

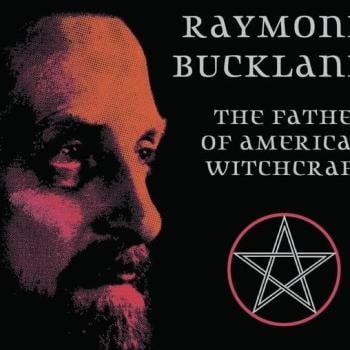

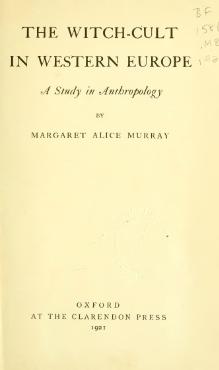

Often forgotten in the discussions about these myths is that they weren’t created to intentionally deceive anyone. Scholars created many of them, and blessed others either directly or indirectly. Dr. Margaret Murray, author of The Witch-Cult in Western Europe not only believed in Witchcraft as an organized religion in direct opposition to Christianity during the Middle Ages, she believed it had survived into the present day! One aspect of fakelore is that it’s often designed to directly profit the individuals who create it. That’s not the case with the founding myths of 20th Century Paganism.

The phrase The Burning Times was first used by English-Witch Gerald Gardner in his 1954 book Witchcraft Today. He used it in reference to the Witch Trials of of the Early Modern Period, which just so happened to be the period written about in Murray’s Witch-Cult in Western Europe. (I always want to place the Witch Trails and the Burning Times in the Middle Ages, sometimes the Renaissance, but they were a rather late development.) The phrase is both tragic and poetic and it’s not surprising that it connected with a wide range of people. The story of the Burning Times peaked in the 1970’s, in large part due to Second-Wave Feminism. In 1981 Charlie Murphy’s The Burning Times immortalized the myth and phrase in song, placing it firmly in the Modern Pagan landscape. (It’s also a beautiful and powerful retelling of the story.)

The Myth: It’s hard to summarize the Burning Times story into just a few paragraphs. The phrase obviously refers to the deaths (often by burning) of women and men accused of witchcraft, but there are other nuances to it. Generally the witches put to death were thought to be a part of an organized religion that existed in opposition to Christianity, a religion that generally had a Goddess as its central figure. That the people executed during the Witch Trials were Witches just like (possibly) you and (most certainly) I is one of the things that makes the story so potent. In many versions of the story the victims were overwhelmingly women (an actual truth in some places that I’ll examine below).

The most common telling of the story comes not from a a Pagan group but a political one. The New York group WITCH popularized the version of the Burning Times most familiar to many of us. Ronald Hutton summarizes their version of the tale in his book Triumph of the Moon (1999):

“WITCH (Women’s International Conspiracy From Hell) was formed in New York, with a manifesto which stated that witchcraft had been the religion of all Europe before Christianity and of European peasants for centuries after. Its persecution in the early modern period had therefore been the suppression of an alternative culture by the ruling elite, but also a war against feminism, for the religion had been served by the most courageous, aggressive, independent, and sexually liberated women in the populace. Nine million of these had been put to death. To gain freedom, therefore, modern women needed to become witches again, and could do so simply ‘by being female, untamed, angry, joyous, and immortal.'” -Ronald Hutton, Triumph of the Moon pg. 341

More or less that’s the story I grew up with in the early 90’s, and one I still hear repeated on occasion. Not all of the telling is literally true, but I still think it has value.

The Truth: Without question the Burning Times were a very real thing. The Witch Trials we are most familiar with began in the 1400’s and lasted until the 1700’s, a period of about 350 years*. During that timeframe tens of thousands of people were executed for witchcraft. Conservative (and the most common) estimates by scholars place the number between 40 and 50,000 but I’ve also seen estimates on the higher-end of 80,000 or so. That’s a far cry from the nine million number cited above, but also big enough to be significant. Accusations of Witchcraft in Europe, the British Isles, and the Americas weren’t necessarily isolated they appeared with some frequency. In addition not everyone charged with Witchcraft was executed.

So where does the nine million number come from? Mostly from a German historian named Gottfried Christian Voigt who came up with it after:

“discovering records of the burning of thirty witches at Quedlinburg (his home town) itself between 1569 and 1583 and assuming that these were normative for every equivalent period of time as long as the laws against witchcraft were in operation.”-Ronald Hutton Witches, Druids, and King Arthur pg. 30″

The idea of Witchcraft as an organized religion during that same period is usually attributed to Margaret Murray, but the person probably most responsible for spreading the idea was Frenchman Jules Michelet. Michelet’s La Sorcière (1862, translated and published in English in 1899) suggested that the victims of the Witch Trials were part of a somewhat organized Pagan religion generally found in the more rural areas of France. Michelet paints both the nobility and the Catholic Church as the bad guy in La Sorcière, which is not surprising since he was disgusted by both institutions. (It’s also worth mentioning that French peasants tended to be the most pious Christians, it’s the nobility that liked to play with high-magic and other taboo things.) La Sorcière didn’t have much of an impact in France (where it was mostly dismissed, besides Michelet wrote his book as a cash-in not as a serious academic study) but it’s ideas did become popular in the English speaking world.

Most certainly Murray was influenced by Michelet, the difference between La Sorcière and Murray’s The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) was that Murray took the theory seriously. Witch-Cult contains actual research and trial records directly from the Witch Trails. Some of it is taken out of context and isolated ideas are said to represent wide expanses of Europe, but at least she makes a convincing argument. Witch-Cult was dismissed by most scholars who had actually studied the period in question upon its release, but others with less knowledge of the Witch Trials bought into her argument. More importantly much of the public (especially after World War II) latched onto Murray’s ideas. Even after her work had been dismissed by a majority of scholars it was still Murray and what became known as The Murray Thesis in the Encyclopedia Brittanica’s entry on Witchcraft (right up until 1969, a period of about forty years).

The prominent deity in Murray’s Witch-cult was a corrupted form of the Horned God worshipped as the Christian Devil, this made it very different from the Goddess-centered mythology of the Burning Times. Linking Murray’s Witch-cult to the Triple Goddess as Maiden, Mother, and Crone has a certain poetic beauty, but is completely unsupported by Murray’s own works. Like most myths, the story of the Burning Times evolved from a variety of sources.

The prominent deity in Murray’s Witch-cult was a corrupted form of the Horned God worshipped as the Christian Devil, this made it very different from the Goddess-centered mythology of the Burning Times. Linking Murray’s Witch-cult to the Triple Goddess as Maiden, Mother, and Crone has a certain poetic beauty, but is completely unsupported by Murray’s own works. Like most myths, the story of the Burning Times evolved from a variety of sources.

One thing that the Burning Times myth accurately portrays are the victims of its brutality: women. Most victims of the Witch Trials were women, perhaps as many as 75 to 80%. This did vary across Europe (in some places men were more likely to be accused by a significant margin) but was the general norm. Women accused of witchcraft tended to be older and unmarried. The lower someone’s social status the more likely they were to be thought of as a witch. It was far easier to point the finger at the old lady at the edge of town than a respected member of society.

The idea that the Witch Hunts specifically targeted midwives and cunning-folk is harder to quantify. Certainly there were midwives and cunning-folk who were executed, but they were not a majority of victims. Cunning-folk were never completely loved by the Christian Church(es) but they also didn’t exist on the far margins of society. Also much of their spell-work was used to fight off witches. I certainly identify with cunning-folk but they didn’t self-identify as witches, especially during the Burning Times period. (It’s hard to imagine anyone self identifying as a witch during the period we call the Burning Times.)

Were there people we might identify as Pagans executed during the Burning Times? I have trouble with this question because it gets to the heart of “what’s a Pagan?” Do I think there was an organized-continent-wide Witch-religion during the Witch Trials? No, that’s just not supported by any real evidence. I do however believe that certain paganish beliefs might have existed in isolation, or perhaps were re-adopted.

Author’s Note: There are Pagans (and others) out there who are going to object to this rather conservative accounting of history. There are lots of smart people who believe that there were real, identifiable witches who died during the Burning Times and that the numbers were much higher than 50 or even 80 thousand. For an alternative take on witchcraft during the Burning Times check out the works of Emma Wilby, and the website of Max Dashu.

The Renaissance is full of imagery saluting the gods of antiquity, I find it easy to imagine someone choosing to honor them because of it. Magical beliefs are easily passed down, and some magical beliefs have survived since pagan antiquity. They were almost always re-adapted to fit into a Christian context, but they did continue to exist. If someone wants to see the Italian benandanti as Pagan I certainly understand the impulse. However it doesn’t prove that everyone executed during the Burning Times was a witch or magical person.

Ultimately people were executed for witchcraft due to a number of factors. Sometimes it was economic, or perhaps political. It could be personal, or just a reaction to unexplained and uncontrollable events. “Witches” were often scapegoats, and it’s important to remember that this period of history was one of rather rapid social change. They started before Columbus “sailed the ocean blue” in 1492 and ended shortly before the founding of the United States. I’d say that’s a lot of change in a short period of time.

This is an extremely long article but I feel as if I would be remiss if I didn’t address perhaps the most memorable scene from Burning Times mythology. Charlie Murphy immortalized it in his previously mentioned song whit this verse: And the tale is told of those, who by the hundreds, Holding together chose their death in the sea, While chanting the praises of the Mother Goddess, A refusal of betrayal, women were dying to be free. It’s a powerful image and I remember it washing over me the first time I heard it. However the legend itself is a rather dubious piece of scholarship, Ronald Hutton elaborates:

” . . . feminist writers were drawing upon an existing body of information and interpretation, and responding to wider cultural patterns. Ocassionally they would engage in some wanton invention upon their own part. The outstanding example of this . . . . commenced with with a passage in a nineteenth-century work on epidemic disease, which dealt with outbreaks of hysteria in southern Italy between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, attributed to the bite of a tarantula spider. One aspect of this hysteria was an acute longing for water, and the text reported that sufferers would sometimes themselves into the sea to assuage it. It appended an Itlian song which purported to express this longing. Two decades later after the publication of this passage . . . . Lecky incorporated it into his history of European morality, beneath the comment that comment that in the same period accused witches were often said to commit suicide in prison. (Mary) Daly put Lecky’s two pieces of material together, to produce a lurid fantasy of mass suicides of witches who, fearing arrest, torture, and execution, preferred to walk into the sea together and drown. It became one of the most compelling images of an episode of history and pseudo-history for which American feminism was now starting to employ Gerald Gardner’s emotive name, ‘The Burning Times.'” -Ronald Hutton, Triumph of the Moon, page 344.

Why the Burning Times Matter: Dismissing the Burning Times as fakelore doesn’t work, because there was a Burning Times. It didn’t feature the deaths of millions, but thousands died needlessly, and many more were punished and lived in fear because of it. Calling their deaths fakelore is insulting and further marginalizes the horror they were put through.

Were they all witches? No, but they were human beings. If you can’t relate to the innocent and powerless being executed (and tortured) there’s something wrong with you. I certainly don’t see any harm relating to these people as my magical kin. If not for time and circumstances those executed could very well have been my mother, my wife, or the sisters in my Craft I hold most dear. Honoring them certainly isn’t appropriation (and besides, isn’t it about time somebody did?)

If there’s one thing that stays with me about the Burning Times it’s the idea of be vigilant. Society loves to pick on those who stand at the outskirts of it. As a Witch I identify with that. I can walk in the mundane world, but I’m not of it. My place is with those on the margins. And what could be more provocative than calling one’s self a Witch and thumbing your nose at our broken, patriarchal society?

The Burning Times continue too, in places like Africa, and sometimes even makes its way back into the Western World. Where superstition and fear rule there will be people accused of witchcraft and they will die because of it. Our world won’t be truly free of The Burning Times until everyone is allowed to be who they are and live the kind of life they choose to. That’s a lesson we should not, and I will not, forget.

*It should be pointed out that people are still being murdered over “witchcraft” in various parts of the world. The Burning Times aren’t over, they’ve just shifted locations.